Fascist political movements are manic. There’s nothing subtle about this. Fascism wears its mania on its sleeve like a swastika armband.

We’ve all seen this during the Trump regime. Trump describes whatever he does as huge, epoch-making, biggest, and best. Not content with being good enough, he proclaims—often in all capital letters punctuated with an abundance of exclamation points—that he is ushering in a Golden Age for the United States, an era of unprecedented peace and prosperity, a miraculous rebirth.

Manic frenzy isn’t just incidental to fascism. It’s the core of the fascist mentality. The Nazis were intoxicated with it, as are members of the MAGA movement today. Hitler was no mere leader. He was the inspired prophet and architect of a thousand-year Reich (which turned out to last only twelve years). As Johann Chapoutot describes in Free to Obey: How the Nazis Invented Modern Management

The time was “historic.” Nazi discourse was fond of hyperbole and bragging. Judging by the texts, speeches, pictures, and films, everything was “historic,” “unique” (einmalig), “gigantic,” “decisive” (entscheidend), and so on, ad nauseam.

Hitler used a rhetorical strategy that was geared towards inducing a manic state of mind in his audience. This has been described by quite a few historians and journalists. Here’s an account by the British writer Amy Buller. from her book Darkness over Germany: A Warning from History, first published in 1943.

With consummate skill he [Hitler] got his audience to feel the despair and desolation of Germany, and then, working himself up into a frenzy; he thundered at this youthful crowd. I do not remember all his words, but the main points remain vivid in my mind….”For years this country has been ruled by men who were defeated in spirit. Their favorite theme was that there was ‘no way out’ and that the fault was everyone else’s but their own. You have heard them say again and again that all the desolation and distress in Germany was due, first to defeat [in World War One] and secondly to forces outside this country. I deny all that….No power, no country in the world can stop Germany from rising again.

Having first painted a sombre picture of the sufferings of Germany since the Great War, and then blamed this on the enemy within, Hitler continued in a more uplifting vein.

He had worked up his audience into a frenzy of excitement now, but he went on with unabated fury. “Politicians all the world over talk of difficulties. We are not interested in difficulties, we are only interested in success…. Germany has been kicked, scorned, and driven to despair and none within her have had the courage to revolt and defend her right to live. If you are passionately, blindly loyal and obedient, then I will tell you that… things will happen that will startle the world. I bring you a faith that cannot be defeated.”

Notice the sequence. First, Hitler paints a heart-rending portrait of the sufferings of Germany. Next, he blames this suffering on internal enemies. And finally, he makes an inspirational appeal to his audience to unite behind him to make Germany great again.

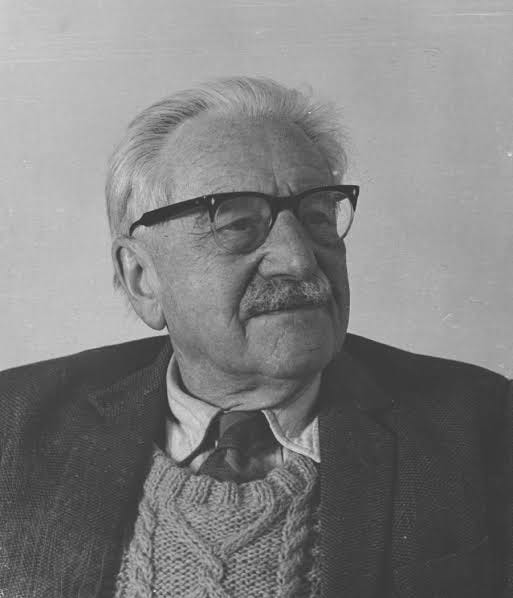

I’ve written quite a bit about Roger Money-Kyrle’s insights into the psychology of fascist rhetoric, both on this platform and elsewhere. For those new to my work, Roger Money-Kyrle was an English psychoanalyst and philosopher who visited Germany in 1932, where he heard Hitler and Goebbels give speeches encouraging Germans to vote Nazi in the impending German national elections.

Money-Kyrle was fascinated by what he heard and saw, and described his experience, and his analysis of it, in an article titled “On the psychology of propaganda,” which was published in the British Journal of Medical Psychology in 1941. He explained that Hitler’s first got his audience to feel depressed, then he got them to feel paranoid. Finally, he offered them the promise of deliverance, at which point the audience “became self-conscious of its size, and intoxicated by the belief in its own omnipotence.” “Each listener…was transported into a new psychosis. The induced melancholia passed into paranoia, and the paranoia into megalomania,” a state of “manic bliss.”

The terms “omnipotence,” “megalomania,” and “manic bliss” have a technical psychoanalytic meaning. All three terms are more or less coextensive, but here I want to concentrate on unpacking just one of them— the psychoanalytic take on the dynamics of “manic bliss.”

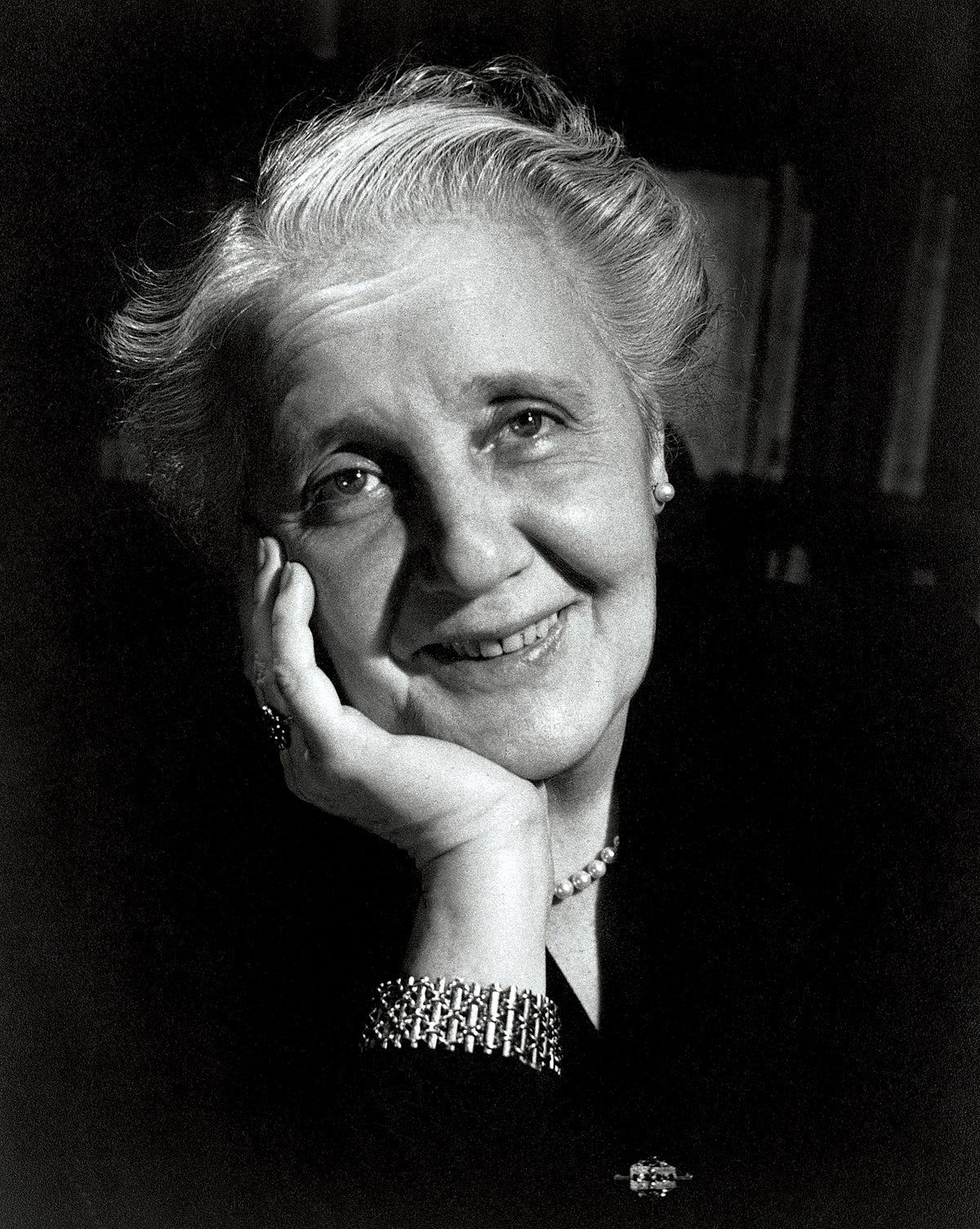

To understand what Money-Kyrle meant by this phrase, we must delve into the work of the person who influenced him more than anyone else: the Polish-born psychoanalyst Melanie Klein. The framework that Money-Kyrle used to make sense of Nazi propaganda, and by extension, propaganda generally, came from Klein’s work.

Before I switched to philosophy I was a psychoanalytic psychotherapist, taught psychoanalytic theory and practice, and clinically supervised trainees. Even in those days, when I was immersed in the psychoanalytic scene, I had problems Kleinian theory and practice. Klein was an undisciplined thinker, and her views on the psychological development of infants were, to be excessively generous, very speculative. However, she also had a remarkably sensitive grasp of the phenomenology of disturbed and disturbing mental states. Shorn of its theoretical superstructure, this framework has considerable descriptive value.

The most straightforward way to make sense of Klein’s notions of paranoid and depressive anxieties has to do with the subjective sense of the location of danger. When we experience paranoid anxiety, we feel that some dire threat exists outside of us—the badness is out there in the world. In states of depressive anxiety, we feel that we are the destructive ones, rather than some external enemy.

Let’s return for a moment to Buller’s description of Hitler’s rhetoric, and look at it through Kleinian spectacles. First, Hitler evoked feelings of despair and desolation in his audience. That’s depressive anxiety. Given that Germany was on its knees in the aftermath of its defeat World War I, the hardships imposed by the Treaty of Versailles, and then the Great Depression, Hitler didn’t have to work very hard to tap this reservoir of wretchedness.

Next, he blamed Germany’s situation on his political enemies. That’s paranoid anxiety. This was no doubt attractive to his audience. It is comforting to blame others for one’s misfortunes.

What about mania? In Buller’s account, mania comes in at the end, when Hitler talks about success and how under his leadership things will happen that will “startle the world” because the Nazi faith “cannot be defeated.”

Money-Kyrle referred to this rhetorical moment as “manic” because he had in mind what Klein called the manic defense. In psychoanalytic lingo, defenses are mental processes with the function of pre-empting distress. The manic defense consists of a triad of attitudes—triumph, control, and contempt—all of which have the function of denying depressive helplessness, vulnerability, and defeat. Manic defenses replace the “low” of depression with the “high” of megalomania—the feeling that one is all-powerful and thus invulnerable.

Fascist leaders induce the manic mood by what I call trickle-down omnipotence. Recall Buller’s remark that Hitler concluded his speech with a passionate appeal to Germans to unite behind him. Money-Kyrle also observed that after playing on his audience’s feelings of vulnerability, and claiming that he could rescue Germany, this putative giant among men did something else.

Hitler made his great appeal for unity. This seemed to me to be the secret of his success. If, like some of his disciples, he had nothing but thunderbolts to offer, he could hardly have remained the god he is. But he also stirred the unconscious longing for the ideal family, in which no one should be injured and everyone should be at peace. This Paradise, however, was only for true Germans and true Nazis.Everyone outside remained a persecutor, and therefore an object of hate.

By appealing to the Volksgemeinschaft—the racial community—Hitler invited Germans to transcend their individual identities and identify with him: Ein Volk, ein Reich, ein Führer! Followers who are “passionately, blindly loyal and obedient” to the movement—something much greater than themselves—can participate in the leader’s megalomania, emancipated from their hopelessness, their fear, and and their insignificance.