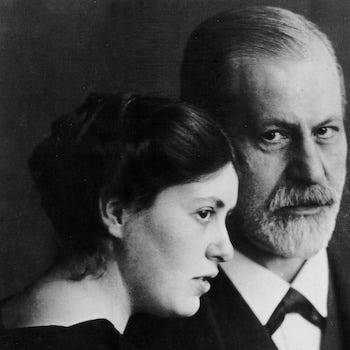

I came to philosophy via psychoanalysis. Previous to transitioning to philosophy, I practiced psychoanalytic psychotherapy, taught psychoanalysis to MA students, and clinically supervised interns providing therapy to children. My PhD dissertation was a study of Freud’s philosophy of psychology (published under the title Freud’s Philosophy of the Unconscious), and all of my early philosophical work was on philosophy of psychoanalysis.

Lately, I’ve had the urge to return to my intellectual roots and write a new book about Freud. Many of my friends—especially my psychologist friends—regard my fondness for Freud as a grave intellectual shortcoming. They regard Freudian thought as, at best, a pre-scientific fossil and at worst the ravings of a cocaine-addled mind. But I think that there is a great deal of value to be mined from Freud’s writings. That’s why I’ve decided to post occasional essays about Freud on this Substack, starting with this one.

Sigmund Freud began his professional career as a neuroscientist, not as a psychologist or a psychiatrist. He wrote approximately 200 neuroscientific publications and was a world expert on aphasia and what’s nowadays called cerebral palsy. Even at this early stage of his work, Freud had radical ideas. One such was his take on the mind-body problem.

The mind-body problem is one of the traditional topics in philosophy that goes back hundreds or even thousands of years. Unlike many philosophical problems, it’s an easy one to describe. All of us have bodies, and all of us have minds. The mind-body problem is the problem of figuring out the relation between these two things. A bit more precisely, it’s the problem of figuring out the relation between states of that bodily organ called the brain and the workings of our minds.

For most philosophers, thinking about the mind-body problem is little more than an engaging pastime, but for nineteenth century scientists of the mind there was a lot at stake in solving it. These psychologists, psychiatrists, and neuroscientists wanted to find out what role brain processes play in explaining our experiences and behavior. And unlike most of today’s scientists, they were philosophically educated people who recognized the relevance of philosophy to their project.

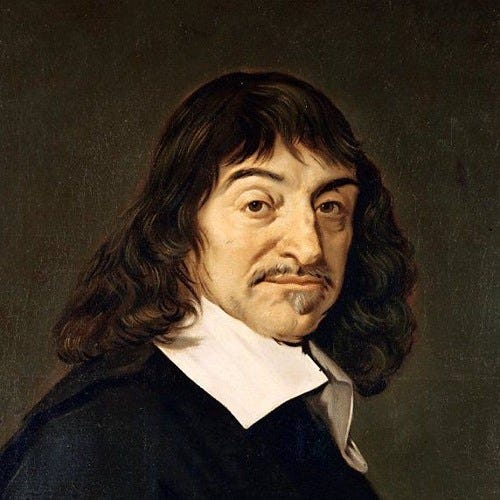

Many introductory texts on philosophy and the mind begin with the mind-body problem, because its been so important historically. More specifically, they often begin with a chapter discussing the views of the seventeenth-century French philosopher René Descartes, because he’s so closely associated with a take on the mind-body problem known as substance dualism.

The term “substance” might sound a bit weird, because in everyday vernacular substances are stuff like olive oil or toothpaste. But in traditional philosophy-speak, a substance is just a thing, and substance dualism is the view that there are two kinds of things in the universe, physical things and non-physical things. If you were a dualist and were taking inventory of every kind of thing in the universe, you might divide your list into two columns—one labelled “physical” and the other labelled “non-physical”—lots of everyday objects such as carrots, rocks, cars, and human bodies would fall under the first column. But the second column wouldn’t be blank. It might contain things like God, angels, ghosts and, importantly for this discussion, minds.

Descartes thought that people are compounds of bodies and minds, and that bodies and minds interacted with each other to produce experiences and behaviors. He didn’t invent dualism, but he formulated it clearly and argued for it in ways that seemed quite persuasive at the time.

Descartes’ brand of dualism had a lot of problems, but to very many people dualism seemed to be the only game in town. The world of subjective experience—of consciousness, feeling, and thought—just seemed so overwhelmingly different from physical states of a physical brain that it seemed crazy to deny that they take place in radically different metaphysical realms.

However, by the middle of the 19th century, dualism was coming under a lot of pressure from developments in the sciences. In particular, the emergence of the new discipline neuroscience seemed to challenge the assumption that the human brain and the human mind were two different (albeit interrelated) things. The challenge was especially acute in the sub-field of aphasiology, which investigated disturbances of language production or comprehension caused by damage to the brain. Ever since Descartes, our capacity for language had been held up as proof that the human mind just can’t be some part of the material world. But the 19th century aphasiologists were discovering that the language capacity is, at the very least, intimately bound up with that squishy globe of nerve tissue between our ears.

Even though scientific progress (not just in neurology, but also in biology and physics) was casting more and more doubt on the dualist assumption, most philosophers and scientists clung onto it for dear life. The alternative—that human minds just are human brains--seemed unthinkable. How could a purely physical thing, a living piece of meat, have hopes and dreams and thoughts and fears?

By the closing decades of the century, aphasiology had become a vibrant interdisciplinary nexus, comparable to cognitive science in the late twentieth century. It was, in the words of the neuroscientist Antonio Damasio, “the intellectual and practical center of neurology but also the focus for scientists and philosophers interested in the field that was to become psychology.”

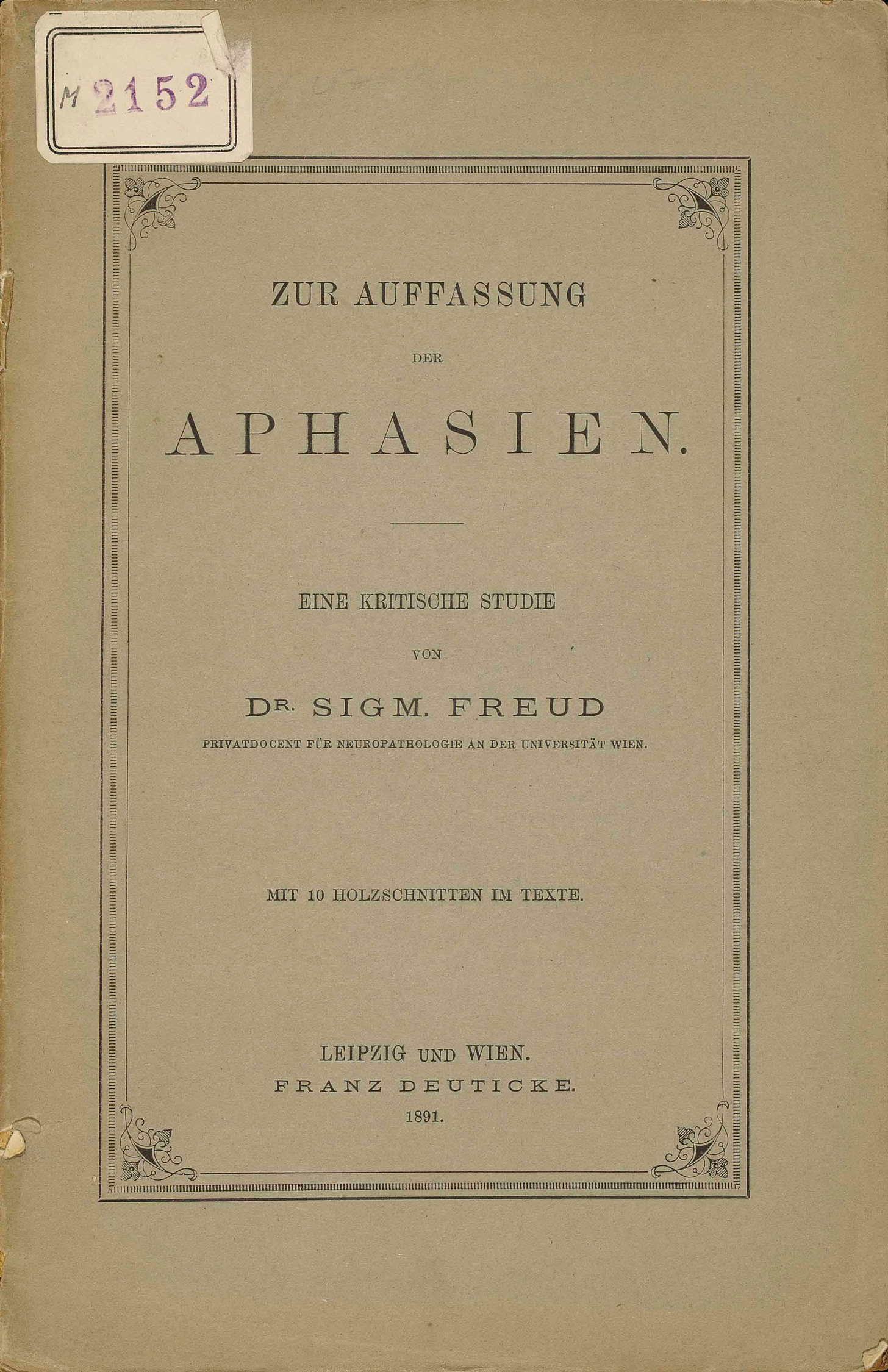

This is where Sigmund Freud entered the picture. Freud was trained as a neurologist, and included aphasiology among his particular research interests. As a young researcher, he even wrote a book about aphasia, which was published in 1891 and was highly regarded well into the twentieth century. Freud had almost certainly encountered the mind-body problem in the philosophy classes and readings from his university days, but the study of aphasia put it front and center for him.

Historians of psychology often say that early on, before inventing psychoanalysis, Freud adhered the mainstream view known as materialism, but later on rejected this in favor of the view that minds are distinct from brains. This couldn’t be more incorrect. A careful reading of late nineteenth century neuropsychological writings shows that, far from being hard-nosed materialists, most of Freud’s intellectual community were dualists. And a careful reading of Freud’s early neuroscientific works shows that Freud initially fell in with this orthodox position.

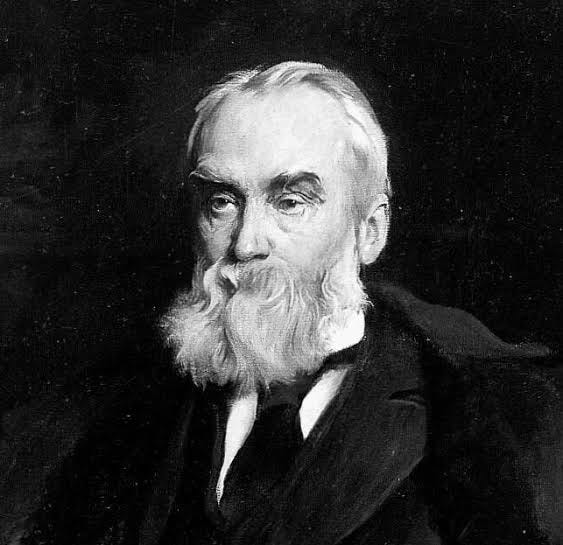

The writings of the important British neuroscientist John Hughlings Jackson—who was a major influence on Freud—are instructive. Like most scientists of his generation, Jackson was philosophically educated (sadly, that’s no longer the case for most scientists), and was alert to the philosophical implications of scientific discoveries. He recognized that Descartes version of dualism was inconsistent with the Law of the Conservation of Energy in physics—the principle that the quantity of energy in the universe remains constant—and therefore that Descartes’ theory had to be rejected. But like many other scientists of the day, he simply traded it in for a different version of substance dualism. Jackson opted for the theory known as “psychophysical parallelism”—the thesis, derived from the seventeenth century philosopher Gottfried Leibniz. It’s the weird idea that physical brains and non-physical minds don’t interact but merely run in parallel, precisely coordinated like two synchronized clocks. Jackson and others resorted to notions like this because the materialist alternative was just too challenging to seriously entertain.

There were emotionally-based reasons why materialism was hard to accept, too. Some thought that if the mind just is the brain, this implies that mental processes are wholly deterministic, and therefore that freedom of the will (and therefore moral responsibility) is illusory. Freud happily embraced the reality of what he called “psychical determinism,” and also recognized that this does not entail that free will does not exist. In philosophers’ jargon, he was what’s called a compatibilist.

Unlike most scientists of the mind during this period, who believed that mind and brain are two different things, Freud came to the conclusion that the mind is the brain, and cherished the hope that one day brain science would allow us to replace the psychological vocabulary that we use to interpret human behavior with an exhaustively neuroscientific one, a project that, he prophesied in 1908, would be on the agenda “a century from now.”