On Saturday, September 4, Donald Trump gave a typically lengthy, rambling speech to a packed MAGA crowd in Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania. Its ostensible purpose was to galvanize support for Mehmet Oz for congress and Doug Mastriano for governor. But there was more to it than that. Thrust of his speech was, in effect, an announcement of his candidacy for the 2024 election, and it left us in no doubt about what a Trump regime redux would look like.

Joe Biden made waves two days previously when he referred to the MAGA ideology as “semi-Fascist.” But there was nothing “semi” about the fascist rhetoric on display in Wilkes-Barre.

I have been tracking Trump since the moment in 2015 that he descended the golden escalator to announce that he was throwing his hat into the Republican ring. Listening to that speech, I grew increasingly alarmed. I recognized that far from being a clown, as many of my friends and colleagues seemed to think, this was a dangerous man whose speech could have been lifted straight out of Dr. Goebbels’ playbook. His most recent speech is in many respects a reprise of the one he gave in 2015—but this time the fascism is even mode blatant, and the dehumanization more explicit.

To flesh this out, I need to talk about Germany in 1932. The Nazi party was formed in 1920 as a right-wing fringe group in the politically chaotic aftermath of the First World War, but it never managed gain much of an electoral foothold until the great depression ravaged the German economy. In 1932, German voters chose to make the Nazis the major players in the Reichstag, setting the stage for Hitler to subvert the rule of law and don the mantle of Führer the following year.

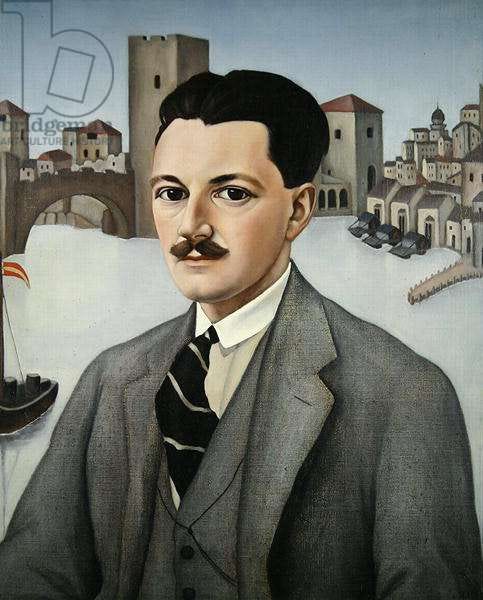

Hitler campaigned furiously that year, flying around Germany in an airplane to rally his base. An Englishman named Roger Money-Kyrle was a spectator at several of these events. Money-Kyrle was an interesting thinker. He was a psychoanalyst with two PhDs—one in philosophy (supervised in Vienna by Moritz Schlick) and the other in anthropology—who was keenly interested in using psychoanalysis to make sense of social and political phenomena. He shared his observations of Hitler and Goebbels’ performances in a 1941 paper titled “The psychology of propaganda.” He wrote:

It was not easy to keep one’s balance; for if one was unable to identify oneself with the crowd and share its intense emotions, one almost inevitably personified it as a sinister and rather terrifying super-individual…. The people seemed gradually to lose their individuality and to become fused into a not very intelligent but immensely powerful monster….Yet there was something mechanical about it too; for it was under the complete control of the figure on the rostrum. He evoked or changed its passions as easily as if they had been the notes of some gigantic organ.

The tune that Hitler and Goebbels played on that organ was “very loud, but very simple.”

For ten minutes we heard of the sufferings of Germany…since the war. The monster seemed to indulge in an orgy of self-pity. Then for the next ten minutes came the most terrific fulminations against Jews and Social-democrats as the sole authors of these sufferings. Self-pity gave place to hate; and the monster seemed on the point of becoming …. But self-pity and hatred were not enough. It was also necessary to drive out fear, which might otherwise have made the Party too cautious to defy the State. So the speakers turned from vituperation to self-praise. From small beginnings the Party had grown invincible. Each listener felt a part of its omnipotence within himself. He was transported into a new psychosis. The induced melancholia passed into paranoia, and the paranoia into megalomania.

Trump’s 2015 speech followed this formula to the letter. He began by painting a picture of the United States as the exploited laughing-stock of the world, moved from there to inducing paranoia with his comment about rapists and murderers from Mexico and the Middle East, and peaked with the megalomaniac vision that he, Donald Trump, is the one man who can save America and make it great again. Journalist Gwynn Guilford, who attended several of Trump’s rallies, found that “in the many reams of observations I scribbled down reflecting on the Trump rallies. Nearly every paragraph fit Money-Kyrle’s sequence.”

Trump’s Wilkes-Barre speech conforms to the same rhetorical template. He began by inducing a sense of victimization and despair. “Our country is going to hell,” he intoned, “skyrocketing inflation, ramping crime, soaring murders, crushing gas prices, millions and millions of illegal aliens pouring across our border, race and gender indoctrination converting our schools….” But this time, the enemy is within rather than without. Joe Biden, and the unnamed, malevolent puppeteers that pull his strings are “enemies of the state.”

Trump went further than ever before in representing his opponents as embodiments of metaphysical evil, remarking that when Biden made his recent speech, he had “red lighting behind him, like the devil” (an image bound to strike a chord for the evangelical faithful) and that “the FBI and Justice Department have become vicious monsters.” And in a move beloved by old-time Nazis, he accused these sinister forces of trying to silence him and his followers.

They're trying to silence me and more importantly, they are trying to silence you. But we will not be silenced, right. We will never stop speaking the truth. We have no choice because we're not going to have a country love. The evil and malice of this demented persecution of you and me should be obvious to all entities.

And of course, there was the grandiose, megalomaniac high, that sent a wave of euphoria through the throng: “The MAGA movement is the greatest in the history of our country. And maybe in the history of the world, maybe in the history of the world.”

Trump’s speech was, like all of his speeches, long and repetitive. He revisited all three elements—the depressive victimization, the paranoid terror, and the megalomaniac inflation—several times. The repetition was a feature, not a glitch. As Money-Kyrle remarked of Hitler and Goebbels, “the repetition did not bore the audience, but, like the repetition in Ravel’s Bolero, seemed only to increase the emotional effect.”

Despite their similarities, there is an ominous difference between Trump’s rhetoric in 2015, and his rhetoric today—one that should give us pause. In 2015 he excoriated leaders like Obama and Bush as incompetent, but he stopped short of painting them as enemies of the American people. In 2017 he began to characterize media outlets that did not cover him favorably as “enemies of the people” (a phrase with a long history of use by totalitarian regimes), but this was a far cry from his more recent turn to describing a huge swath of the American people as enemies of America, or as witless lackies of such.

Trump has never been shy about characterizing outsiders as subhuman (recall his comment that undocumented immigrants or gang members are “animals”), but referring to Biden as like Satan and the FBI and Department of Justice as “monsters” is a new and disturbing departure on the road to fascism. These elements, in conjunction with Trump’s hints that he will run for president in 2024 (for example, “I will never turn my back on you. And you will never turn your back on me because we love our nation. And we will save our nation from people who are trying to destroy it”) bode ill for the future. Even if Trump decides not to run, or is defeated, the damage to our nation may be irreparable.

Vital reminder that dehumanization and the words that encode it matter

What is your definition of "fascist"? This is not a challenge, but a student query. The word is so widely used today that it seems to have become a vague synonym for "enemy."