The man in the photograph above is Florida congressman Webster Barnaby. The otherwise obscure Barnaby hit the news on Monday because of his remarks about transgender individuals. "It's like we have mutants living among us on planet Earth," he intoned, adding, "We have people that live among us today on planet Earth that are happy to display themselves as if they were mutants from another planet. This is the planet Earth where God created men, male, and women, female. I'm a proud Christian conservative Republican, I'm not on the fence." Adding insult to injury, he went on to proclaim, using ominous, religiously-infused language:

There is so much darkness in our world today, so much evil in our world today and so many people who are afraid to address the evil….The lord rebuke you, Satan, and all of your demons and all of your imps who parade before us. That's right, I call you demons and imps who parade before us and pretend that you are a part of this world. So, I'm saying my righteous indignation is stirred. I am sick and tired of this. I'm not going to put up with it. You can test me and try to take me on, but I promise you I will win every time. Let's all vote up this bill.

The bill in question, the Safety in Private Spaces act, would criminalize trans people who do not use public restrooms corresponding to the gender ascribed to them at birth. After the ensuing uproar, including condemnation by fellow Florida Republicans, presumably worried about voter blowback, Barnaby offered a perfunctory apology: “I would like to apologize to the trans community for referring to you as demons.”

What are we to make of this? The easy, and all-too-common response is to dismiss it as hate-filled speech from a hate-filled man. But I don’t think this is helpful, because effectively combatting transphobia requires us to do more than morally condemn it. We need to dissect its inner workings.

Over the course of nearly two decades, I have been studying the moral psychology of dehumanization and have gradually constructed a theory of how dehumanization works, especially the very dangerous form of it that I call “demonizing dehumanization.” I have mainly researched the racialized form of demonizing dehumanization, but the theoretical apparatus that I have pieced together over the years can be extended (with appropriate modifications) to other dehumanizing or dehumanization-like phenomena, including the demonization of trans people that is exemplified in Barnaby’s derogatory and violent remarks.

The notion of metaphysical threat is at the center of my analysis. To be comprehensible, metaphysical threat must be looked at against the background of a conception of the natural order and relatedly the phenomenon known as psychological essentialism. Psychological essentialism is the very widespread (and possibly universal) disposition among human beings to segment the natural world into discrete kinds of things—for example, biological species. To be a member of a particular kind, one must possess a deep property or essence that only and all members of the kind possess. Essences are deemed to be unmodifiable. An individual is the kind of being that they are forever. And essentialized categories are rigidly bounded. A thing either has a certain essence or not. There’s no grey area in between.

The real world does not conform to the essentialist notion of the natural order. There are always things that transgress the boundaries that we attempt to impose on the world. I argue in my book Making Monsters that this conception of the natural order has a powerful normative component. From this perspective, the order of nature corresponds to how the world should be, not necessarily how the world is. Things can violate the natural order, and thereby become disturbingly unnatural. Such things elicit the feeling of horror, which is the affective component of the experience of metaphysical threat. It then becomes a moral imperative to restore order by aligning the world as it is with the world as it should be.

Consider the following illustrations of metaphysical threat, taken from my article “A theory of creepiness.”

Imagine looking down to see a severed hand scuttling toward you across the floor like a large, fleshy spider. Imagine a dog trotting up to you, amiably wagging its tail – but as it gets near you notice that, instead of a canine head, it has the head of an enormous green lizard. Imagine that you are walking through a garden where the vines all writhe like worms. There’s no denying that each of these scenarios is frightening, but it’s not obvious why. There’s nothing puzzling about why being robbed at knifepoint, pursued by a pack of wolves, or trapped in a burning house are terrifying given the physical threat involved. The writhing vines, on the other hand, can’t hurt you though they make your blood run cold. As with the severed hand or the dog with the lizard head, you have the stuff of nightmares….

As the philosopher Noel Carroll points out, creepiness becomes horror when it is compounded with physical danger or malevolence. In the classic horror film The Beast With Five Fingers the animate severed hand is horrific because it poses both a metaphysical threat and a physical one. The metaphysical threat amplifies the physical threat: a dangerous entity is all the more terrifying if its very being undermines the natural order: if a hand can crawl then, surely, anything might happen. If a hand can crawl, then the comforting, orderly picture of the world threatens to come apart at the seams.

Our culture largely endorses an essentialized gender framework in which there are precisely two genders, corresponding to biological sexes, that are mutually exclusive, immutable, and rigidly bounded. But trans people seem to transgress this boundary. Consequently, and are experienced by some as a disturbing affront to the natural order, a harbinger of metaphysical threat, the human equivalent of a crawling hand.

Now, let’s consider Barnaby’s comments in light of this analysis. First he characterized trans people as resembling mutants from another planet. In ordinary vernacular (for I doubt that Barnaby has even a rudimentary grasp of the science of genetics) a mutant is a “freak”—a repellent departure from the human norm—as the Urban Dictionary puts it, a “hideously ugly, repulsive, decrepid, foul, grotesque, unsightly, horrid, ill-proportioned, mangy, haggard, crude, bloated or generally ghastly person or being” (coincidentally, guru for disaffected young men Jordan Peterson referred to children who have undergone gender-affirming medical treatment as becoming “something like a confused monstrosity” on the same day as Barnaby’s diatribe). Depicting trans people as mutants from another planet expresses the idea that they are repellent, alien beings; certainly not one of “us.”

Barnaby’s next statement is, unsurprisingly, a declaration of essentialism. Here on earth, he says, God created two and only two genders that are coextensive with two sexes, male and female. The creationist story is, of course, an essentialist story, and a normative one at that. The gender binary is part of the natural order ordained by God himself. Barnaby’s next statement—that he, as a conservative Christian—does not “sit on the fence” announces his essentialist bona fides: there are men and there are women, girls and boys, and every human being properly belongs to one or the other of these rigidly demarcated kinds. There’s no middle ground.

If the essentialized gender binary is divinely ordained, it follows that defying that binary is defying God himself—hence Barnaby’s slide from calling trans people alien mutants to calling them demons and imps. This rhetorical transition introduces a new element into the moral psychological mix. As I’ve already said, demonizing dehumanization occurs only when the other is seen as both metaphysically and physically threatening. Recall that Barnaby’s remarks were uttered in support of the Safety in Private Spaces act. The presumption behind the name is that trans people—more specifically, trans women—are sexual predators bent on corrupting, rupturing, and destroying the God-given or nature-given social order. This cocktail of imagined physical and metaphysical threat transmutes the trans community into a community of monsters. In a nutshell, as film scholar Robin Wood famously observed, “Normality is threatened by the monster.”

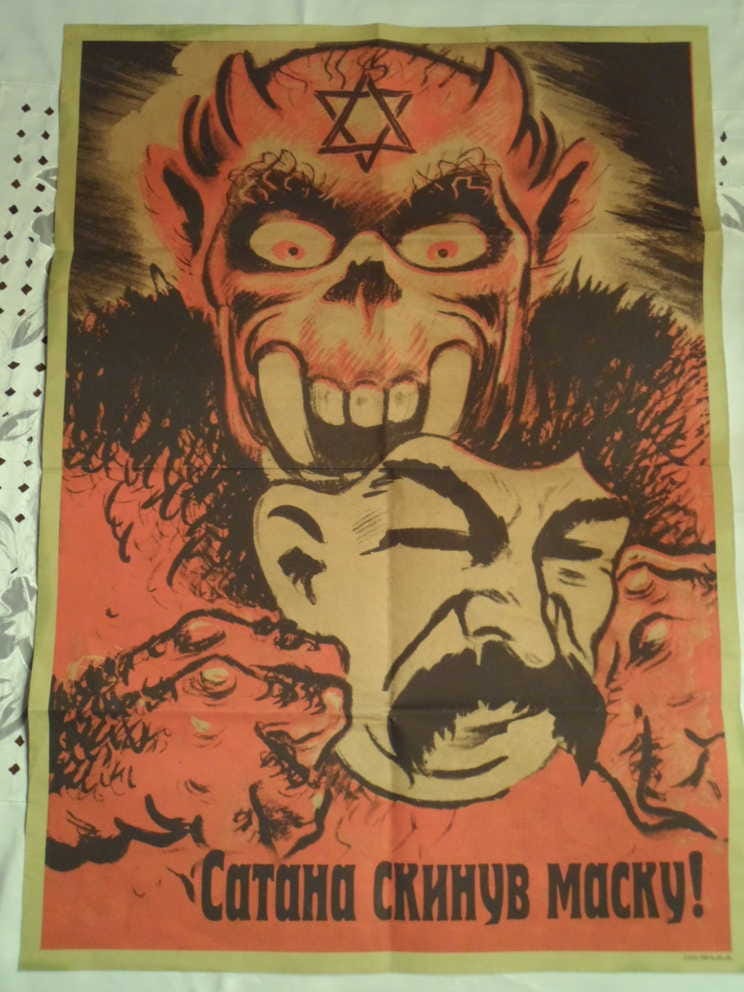

There is a terrible irony at work here. Dehumanized people are usually the most vulnerable members of a society, and yet they are pictured by their persecutors as so powerful and dangerous that they must be brought to heel—segregated, expelled, incarcerated, or even exterminated. This is how White supremacists conceived of African Americans, and how Nazis conceived of Jews, among very many other examples.

This occurs because, as I’ve mentioned, metaphysical threat amplifies physical threat in the minds of dehumanizers. The most threatened members of a population are perceived as the most threatening ones, beings endowed with superhuman powers. Webster Barnaby didn’t just equate trans people as mutants. He actually compared them to Marvel comics’ X-men mutants, who are entities endowed with superpowers.

Soon after Barnaby’s rant, Democratic former state representative Carlos Guillermo Smith tweeted “When Republican Webster Barnaby called trans people ‘demons’, ‘imps’, and ‘mutants’ it wasn’t a mistake or gaffe. It was the hatred and bigotry that’s really motivating Florida’s 20+ anti-LGBTQ proposals finally being spoken into words. Now it’s exposed.” Smith is surely right that Barnaby’s choice of words was not a gaffe or a mistake, and that his words reveal a mindset that is all too common amongst conservative Republicans (and many non-Republicans too). However comments like Smith’s are thin and simplistic. They express moral outrage, but little else. Moral condemnation is often warranted, but to effectively combat dehumanizing trends, we need serious analyses of the ideological and psychological forces that fuel them. This can only be accomplished by teasing out the psychological processes—the aspects of human nature, if you will—that underpin transphobic states of mind.

Thank you for this!!! Yes, we need to understand the thinking behind the fear and hatred, and I really appreciate your explanation of your theory of dehumanization, and the examples you gave. I hadn't made the connection of creating the myth of power around the most marginalized and abused. It's a point that I will continue to think through.