Dehumanization and the Myth of Moral Disengagement

For decades researchers have claimed that dehumanization promotes moral disengagement, but the facts tell a very different story

It is often claimed that the function of dehumanization is to promote moral disengagement. This thesis was introduced into the psychological literature in the 1975 in a paper by Bandura, Underwood, and Fromson titled “Disinhibition of aggression through diffusion of responsibility and dehumanization of victims,” and has stuck ever since. It has also spread beyond social psychology into other fields. For instance, in sociologist Helen Fine’s influential formulation, dehumanized people are excluded from “the universe of moral obligation.” And although she never mentions dehumanization explicitly, Hannah Arendt’s notion of the banality of evil.

The general idea is that dehumanized people are placed outside the sphere where moral considerations apply. And because morality is irrelevant to the treatment of dehumanized people, it is permissible to treat them in whatever way one likes. They can be exploited, abused, and even exterminated without compunction.

The idea that dehumanization serves to morally distance dehumanizers from those whom they dehumanize is wrong. It’s not just a little bit wrong. It’s wrong in a very major, very serious way. It is so wrong that, in my opinion, one cannot understand the most lethal forms of dehumanization—the kind that leads to genocide and mass atrocity—as long as one holds onto the moral disengagement thesis. This is because far from being morally disengaged, dehumanizers are obsessively engaged with the moral status of their victims.

There are very many examples demonstrating the hyper-moral focus of dehumanizers, their obsessive concern with the depravity and dangerousness of their victims, and the extremes of retributive violence that they inflicted on them. I document and discuss many such examples in my books On Inhumanity: Dehumanization and How to Resist it (Oxford University Press, 2020) and Making Monsters: The Uncanny Power of Dehumanization (Harvard University Press, 2021). In this essay, I will focus on just one: the lynching of Ell Persons in 1917.

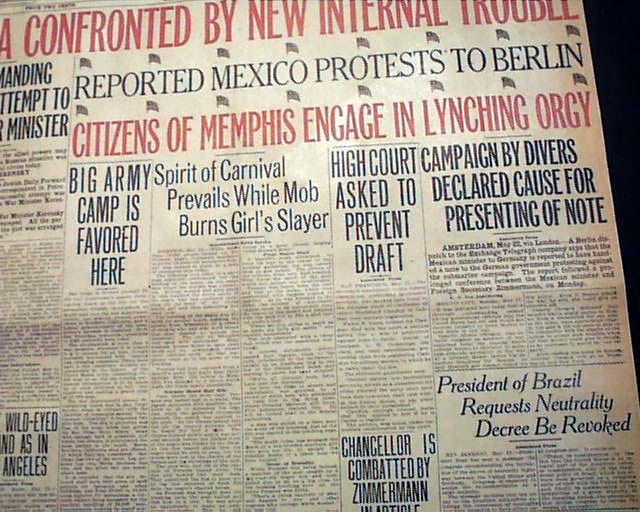

Scroll back to the beginning of this essay and you’ll see a page from the San Diego Evening Tribune dated May 22, 1917. The red-letter headline “Citizens of Memphis engage in lynching orgy,” refers to the torture and murder of an African American man. Further down the page, a caption reads“Spirit of carnival prevails while mob burns girl’s slayer” with an article describing the lynching just below.

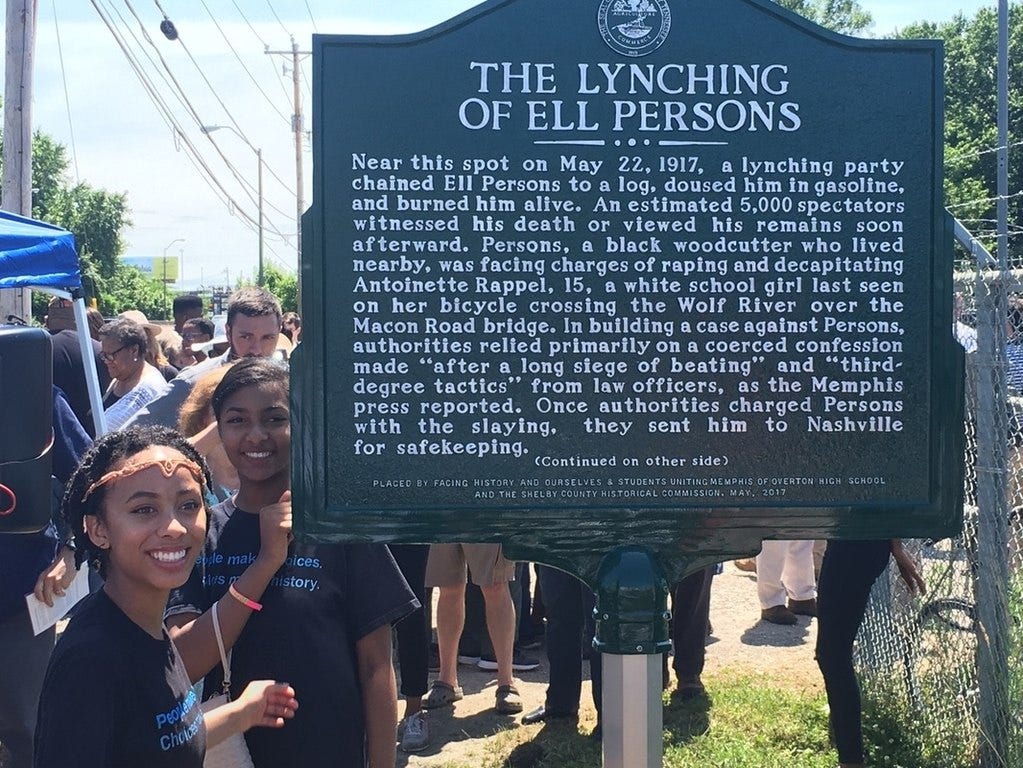

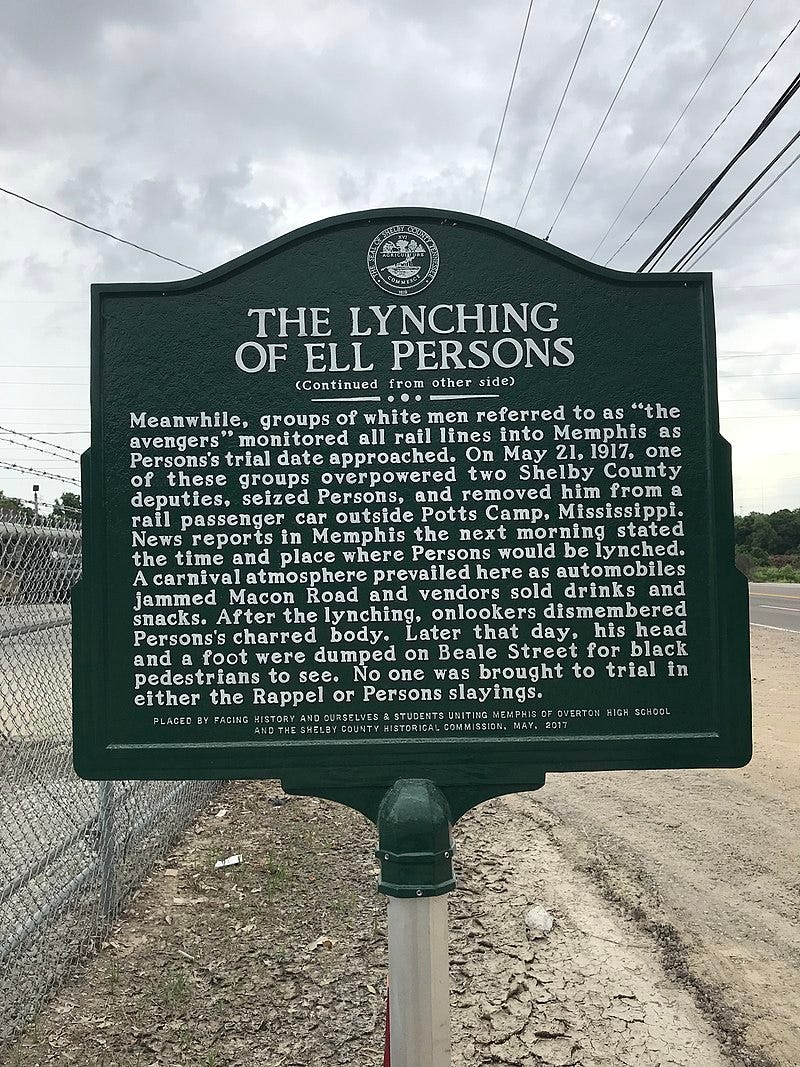

Ell Persons, a local woodcutter, was accused of murdering Antoinette Rappel, a fifteen-year-old White girl whose beheaded body was discovered just south of Memphis city limits. The physician who examined the corpse said she had been sexually violated.

Persons lived near where the body was discovered. Despite evidence that an unidentified White man—a stranger—was the likely culprit, Persons was questioned three times by the police and was then arrested. He allegedly confessed to the crime (under torture), and was handed over to the White mob seeking vengeance. Philip Dray describes the subsequent course of events, in his book At the Hands of Persons Unknown: They Lynching of Black America:

The next morning’s papers announced the intention of the mob to lynch Persons at the scene of the crime. Scores of men, women, and children had been camped out at the site for more than twenty-four hours, and the press coverage brought still more, some parents sending notes to school, asking that their children be excused to attend. “Conspicuous among the mob were several vendors of sandwiches and chewing gum,” noted a reporter who mingled with a crowd that he estimated at three thousand.

Dray’s account, extracted from contemporary sources, confirms the Tribune’s claim that there was a carnival atmosphere. But this atmosphere abruptly changed once the lynching got under way. As Dray recounts, a Master of Ceremonies raised his hand, bidding the five thousand strong crowd to fall silent. Then, looking out on the sea of White faces, the murdered child’s mother spoke:

“I want to thank all of my friends who worked so hard on my behalf,” she said, then added, to a roar of approval from the crowd: “Let the Negro suffer as my little girl suffered, only ten times worse” …. “We’ll burn him!” someone yelled back…. “Burn him!” screamed a woman, “And burn him slow!”

Persons was then doused with gasoline and set alight. Two men stepped up to slice off his ears. Others cut off his nose and lower lip. Spectators complained that too much gasoline was used, causing him to die quickly rather than slowly by degrees. Then, once he was dead….

Persons’ corpse soon cooled sufficiently to be dismembered. His head…was driven in an automobile to the corner of Rayburn Boulevard and Beale Street in downtown Memphis, where whites flung it onto the sidewalk at the feet of a group of black pedestrians, shouting “Take this with our complements.” Photographs of the head, with ears, nose, and lower lips severed, were available for twenty-five cents throughout Memphis, and the head itself was briefly displayed in a barbershop….

This description does not suggest that the perpetrators and spectators were disengaged. Far from it. They were emotionally engaged, but were they morally engaged? I think that the only reasonable answer is “Yes.”

Notwithstanding the festive atmosphere that often prevailed at large public lynchings, the torture, mutilation, and extrajudicial execution of African Americans should not be thought of a simply a sadistic form of entertainment. As is evident from this example, as well as many others, these atrocities were fueled by a kind of moral fury. The victim was seen as an embodiment of evil, for whom no form of punishment was too severe—a moral status that encompassed virtually all Black men in the Jim Crow South. Black men were characterized as monsters, rampaging rapists, pedophiles, and murderers. This explains why their persecutors could throw evidential considerations to the wind so casually. If these people are by their very nature monsters, then evidence of criminal acts become irrelevant. Even if Persons didn’t kill Rappel, he had it in him to do so, and that was good enough for the policers of the color line.

Harvard University sociologist Orlando Patterson underscores the moral/religious overtones of spectacle lynchings (public lynchings before an audience of hundreds or thousands of spectators). He writes in his brilliant essay “Rituals of blood” that “There is no denying the profound religious significance that these sacrificial murders had for Southerners.” Often, Christian clergymen played a prominent role, and justified the lynching on Biblical grounds. For example, Patterson discusses that on the occasion of the 1903 lynching of George White in Wilmington, Delaware, the Reverend Robert Elwood took as his text Corinthians 5:13—“Therefore put away from ourselves that wicked person.” The lynchers followed Elwood’s advice: “Following the sermon, a mob of several thousand people stormed the jail, overpowered the guards, and ‘dragged the prisoner to a selected site…and there burned him alive.’” Furthermore, Patterson notes, “Sunday was a favorite day for lynching” and “Although not the most popular sites, churchyards were often used for lynching, and it was not uncommon to burn Afro-American churches before and after sacrificial lynching.”

Spiritually, the degenerate, masterless slave who dared to assert his manhood or freedom became the ideal sacrificial victim. As ex-slave, he symbolized the human wickedness and sin that haunted the fundamentalist souls of his executioners. And as “black beast” he could be horribly sacrificed, without any sense of guilt, to a wrathful, vengeful God as a prime offering of blood and human flesh and as the soul of his enemy, Satan.

Was Ell Persons dehumanized?

In light of the overwhelming evidence that Black people—especially Black males—were dehumanized by White Americans in the Jim Crow South, this is really a non-question. Thousands of Black men suffered at the hands of White lynch mobs like Ell Persons did and were dehumanized by Southern Whites (for details, see my book Making Monsters). We can safely assume, then, that many members of the throng gathered together to watch the horrors inflicted upon Ell Persons that day regarded him as less than human, not a person, but a bloodthirsty brute in human form.

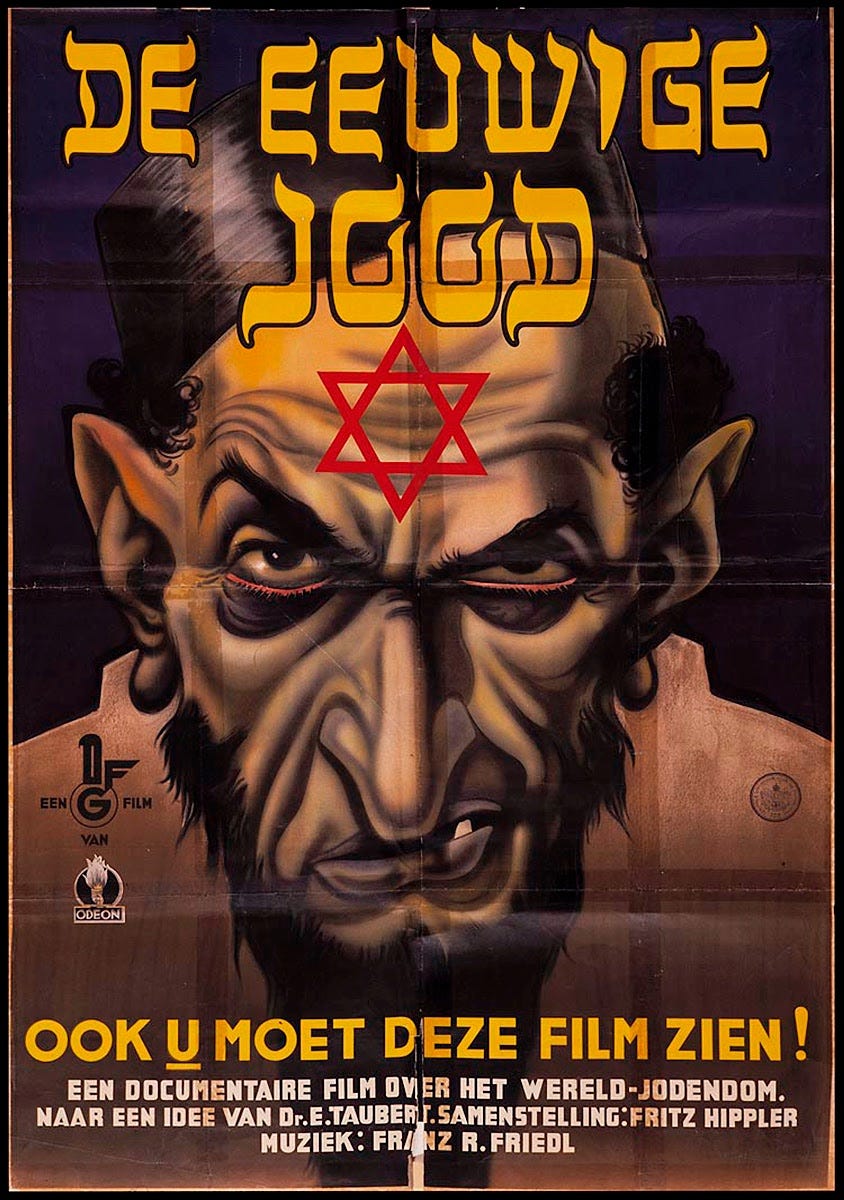

Dehumanizers’ intense moral engagement with those whom they dehumanize is not limited to the dehumanization of African Americans. It is a common, perhaps even universal, feature of the dehumanizing process. We find it in the Holocaust, when Jewish people were demonized as evil entities that deserved to be exterminated, and virtually any eruption of genocidal in which dehumanization has played a key role.