Weeding Out Race

How Plants Can Help Us Think About Race

In the spring, I have a lot of dandelions growing in my yard. They seem to pop up everywhere. Similarly, a mass of poison ivy runs wild around the edges, where the lawn meets the woods. And crabgrass, ragweed, and other botanical invaders all announce their presence.

To my chagrin, there’s no shortage of weeds around my house. But what exactly is a weed?

Let’s start with the common dandelion as Exhibit A. Biologists tell us that the common dandelion belongs to the species Taraxacum officinale, and therefore the genus Taraxacum. Further, it’s a member of the family Asteraceae, the order Asterales, the class Magnoliopsida, the phylum Magnoliophyta, and the kingdom Plantae.

Notice that the word “weed” doesn’t appear anywhere on this taxonomic list. And none of the Latin terms are its equivalent. That’s because “weed” is not a scientific term. Weeds do not fall within a single biological category. Biological taxonomies are aimed at setting out the objective structure of the relations between kinds of living things. They describe what philosophers call natural kinds—objective divisions of the natural world. All of the members of each natural kind category have shared features that make them members of that category, and which distinguish them from other categories. Although biological taxonomy is not as clear-cut as its chemical counterpart (think of the little boxes arrayed on the periodic table of the elements), members of the genus Taraxum, such as the dandelion, have features in common that distinguish them from members of the genus Toxicodendron, such as poison ivy.

In contrast to the genus Taraxum, the category “weed” isn’t biologically unified. There aren’t any biological properties that are unique to weeds, setting them apart from other kinds of plants. Imagine an alien super-biologist who knows all there is to know, biologically speaking, about plants on Earth. Even though the alien scientist knows literally every biological fact about all plants inhabiting our planet, he wouldn’t be able to tell weeds apart from other kinds of plants.

The category “weed” is “socially constructed.” What makes a plant a weed is the role that it plays in human social life. As Richard Mabey writes in his book Weeds: In Defense of Nature’s Most Unloved Plants, “The best-known and simplest definition is that a weed is ‘a plant in the wrong place,’ that is, a plant growing where you would prefer other plants to grow, or sometimes no plants at all.”

Membership in the category “weed” is unstable and context-dependent. A dandelion growing on a lawn is a weed, but the same plant growing in a meadow is a wildflower. A plant that’s a weed in one culture might be a medicinal herb in another. Plants can move in and out of the weed category as cultural practices change. Weeds didn’t exist before humans began practicing horticulture, even though the very same plants that we call weeds today existed before there were any weeds.

Now it’s clear why our alien biologist, working on his own, would draw a blank when asked which earthly plants are weeds. To answer that question, he would need to collaborate with an alien cultural anthropologist who possessed a detailed knowledge of the historical and geographical distribution of human social practices.

Races are like weeds. They’re not like natural kinds such as Taraxacum officinale.

Most people regard human races as natural, biological kinds. Until quite recently, this was the unexamined consensus among scientists, too. However, the last half century of biological research into race has demonstrated that races are not natural kinds. Like weeds, races are not biologically unified, and also like weeds, races are hostage to changing historical contingencies and cultural practices. The Irish are a standard example. As Kenan Malik notes in Not So Black and White: A History of Race from White Supremacy to Identity Politics:

The first group that posed the question for the American elite of “Who is white, and to what degree?” were the Irish….The Irish were seen not just as socially and culturally but also as physically distinct, “low browed,” “brutish,” even “simian.” “To see white chimpanzees is dreadful,” the English historian and clergyman Charles Kingsley observed of Ireland.

Irish people are no longer considered as belonging to a separate, non-White race. The same can be said of most of the forty-five races listed in the 1911 congressional Dillingham Commission report, thirty-six of which consisted of indigenous Europeans. It is unlikely that the conception of the Black race existed prior to incursions of European and Arab slavers into sub-Saharan Africa.

In previous essays, as well as my most recent book, I’ve made it clear that I am what philosophers call an anti-realist rather than a social constructivist about race. Social constructivists hold that social practices and beliefs bring races into existence—that races are both socially constructed and real. Anti-realists (sometimes called “eliminativists”) differ from them in denying that such practices and beliefs bring races into existence.

The view that races are fictional seems to be at odds with my comparison of races with weeds. I wrote in the very first paragraph of this essay, “There is an abundance of weeds around my house.” This shows that I think that weeds exist. After all, there can’t be an abundance of weeds unless there really are weeds! So how come I accept the existence of weeds but not the existence of races?

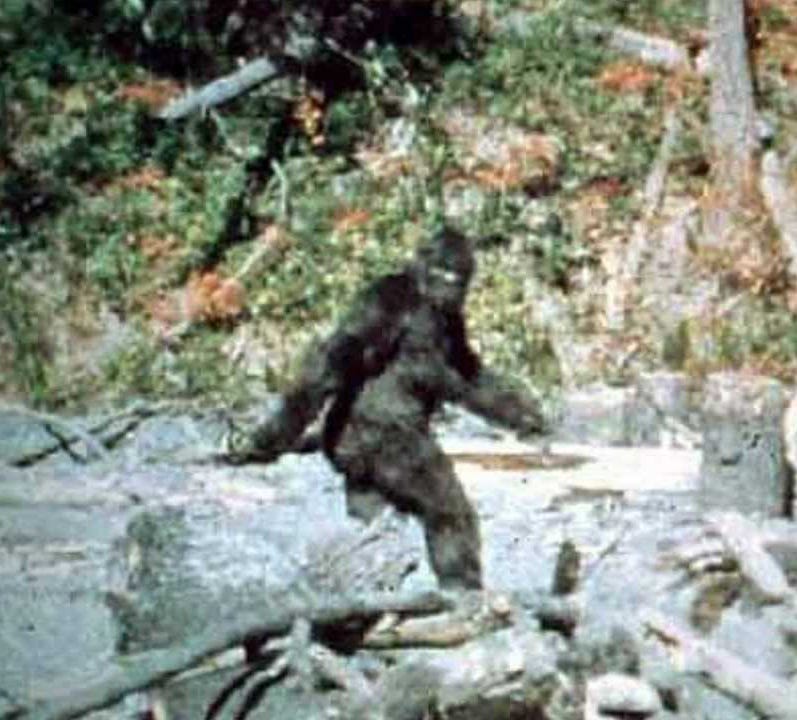

To make a call about whether something exists, we’ve first got to ask what that thing is supposed to be. Does Bigfoot exist? Well, what do you mean by “Bigfoot”? Bigfoot is supposed to be a large, hairy, humanoid creature living in remote areas of the Northwestern United States. Once we’ve decided what Bigfoot is supposed to be, we can ask whether there is anything in the world that actually fits this description. If there is, then Bigfoot exists, but if not, then Bigfoot doesn’t.

The same procedure applies to plants. Weeds are supposed to be plants in the wrong place, and there really are plants in the wrong place, so weeds really do exist. But this can’t be said for races, at least as the concept of race is commonly understood. As I’ve mentioned, the default assumption about race—one that is cemented into the foundation of American and European culture—is that race is a biological property. The view that there are races is the view that there are a small number of biologically distinct kinds of human beings, that everyone is either a pure specimen of one of these kinds or a mixture of two or more of them, that one’s race is inherited biologically from one’s ancestors (most proximately, from one’s parents), and therefore that classifying people by race tells us a great deal about them.

This notion of race is inconsistent with the verdict delivered by our best science. There’s nothing in the world corresponding to it. So, races do not exist.

A common rejoinder from self-proclaimed race realists is that genetics tells a different story than what I am claiming here. They tell us, for example, that genetic analysis can assign people to their self-ascribed race close to 100% of the time, and that this demonstrates that race is underwritten by biology. But it actually demonstrates no such thing.

Genetic analysis can determine that (for example) an individual very likely has substantial European ancestry, but it cannot tell us that that individual, or any other individual, is White. If this sounds odd, consider once again the humble dandelion. A genetic analysis of a dandelion leaf can establish that that leaf came from Taraxacum officinale, but it cannot establish that the leaf came from a weed without a prior commitment to the idea that dandelions are weeds. And that prior commitment can’t come from biology. It can only come from an understanding of human social practices.

A similar point can be made about claims about the genetics of race. Neither social constructivists nor antirealists about race deny that phenotypic patterns associated with racial categorization are largely under genetic control. What we do deny is that this fact has much of anything to do with the supposed biological vindication of race.