Race, Dehumanization, and Disability

The dehumanization of cognitively disabled people and its relationship with racial dehumanization

My work on dehumanization over the past sixteen years emphasizes the powerful connection between race and dehumanization. Groups of people who are dehumanized are very often first racialized. When people are racialized, they are regarded as lesser, inferior humans. Dehumanization takes this denigration further. Rather than being regarded merely as lesser human, they are seen by their persecutors as less than human. That’s why I often call dehumanization “racism on steroids.”

But racialization is not the only precondition for dehumanization. Disabled people, especially cognitively disabled people, have also often been regarded as subhuman entities. This is quite blatant in the Nazi “euthanasia” program, called Aktion T4, which took at least seventy thousand lives, as many as eight thousand of whom were children, between 1939 and 1941, when it was ostensibly—but only merely ostensibly—discontinued. By the end of the war as many as three hundred thousand disabled people had been killed by Nazi physicians,

Nazi doctors described cognitively disabled people as mere “shells” of human beings—creatures that seemed human but were not truly human. This way of thinking did not begin with the Nazis. It was prevalent long before then, as is evidenced by nineteenth century medical literature. For example, the American physician Samuel Gridley Howe described disabled people as “breathing masses of flesh, fashioned in the shape of men, but shorn of all other human attributes…mere organisms, masses of flesh and bone in human shape” nearly a century before Hitler came to power.

When people are racially dehumanized, they are thought of as being subhuman creatures on the inside—as apes, vermin, bloodthirsty predators, and so on. In contrast, when cognitively disabled people are dehumanized, they are represented as having nothing on the inside—as fleshy automatons. In an interview pediatrician Werner Catel, the major instigator of the Nazis’ program of murdering disabled children, Catel described these children as “monsters…nothing but a massa carnis” (“lumps of flesh”) an expression used centuries earlier by Martin Luther to describe a disabled child. “We are not talking about humans here,” he said in the 1964 interview in Der Spiegel, “but rather about beings…that will never themselves become humans endowed with reason and a soul.”

I argue in my book Making Monsters: The Uncanny Power of Dehumanization that racial dehumanization often transforms people into monsters in the eyes of their dehumanizers. Racially dehumanized people are felt to be unnatural, uncanny, disturbing, and also physically threatening. They seem to be both human (on the outside) and subhuman (on the inside), and are cast as violent aggressors (murderers, rapists, terrorists, and the like). But when disabled people are dehumanized, something different happens in the minds of their dehumanizers. They are seen as disturbing and monstrous, but not physically dangerous. Whereas racially dehumanized people—especially males—are typically seen as dangerous superpredators, cognitively disabled people are represented as soulless bodies. This makes acts of violence against them seem morally permissible, like acts of violence committed against robots or inanimate objects. Many of the Nazi doctors, including pediatricians responsible for killing children, were never punished and went on to pursue prestigious medical careers after the war. When pediatrician Wilhelm Bayer was charged in 1945 with crimes against humanity, his defense was that he did not kill human beings. As historian Johann Chapoutot describes, in his book The Law of Blood: Thinking and Acting as a Nazi:

“Such a crime,” he asserted, “can only be committed against people, whereas the living creatures that we were required to treat could not be qualified as ‘human beings.’” Dr. Bayer with great sincerity, kept reiterating that doctors and legal experts had for decades been advising modern governments to shed the weight of useless mouths….These beings were barely human, they asserted, they were corrupted biological elements….

Bayer’s defense succeeded. He and his colleagues were found not guilty.

The atrocities committed against disabled people contrast sharply with atrocities directed at racially dehumanized people. The latter are typically portrayed as acts of self-defense. In Nazi Germany, Jews were regarded as the powerful and relentless enemies of the Aryan race. The battle against the Jews was pictured as a life-and-death struggle against a formidable foe—a battle in which the fate of civilization hung in the balance. In contrast, disabled people were said to be “useless eaters”—subhuman trash that were wastefully consuming resources that should go to feed the able-bodied Volk.

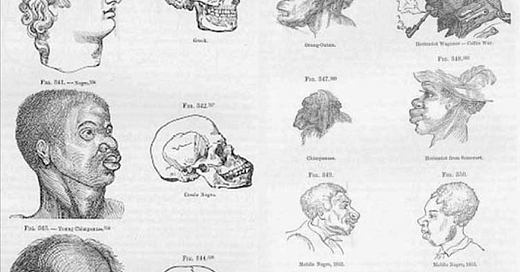

Although the two kinds of dehumanization are strikingly different, there is a surprising connection between them. In racist regimes, race is often regarded as a form of disability. It is a mainstay of Euro-American racial dehumanization of African-Americans are cognitively defective. This was a common eighteenth century notion among Euro-Americans, one embraced by Thomas Jefferson who wrote that Africans are “inferior to whites in the endowments of body and mind.” Nineteenth-century race scientists claimed that Black children’s cranial sutures fuse prematurely, restricting the growth of their brain. The medical scientist Samuel Cartwright—an apologist for slavery—wrote that the underdeveloped brains of Black people accounted for their “indolence and apathy, and why they have chosen, through countless ages, idleness, misery, and barbarian to industry and frugality-why social industry, or associated labor, so essential to all progress in civilization and improvement, has never made any progress among them.” Much the same idea is found in the writings of twentieth century scientific racists like Arthur Jensen, Charles Murray, and their present-day acolytes. Nazis also associated race with disability. According to the testimony of people who worked with him, Josef Mengele regarded Jewishness as an incurable, congenital malady. Mengele’s viewpoint was nested in a deeper tradition of German science, exemplified by the views of the influential biologist Ernst Haeckel, who characterized the so-called lower races as cognitively disabled. Robert Jay Lifton remarks in his book The Nazi Doctors that Haeckel “believed that varied races of mankind are endowed with differing hereditary characteristics not only of color, but more important, of intelligence” and that they are “psychologically nearer to the mammals (apes and dogs) than to civilized Europeans.”

While dehumanization is often described as a pre-reflective, instrumental defense mechanism, even in its more implicit form of social bias or prejudice, this article illustrates that dehumanization is used in defense not only against violence, actual or imagined, but in defense of an in-group's purportedly superior claim to basic human resources such as food, as well as in defense of the current dominant power structures and social hierarchies that allocate such power and resources.