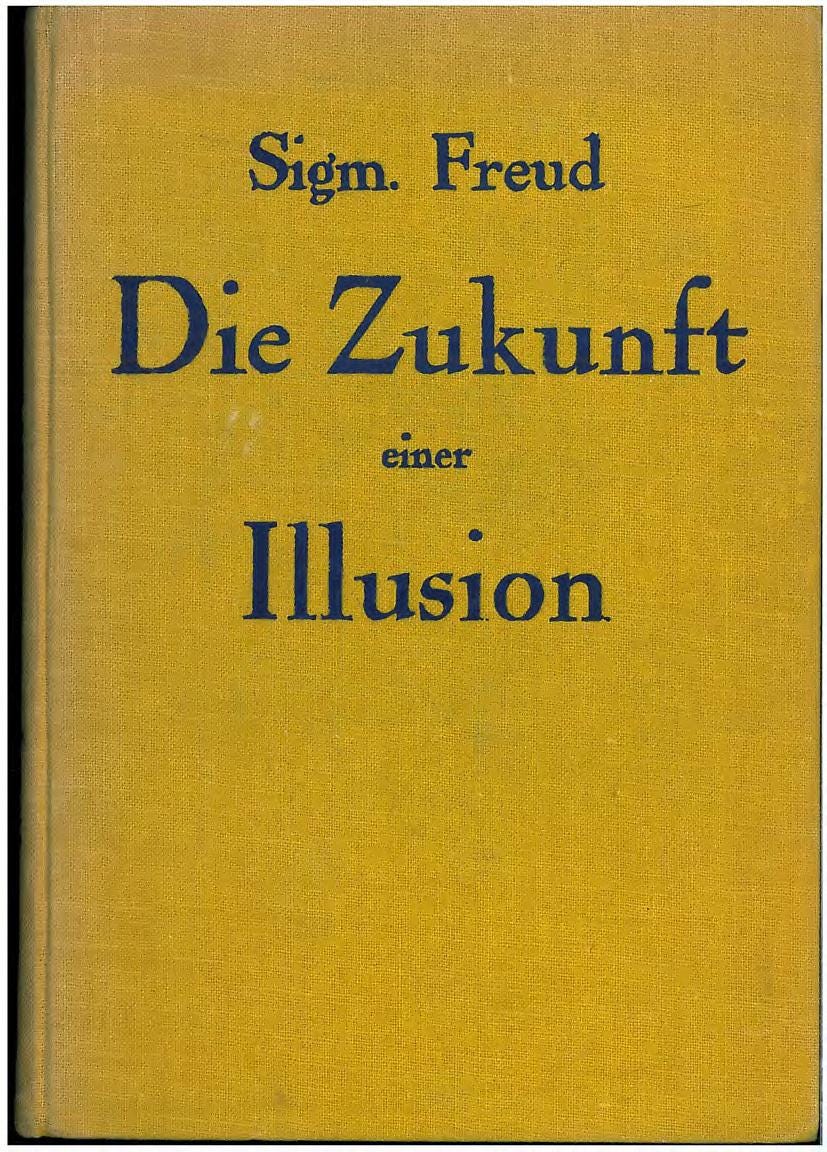

I have found psychoanalytic theory extraordinarily helpful for understanding authoritarian politics in general, and the MAGA phenomenon in particular. There are two texts that I go back to again and again for this purpose. The first is Freud’s 1927 book The Future of an Illusion and the second is Roger Money-Kyrle’s 1941 paper “The psychology of propaganda.” Although they were written a long time ago, these two texts throw light on our current political situation.

Freud’s text might seem like a strange choice, because it is a book about the psychology of religion. But it is actually not strange at all, because authoritarian political movements almost always have powerfully religious overtones. The theological dimension of Trumpism is often explicit in the language of his evangelical followers. For example—just one of many—Republican lawyer Joseph D. McBride tweeted on March 18, “President Trump will be arrested during Lent—a time of suffering and purification for the followers of Jesus Christ. As Christ was crucified, and then rose again on the 3rd day, so too will @realDonaldTrump.” There is even a book titled President Donald J. Trump: The Son of Man—the Christ that seriously argues for Trump’s bona fides as a Christian savior.

It may seem bizarre to those of us who are not MAGA zealots that, in the words of James Risen:

In the upside-down world of the Christian nationalists at the heart of the MAGA subculture, Donald Trump — a porn-star-fucking, Putin-loving, psychopathic liar and traitorous crook who is running for president again just to stay out of jail, grift more dollars, wreak more havoc, and seek further revenge against his enemies — is a Christ-like figure. Of course, they will see him as a martyr straight out of the Bible.

Psychoanalysis helps us to discern the emotionally-driven logic behind what appears to be sheer lunacy. So, let’s first turn to Freud, and see how he can help us make sense of the MAGA faith.

Freud’s target in The Future of An Illusion was the psychology of theism. His project was to address the puzzle of why people believe in the existence of God. The title of the book is important, because Freud used the term “illusion” in a special way. He did not equate illusions with false perceptions or beliefs, as we do in ordinary speech. In Freud’s view, what makes a belief an illusion is not its poor fit with reality. Rather, beliefs are illusions because of their motivation. He defined illusions as beliefs that we hold because we want them to be true, and argued that religious beliefs are illusions in precisely this sense.

Following in the tradition of the German philosophers Ludwig Feuerbach and Karl Marx, Freud held that people believe claims about God and the afterlife because they are comforting. But he also goes further, arguing that religious beliefs are rooted in our awareness of helplessness. Human beings are helpless in the face of injustice—the terrible things that people inflict on one another—and the forces of nature, such as earthquakes, tornadoes, disease, and ultimately death. This sense of helplessness recapitulates what it’s like to be a helpless child, dependent on one’s parents for care and protection. This yearning for salvation from the terrors of life induces people to turn to the illusion of a heavenly Father who will rectify injustice and reward believers with eternal life.

The most potent illusions are delusions. Delusions are illusions that are so powerful that they cannot be moved by evidence. Freud thought that religious beliefs are delusions in this sense. They are, he wrote, “fulfillments of the oldest, strongest, and most urgent wishes of mankind. The secret of their strength lies in the strength of these wishes.”

What does this have to do with the attraction of authoritarian politics? Quite a bit. As I’ve already noted, such political movements often have religious elements. The leader offers salvation to his followers, playing on their feelings of vulnerability, and promising them salvation in an earthy paradise. This shouldn’t be surprising. After all, both religion and politics traffic in our deepest and most insistent hopes and fears. But using Freudian theory to illuminate politics brings us face to face to a yawning gap in his analysis. Freud speaks as though religious beliefs arise spontaneously from within the human mind. But they don’t. Religious beliefs are products of indoctrination, often implemented by promises of salvation.

Authoritarian politicians do something similar. Nobody was born a MAGA zealot. Trump (and others like him) had to motivate people to join him. To understand how he did this, we need to turn to the work of another psychoanalyst, an Englishman named Roger Money-Kyle.

Scion of an old, aristocratic family, Money-Kyrle was an airman in the First World War. Shot down over northern France, he went on to study philosophy at Cambridge university. A few years later travelled to Vienna to complete his PhD under the supervision of the renowned philosopher Moritz Schlick and to undergo psychoanalysis with Freud. After returning to England, he acquired a second PhD—this time, in anthropology—and became a practicing psychoanalyst.

In 1932, Money-Kyrle visited Berlin, where he observed Nazi political rallies and listened to speeches by Hitler and Goebbels. He published his reflections in a 1941 article titled “The psychology of propaganda.”

Money-Kyrle argued that Hitler and Goebbels induced a mass delusion in their audience, by magnifying their feelings of helplessness and then offering them salvation. Their first move was make the audience depressed – to get them to feel that circumstances are dire and perhaps hopeless. “For 10 minutes,” he wrote, “we heard of the sufferings of Germany … since the war.” Next, they shifted gears to replace despair with terror. Hitler and Goebbels indulged in “the most terrific fulminations against Jews and Social-democrats as the sole authors of these sufferings. Self-pity gave place to hate.”

Finally, they offered deliverance, as they “turned from vituperation to self-praise. From small beginnings, the Party had grown invincible. Each listener felt a part of its omnipotence within himself. He was transported into a new psychosis. The induced melancholia passed into paranoia, and the paranoia into megalomania.” Hitler promised paradise on Earth, albeit one that “was only for true Germans and true Nazis. Everyone outside remained a persecutor, and therefore an object of hate.”

This rhetorical pattern is often implemented by authoritarian politicians, including Donald Trump. For example, in 2016 journalist Gwynn Guilford reported that after attending several Trump rallies, “I went through the many reams of observations I scribbled down reflecting on the Trump rallies. Nearly every paragraph fit Money-Kyrle’s sequence.”

The authoritarian leader presents himself as a divine or messianic figure who is uniquely able to vanquish the forces of evil and make the world safe for the faithful. As God incarnate, the leader is by definition omnipotent, omniscient, and omnibenevolent. Because he is all-powerful, he is the only one who is up to the task. Because he is omniscient, everything that he says is true (if the facts do not comport with what the leader says, the facts are wrong). And thanks to his God-like stature, whatever the leader wills is good.

Herein lays a seeming contradiction. In spite of his divinity, the savior must suffer and struggle at the hands of his demonic persecutors—be they the Jews, the communists, or the shadowy forces of the deep state—only to triumph in the end. This is essential not only to the Christian narrative, but is also a common mythological theme that Victorian anthropologist James Frazer christened the story of the dying god.

Hitler crafted an image of himself as a suffering savior early on in his career. In 1923 he approached a German aristocrat named Baron Adolf Victor von Koerber to write a short biography titled Adolf Hitler: His Life and His Speeches. But it turns out that Hitler ghost-wrote his own biography. He wrote the book himself. The book describes itself as "the new bible of today" and used terms such as "holy" and "deliverance" to characterize himself and the National Socialist movement. Hitler also compared himself to Jesus. Consider this passage describing the moment of his political awakening.

This man, destined to eternal night, who during this hour endured crucifixion on pitiless Calvary, who suffered in body and soul; one of the most wretched from among this crowd of broken heroes: this man’s eyes shall be opened! Calm shall be restored to his convulsed features. In the ecstasy that is only granted to the dying seer, his dead eyes shall be filled with new light, new splendor, new life!

Now, back to the present. Given his grandiose self-portrait as the savior of his people, Trump’s loss of the 2020 election, and his current legal tribulations, are fodder for the dying god narrative. His indictment during holy week is perfectly timed for the unfolding of this political passion play (you may recall that Trump is reported to have expressed the desire to be led away in handcuffs, for heightened dramatic effect). And given the vicious Christian doctrine that it was the Jews who murdered Jesus, Trump’s accusation that Alvin Bragg, the prosecutor bringing charges against him, was “hand-picked and funded by George Soros” feeds the religious narrative, as does his statement that Bragg is “doing the work of… the Devil.”

So, what can we expect?

Whatever the outcome of his indictment, the consequences will not be pleasant. If Trump is not convicted, this will be taken by his followers to show that there are sinister powers arrayed against their redeemer—forces over which he has once against triumphed. And if he is convicted, he becomes a crucified God. Just as the success of Christianity required the murder of Christ, it is possible—and I think very likely—that Trump’s conviction will feed the flames of American fascism. Rather than extinguishing the MAGA cult, this will make it stronger, and set the stage for a new, more dangerous messiah to step into Donald Trump’s shoes.

I'm interested to find out more about "our deepest and most insistent hopes and fears." Is there a connection to something that might be called human nature that causes so many people to follow such obviously flawed leaders across time and cultures?

I dunno. Placing Trump and MAGA followers into some sort of religious cult, foretelling doom if he eludes prosecution, and doom if he doesn’t, feeds a self-nourishing narrative. It’s at least as possible that Trump’s narcissism won’t take over our souls and he will fade out of view—much to his and his fanboys’ dismay.

He’s a flawed man and many (most?) on the left are obsessed with, and a portion of the right, the same. For the rest of us, placing him on the same level as Hitler or Jesus simply doesn’t resonate.