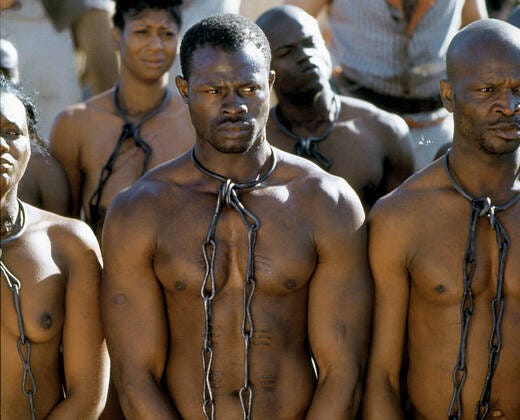

The picture above is a still from Steven Spielberg’s blockbuster movie Amistad. The man in the middle is the model and actor Djimon Hounsou, who plays Joseph Cinqué, the leader of a shipboard slave revolt. In the movie, Hounsou has just survived the ordeal of the Middle Passage, the two-to-three-month journey from the west coast of Africa to the plantations of the Americas. Describing the passage as gruesome would be too mild. Prisoners were shackled together and densely packed below deck, in dark, filthy, cramped conditions. They were beaten and deprived of oxygen, food, and water. Disease, including smallpox and dysentery, was rampant, and many of them perished before reaching their intended destination. Some took their own lives by jumping overboard. Others, deemed too sick to sell, were fed to the sharks.

Here is how former slave and abolitionist Olaudah Equiano described it in his memoir:

The closeness of the place, and the heat of the climate, added to the number in the ship, which was so crowded that each had scarcely room to turn himself, almost suffocating us. This produced copious perspirations, so that the air soon became unfit for respiration, from a variety of loathsome smells, and brought on a sickness among the slaves, of which many died, thus falling victims to the improvident avarice, as I may call it, of their purchasers. This wretched situation was again aggravated by the galling of the chains, now become insupportable; and the filth of the necessary tubs [large buckets for human waste], into which the children often fell, and were almost suffocated. The shrieks of the women, and the groans of the dying, rendered the whole a scene of horror almost inconceivable.

Here is an image published in Harper’s Weekly in 1860 depicting the deck of a slave ship that was intercepted near Key West, Florida (although slavery was still practiced in the United States, the transatlantic trade had been abolished since 1808, and American ships patrolled coastal waters). The accompanying text explains that this ship, which was intercepted by an American steamer, was found with more than five hundred enslaved Africans on board.

About fifty of them were full-grown young men, and about four hundred were boys aged from ten to sixteen years. It is said by persons acquainted with the slave-trade and who saw them, that they were generally in a very good condition of health and flesh, as compared with other similar cargoes, owing to the fact that they had not been so much crowded together on board as is common in slave voyages, and had been better fed than usual. It is said that the bark is capable of carrying, and was prepared to carry, one thousand, but not being able without inconvenient delay to procure so many, she sailed with six hundred. Ninety and upward had died on the voyage. But this is considered as comparatively a small loss, showing that they had been better cared for than usual. Ten more have died since their arrival, and there are about forty more sick in the hospital. We saw on board about six or seven boys and men greatly emaciated, and diseased past recovery, and about a hundred that showed decided evidences of suffering from inanition[1], exhaustion, and disease. Dysentery was the principal disease.

Look hard at this picture. These men and boys are emaciated. Many are ill and many have died. It’s not a photograph, but given our knowledge of the Middle Passage it is far more realistic than the images in Amistad. And note that these people are described as “in a very good condition…as compared with other similar cargoes.”

The conditions on slave ships were similar to those in Nazi concentration camps. The illustration from Harper’s Weekly is more like this photograph of survivors of Dachau than anything offered by Hollywood, however well intended.

Djimon Hounsou is nothing like these desperate, broken men. Hounsou has carefully cultivated his impressive physique. He works out six days a week and “makes sure to prioritize healthy food that’s rich in protein…and he protects his immune system with nutritious fruits and veggies…. He doesn’t believe that nutritious food has to be bland, so Djimon eats everything from egg whites to crispy wraps, fruity oatmeal to juicy meat sandwiches, and more.”

The contrast between cinematic image and historical reality could not be starker or more grating, and it goes beyond representations of the Middle Passage in the entertainment industry. It’s common for actors with vigorous, muscular bodies to be cast in the role of enslaved men. But this is a gross distortion of the terrible reality. As Thomas A. Foster points out in his book Rethinking Rufus: Sexual Violations of Enslaved Men

The….diet of enslaved men was such that many men’s musculature would have been retarded or disproportionate from repetitive work. Bones would have been weakened from calcium deficiencies. One man who had been enslaved in South Carolina explained how little they received to eat: “The time of killing hogs is the negroes’ feast, as it is the only time that the negroes can get meat, for then they are allowed the chitterlings and feet; then they do not see any more till next hog-killing time. Their food is a dry peck of corn that they have to grind at the hand-mill after a hard day’s work, and a pint of salt, which they receive every week. Similarly, another man discussed his experiences in Georgia and how much work was required on very little food: “[The owner] would make his slaves work on one meal a day, until quite night, and after supper, set them to burn brush or to spin cotton.” He continued: “Our allowance of food was one peck of corn a week to each full-grown slave. We never had meat of any kind and our usual drink was water.”

Children were also malnourished. Frederick Douglass recalled:

Our food was coarse corn meal boiled. This was called mush. It was put into a large wooden tray or trough, and set down upon the ground. The children were then called, like so many pigs, and like so many pigs they would come and devour the mush; some with oyster-shells, others with pieces of shingle, some with naked hands, and none with spoons. He that ate fastest got most; he that was strongest secured the best place; and few left the trough satisfied.

Malnutrition resulted in developmental deficits and left these people open to disease. Foster goes on to inform readers that:

One man, for example, a field hand named Frederick, was “covered with ulcers” and “rotten.” He died before he was fifty. Runaway notices include descriptors such as “bowlegged” and “bandy-legged,” a condition that was probably caused by poor diet. Those enslaved by John Henry Hammond were “extraordinarily unhealthy” because of the diet and treatment that were part of life on his plantation. Masters… “provided only what was minimally necessary for [slaves’] maintenance as effective laborers.” The standard diet supplied “inadequate amounts of calcium, magnesium, protein, iron, and vitamins.”

What’s going on? Why are we not outraged at the misrepresentations of enslaved Africans? Why do so many people tolerate or even celebrate these images, and do not even notice their flagrant departure from reality? Answers to these questions aren’t difficult to come by. They are part of the dishonest ideological legacy of slavery itself. These idealized images of the so-called Black male body—which, ironically enough, were commonly purveyed in nineteenth century abolitionist literature—amount to a callous denial of these men’s suffering and vulnerability, and a corresponding affirmation of the big Black buck of the racist imagination, shamefully disguised as a celebration of Black masculinity.

To be clear, I am not asserting that Steven Spielberg, Djimon Hounsou, or anyone who enjoys watching Amistad is a racist. Amistad is a good movie, but to grapple with the truth we must look deeper, at a reality that is more disturbing and morally repellent. We Americans produce and consume such cinematic fare because our minds have been so thoroughly colonized by the ideological legacy of White supremacy that we are blind to facts that stare us in the face. Think about it. It would have been grotesque to cast the young Arnold Schwarzenegger as a prisoner in Auschwitz. It would be a betrayal of the memory of the millions who suffered and died there. Truly honoring the memory of those who suffered and died on the slave ships and plantations requires us to confront the truth about the past, and its legacy in the present, rather than indulging in historical fictions, no matter how uplifting they may seem to be.

.

[1] “Inanition” is the state of physical and mental collapse due to lack of food and water.

I'm embarrassed that this had not occurred to me before, and I thank you for this piece. I think the film industry assumes that physical attractiveness is necessary for audiences to identify, care about, or empathize with characters. Audiences need to see themselves in a character, and also want to see themselves as more attractive than they are in reality. The impact of cinema to thus distort and rewrite history is doubly disturbing, because so many "learn" their history from movies today, versus books or scholars, like yourself. That is why I hope this newsletter gains the following it deserves.

Thank you for this essay -- I had never realized, though after reading this it seems obvious.