The photograph above is of Joan Salter. Born Fanny Zimetbaum, eighty-four-year-old Salter is a Holocaust survivor. She was only a baby when the Germans invaded Belgium, and her family was forced to flee to save their lives. Salter has been in the news in the UK because of her challenge to Suella Braverman, the British Home Secretary, who once described her job as being “about stopping the invasion on our southern coast.” Salter recently confronted Braverman at a public event, and said to her:

In 1943, I was forced to flee my birthplace in Belgium and went across war-torn Europe and dangerous seas until I finally was able to come to the UK in 1947. When I hear you using words against refugees like ‘swarms’ and an ‘invasion,’ I am reminded of the language used to dehumanize and justify the murder of my family and millions of others.

And then she asked the Home Secretary, “Why do you find the need to use that kind of language?” Here is a video of their exchange.

As you can hear, Braverman’s evasive response elicited applause from her audience.

Salter, who is an indefatigable advocate for Holocaust education, followed up in an op-ed published in The Guardian newspaper:

The language of hate and division….was the method used by the Nazis to turn ordinary people, who went home each night to their wives and children, into the monsters capable of marching millions of Jews and other minorities – people just like them – into the gas chambers. It is what enabled ordinary soldiers to return to their wives and children, satisfied that they were protecting their country from social problems caused by people whom their government had convinced them were less than human.

To be fair, Braverman has never publicly described refugees and asylum seekers as a “swarm.” But her conservative fellow travelers certainly have. For example, prime minister David Cameron told journalists in 2015 that “a swarm of people” were “coming across the Mediterranean seeking a better life,” and Nigel Farage, who was at the time leader of the far-right UK Independence Party, said during a television interview that he had been “stuck on the motorway and surrounded by swarms of potential migrants.” The Home Secretary’s language needs to be heard in the context of a conservative ideological ecosystem—one in which remarks characterizing desperate people caught up in a human rights crisis as “invaders” (and therefore as having malevolent intent) triggers a cascade of dehumanizing tropes in the minds of her listeners.

You might find this puzzling, and wonder what all the fuss is about. After all, to say that migrants are invaders is a far cry from referring to them as “monsters” or “subhumans.” But that response would be far too hasty. The fact is that in many societies, including Great Britain and the United States, overtly dehumanizing rhetoric has become socially unacceptable outside of extreme right-wing circles. But this does not mean that dehumanizing attitudes have somehow evaporated. It only indicates that, bowing to current social norms, dehumanizing attitudes must be expressed indirectly in a manner that is hospitable to plausible deniability. They’ve not gone away. They’ve just gone under cover.

I wrote about covert dehumanization in my 2020 book On Inhumanity: Dehumanization and How to Resist It as follows:

There are certain themes that reappear again and again in this kind of indirectly dehumanizing discourse. A common one is criminality. The dehumanized group is made to appear inherently threatening and their criminality is represented as crudely animalistic—typically involving rape and murder. Another common theme is parasitism. The dehumanized group conspires to exploit the majority, sucking the blood out of decent, honest, working people, and claiming privileges that they haven’t earned. Images of filth and disease are also very frequent. Dehumanized groups are vectors of infection. They are dirty and contaminating. They are often thought of as invaders, outsiders who are taking us over. They’re reproducing at an alarming rate, and they will soon outnumber us unless we can do something about it. These descriptions are usually laced with dehumanizing metaphors that nudge the audience into thinking of the group as a lower order of beings. They “swarm” and “scurry” across borders to “infest” the nation. And the places where they gather are “breeding grounds” for violence and terrorism.

When a person uses language like this, they don’t have to use words like “vermin” to dehumanize a group. Nudge listeners in that direction by using the right sort of evocative language and they’ll connect the dots all by themselves. They’ll form an image of the targets of this rhetoric as subhuman creatures, sometimes without even realizing that they are doing so, without the speaker ever having uttered an animalistic slur. And the purveyor of dehumanizing speech has plausible deniability on his side. He can say that he had no such thing in mind

Competent propagandists are aware that the majority of those whom they are trying to influence might find explicit references to a targeted group as literally less than human difficult to swallow, and bank on them being hospitable to a more oblique approach.

One way that this is accomplished is visually, through cartoons and posters, because dehumanizing representations of racialized groups can easily be dismissed as “just a mataphor” even though they are aimed at eliciting dehumanizing attitudes in the minds of consumers.

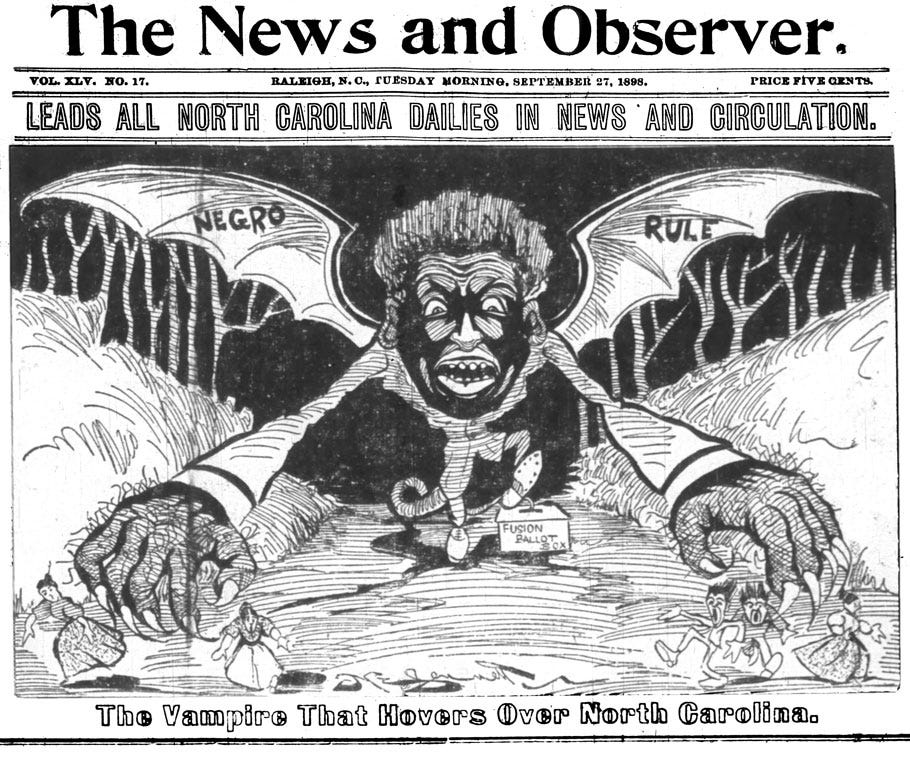

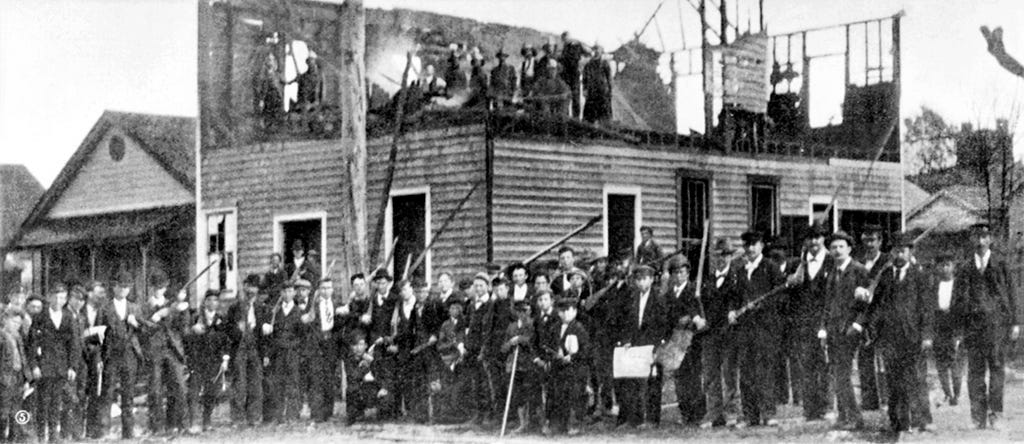

The illustration above depicts a monstrous Black man preying on tiny White people that he is poised to devour. It was published in November, 1898 to incite violence against African Americans in Wilmington, North Carolina. That same month, a mob of around 2000 White people trawled through the city, hunting down and killing at least twenty-five and perhaps hundreds of its Black residents. According to one contemporary account:

It was a great sight to see them marching from death, and the colored women, colored men, colored children, colored enterprises and colored people all exposed to death. Firing began, and it seemed like a mighty battle in war time. The shrieks and screams of children, of mothers, of wives were heard, such as caused the blood of the most inhuman person to creep. Thousands of women, children and men rushed to the swamps and there lay upon the earth in the cold to freeze and starve. The woods were filled with colored people. The streets were dotted with their dead bodies. A white gentleman said that he saw ten bodies lying in the undertaker’s office at one time. Some of their bodies were left lying in the streets until up in the next day following the riot. Some were found by the stench and miasma that came forth from their decaying bodies under their houses.

This cartoon is explicit without being literal. It was not to convey the idea that Black men are gigantic entities with wings and claws; it was to reminded White supremacists that Black men are dangerous, rampaging monsters that need to be destroyed.

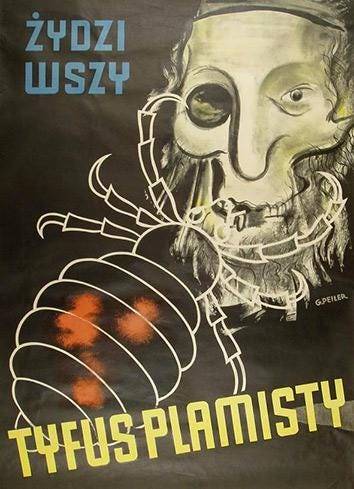

The theme of infectious disease, and dehumanized groups as harbingers of disease is a common theme in dehumanizing propaganda. The representation of Jewish people collectively as a plague poisoning the blood of the German racial community, or as bringers of disease such as rats and lice, was a mainstay of Nazi propaganda. Like the White supremacists of Wilmington, the Nazis were up-front about depicting their supposed racial inferiors as subhuman, as is exemplified by the 1941 propaganda poster reproduced below, which states, in Polish, “Jews are lice. They bring typhus.” The point was not to say that Jews are literally lice (even on the poster, the death’s head Jewish face is distinct from the image of the louse). Rather, it was to make salient the idea that Jewish people are infectious, dangerous subhumans.

Now, compare the Nazi poster with a cartoon published in the Spanish newspaper La Tribuna de Albacete, on November 28, 2021.

The cartoon depicts the omicron variant of covid 19 as a crowded boat-full of dark-skinned, full-lipped people sailing to the European Union (indicated by the flag in the distance). Here, African asylum-seekers (the boat bears the image of the South African flag) are represented as a dangerous pathogen threatening Europe. In this case, there is no bald statement that Africans are a deadly disease, and African migrants are a menacing infestation, but the cartoon urges readers to draw that conclusion themselves, while leaving open the option of saying “No, it’s just a metaphor!”