Several years ago I was invited to take part in an event called the Ubuntu United Nations, sponsored by an organization called Ubuntu Leaders Academy which brings together young people from all over the world. It “is dialogue platform that seeks to bring change makers across the world to speak on issues affecting them, to learn and share ideas with leaders such as Nobel Peace Prize laureates, former heads of state and other global leaders through intergenerational dialogue.” The Ubuntu Network reaches more than one hundred thousand young people world-wide.

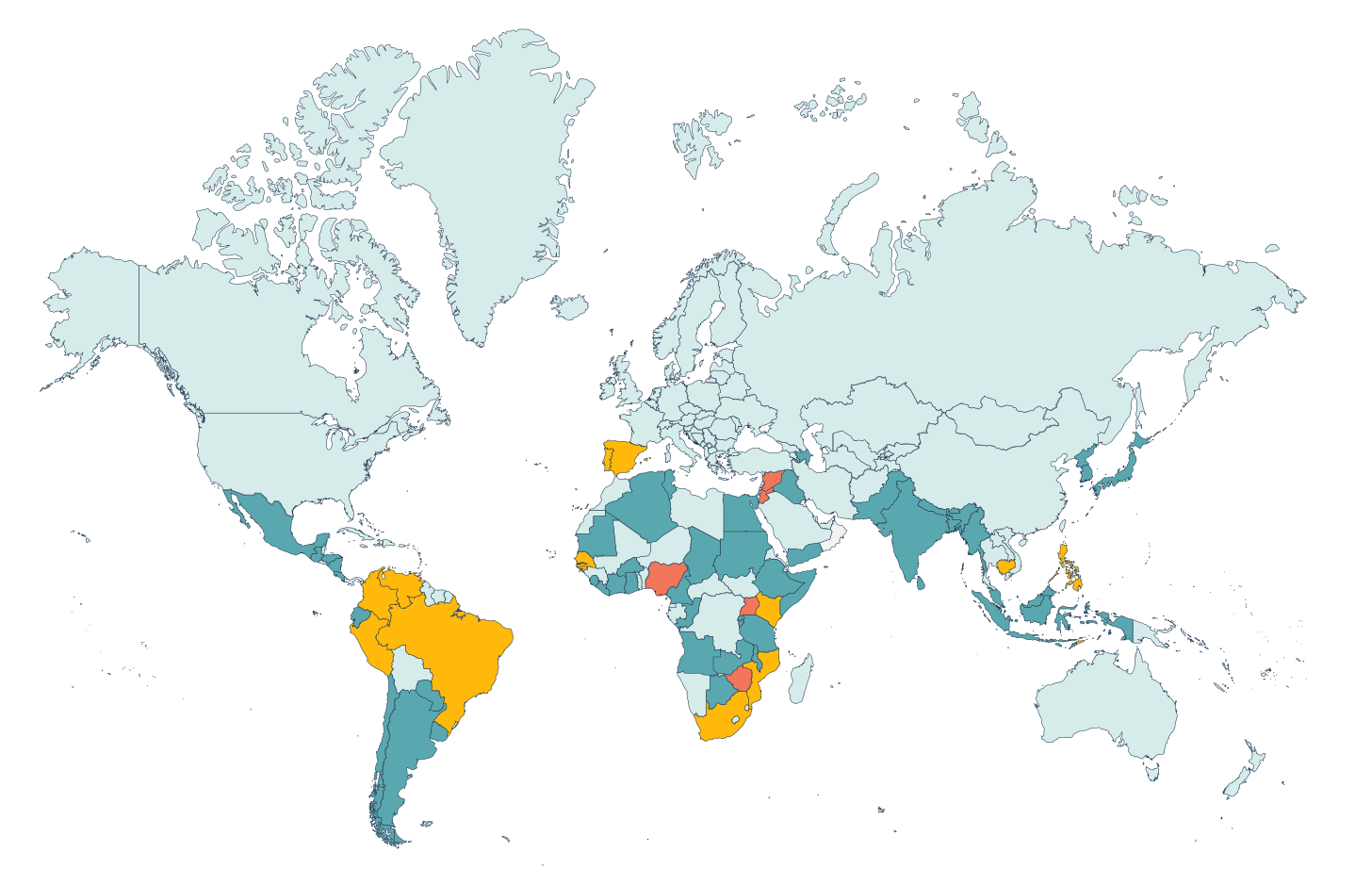

I was deeply honored to be invited to speak at this event, and to join a very impressive group addressing six hundred young people, from 190 countries. This is what I said to them.

Today, I want to address a matter of extreme urgency that is too often ignored. I want to share my life’s work: the study of dehumanization.

Dehumanization is a way of thinking about other people. When people dehumanize others, they think of them as less than human, typically they think of a whole group of people as less than human, as dangerous animals, as unclean beasts, as vermin, as monsters, as demons. This is very important because dehumanization has been linked with the very worst things that human beings have done to one another: genocide, war, oppression, slavery and other atrocities.

Past generations have not addressed the phenomenon of dehumanization properly. People may talk about it but pivotal tasks remain in terms of understanding it, getting inside it, figuring out how it works, why it happens and how to stop it. After all, if we do not understand how something works and how it is put together, we do not stand much of a chance of dismantling it and putting an end to it. In the case of dehumanization, this is an urgent task, particularly in light of the challenges that humanity will face in the century to come.

My research has taught me a lot about dehumanization. This phenomenon does not come naturally to the human mind; it does not simply occur to people to think of other people as less than human. Dehumanization happens under the influence of propaganda and ideology when people in positions of power - be they politicians, religious leaders, celebrities or anyone with an influence on the views of the general population - convince us that there are whole groups of people who might look human, who might seem human, who might act like human beings, but who are not on the inside truly human beings: they are beasts, blood thirsty predators, vermin, unclean animals, demons, monsters, and this sort of rhetoric.

When people in positions of power frighten us into thinking of others that way it leads to terrible acts. So, dehumanization does not come from within, it comes from outside; it comes from people convincing us to override our perceptions of others as human beings.

When we look at another human face and look into another pair of human eyes, we simply cannot help but see that other person as a human being as well. Nevertheless, people in positions of power are skilled in propaganda; they are able to convince us, and lead us, to do terrible things to one another. And they convince us that in doing so, we are doing the right thing and, in some way, saving the world from evil.

In every genocide that I have studied, the perpetrators of atrocity think that they are morally in the right; they are convinced that they are ridding the world of evil by exterminating whole populations of human beings.

Another thing that I have learned during my years of research is that all of us are potential dehumanizers.

It is quite tempting to think that people who are capable of considering human beings as less than human are monsters. They are not. They are ordinary people like each one of us. To realize this is key. We have to hold a mirror up to ourselves and see the kind of things we are capable of doing under the right circumstances. There is no such thing as monsters. Monsters are imaginary. All of the most brutal acts that human beings have perpetrated on one another, are perpetrated not by monsters, but by other human beings.

These considerations show how vital it is for young people to find ways to resist the forces of inhumanity, to find ways of not becoming part of the atrocities that have scarred humanity for thousands of years, to resist and to help others to resist. But we can only do this if we understand the phenomenon we are dealing with. If we understand dehumanization, rather than becoming victims of it and perpetrators of it, we can work together to combat it, to eliminate it, to dismantle it, and to find better ways of carrying out the human project.

Earlier generations failed to make sure the world would become a better place. Young people are the future. This generation, and the next, have the opportunity to do better than past generations did.

This May, I will speak to youth leaders from 193 countries at the 2024 Ubuntu United Nations. I will speak against the background of a looming climate crisis, and a planet ravaged by wars, oppression, and multiple genocides. I hope that I will be equal to the task of conveying to them the urgency of our situation and the enormity of the challenge of repairing our world that will soon fall upon their young shoulders. I hope.