How to Misunderstand Dehumanization

Why the Psychological Literature on Dehumanization is a Mess

The illustration above is a seventeenth century print of blind monks examining an elephant. It illustrates the ancient Buddhist parable of the blind men and the elephant. Each of the monks has got a hold of one part of the elephant, and each mistakes the part for the whole.

When serious researchers disagree about an object of study, it’s sometimes because they’re situated just like these monks are. Each has got a piece of the truth, but mistakes their piece for the whole truth of which it is only a part. But the analogy can be misleading. Sometimes the researchers do not have a grasp of the parts a single elephant, but instead are holding on to a whole menagerie of different animals.

I was recently reminded of this parable when invited to contribute an article to a special issue of Current Research in Ecological and Social Psychology. It will appear in a special issue of the journal focussed on Painting an Integrated Portrait of Dehumanization. The editors describe the mission of the special issue as follows.

Dehumanization has accompanied many of our age’s darkest atrocities and continues to feature prominently in contemporary acts of discrimination and violence. This has inspired sustained scholarly attention, as social scientists have developed an abundance of distinct measures and conceptualizations of dehumanization over the past two decades. The proliferation of measures of dehumanization is both a marker of the success of the field and problematic, because the various ways in which dehumanization has been conceptualized have not been integrated into a coherent framework. Therefore, this special issue spotlights work employing a broad array of perspectives and measurement approaches to dehumanization. It aims to integrate these disparate conceptualizations of dehumanization into a coherent framework that sharpens our theoretical understanding of the construct.

I think that the project of synthesizing these various formulations of dehumanization is a fool’s errand. Dehumanization is a menagerie, not an elephant. Psychologists researching dehumanization don’t disagree because they’re addressing different components of a larger, more complex phenomenon. They disagree because they are addressing different phenomena entirely, misleading placed under the terminological umbrella of “dehumanization.”

In this essay I’ll explain why I hold this view, and also offer a couple more criticisms of mainstream theories of dehumanization.

But first, the back-story.

I initially became interested in dehumanization around 2005. It was perusing wartime visual propaganda sparked my interest. Looking at this material, a pattern became obvious; enemies are often pictured as subhuman animals—typically vermin, predators, or game animals.

I found this fascinating, and decided to delve what had been written about it. I was surprised to discover that at that time practically all of the research into dehumanization was being done by social psychologists. There was vanishingly little work on the subject in my home discipline of philosophy, and the same was true of next-door disciplines in the humanities.

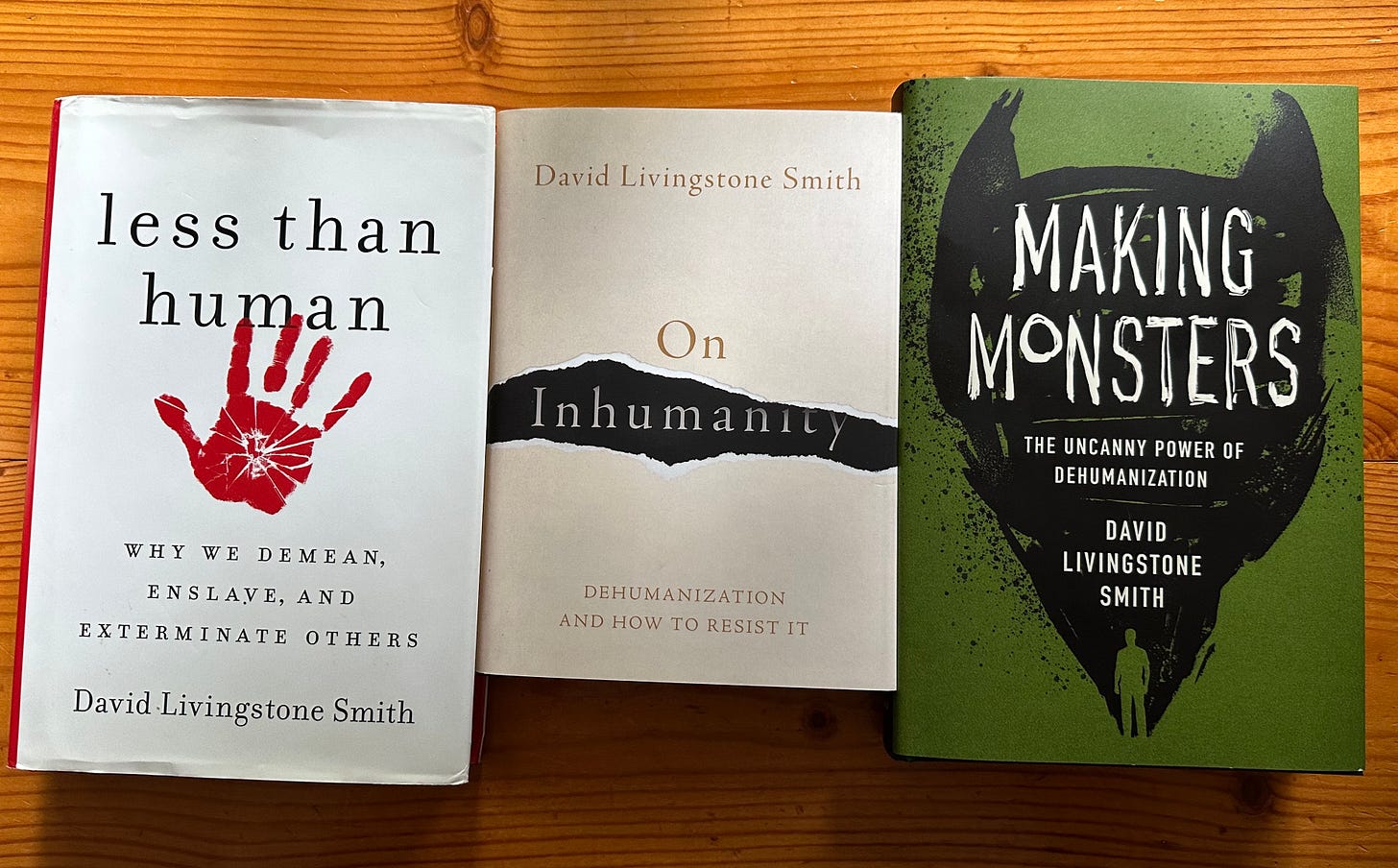

Prior to diving into the literature, I expected to find a great deal of interdisciplinary work on dehumanization, but I came up more or less empty-handed, with very few studies outside social psychology to draw upon. Clearly, this was a field needing urgently to be plowed. That’s why I decided to write my book Less Than Human: Why We Demean, Enslave and Exterminate Others, published in 2011. My views on dehumanization were altered and refined over the next decade of research. I set out the revised picture in On Inhumanity: Dehumanization and How to Resist It (2020), which was written for a very broad readership, and Making Monsters: The Uncanny Power of Dehumanization (2021), which is more academic (but still not boring!)

Anyone acquainted with my writing will know that I do not draw much on the social psychological literature. This might seem strange, given that this literature has blossomed over the past ten years or so, and is by far the richest scientific resource on dehumanization. But the fact is, I think that the social psychological paradigms are deeply flawed.

My contribution to the special issue mentioned above is called “Some conceptual deficits of psychological models of dehumanization.” It is available here.

When investigating a phenomenon, it’s crucial to make a distinction between conceptions and theories. A conception of a thing answers the question “What is it?” A theory answers the question “How does it work?” It’s obvious that conceptions have priority over theories: to figure out how a kind of thing works, we’ve go to first distinguish things of that kind from other kinds of things. Suppose you’re trying to figure out how cars work. You won’t be able to do this unless you can reliably distinguish cars from, say, bicycles.

But social psychological conceptions of dehumanization are all over them map. They pick out several distinct phenomena, and confusingly slap the label “dehumanization” onto each of them. As I put it in the article:

There are three main psychological conceptions dehumanization. Haslam's “dual model” has it that when people dehumanize others, they regard them as less human than others, and as either machine-like or animal-like. Waytz and Epley's “mind perception” model describes dehumanization as the failure to attribute mental states and processes to others, and thus regarding them as having diminished mental capacities (Waytz and Epley, 2012). Fiske's “stereotype content” model proposes that dehumanization is a function of attributions of interpersonal warmth and competence. This account “predicts that only extreme out-groups, groups that are both stereotypically hostile and stereotypically incompetent (low warmth, low competence), such as addicts and the homeless, will be dehumanized” (Harris and Fiske, 2006, 847)….Each of these ideas of what dehumanization is appears to be independent of the others. Even if there are substantial empirical overlaps between them, they are contending views of what dehumanization is, and as such logically exclude one another.

This is not a “blind men and the elephant” scenario. It’s not that each of these theorists have got a hold of part of a single something. Rather, each is addressing something entirely different, albeit loosely associated with the others.

So, how should we choose which conception of dehumanization to get behind?

One method is to use paradigmatic examples—examples all parties are likely to accept as instances of dehumanization. Nazi antisemitism is a good candidate. It strikes me—and I think that many others share my view—that if Nazi anti-semitic ideology is not an instance of dehumanization, than nothing is. I point out in the article that when tested against this example….

Waytz and Epley's mindlessness criterion falls at the first hurdle. The notion that Nazis regarded Jews as mentally deficient could not be more remote from the truth. Nazi ideologues regarded Jewish Untermenschen (subhumans) as fiendishly intelligent. As Adolf Eichmann stated in a recorded interview, Jews possess “the most cunning intellect of all the human intellects alive today” and are “intellectually superior to us” (quoted in Stagneth, 2014, 304).

And the other two mainstream accounts fare no better.

Haslam proposes that there are two forms of dehumanization. Dehumanization is either “mechanistic” or “animalistic.” We dehumanize others mechanistically when we think of them as lacking traits that distinguish animals (including human animals) from inanimate objects. We dehumanize them animalistically when we think of them as lacking traits that distinguish humans from other animals. With respect to the former, Nazis did not regard Jewish people as resembling inanimate objects….They are represented in Nazi propaganda as the very opposite: as sensuous, greedy, lustful beings. What about animalistic dehumanization? Given the Nazi picture of Jews as instinctually-driven, this seems like it should be a slam dunk. Haslam claims that animalistically dehumanized people are seen as “unintelligent, irrational, wild, amoral, unrefined, and coarse (Haslam, et al., 2006, 25). Nazi ideology often did represent Jewish people as wild, immoral and coarse, but not as unintelligent and irrational, and sometimes as overly refined cosmopolitans without roots in the Aryan values of blood and soil. At best, then, Haslam's model fits the Nazi case only imperfectly. Fiske's account also fails to cohere with Nazi antisemitism. According to Fiske, dehumanized people, “the lowest of the low” as she and Harris describe them, are seen as deficient in warmth (friendliness, trustworthiness) and competence (Harris and Fiske, 2006). Nazis certainly represented Jewish people as low in warmth—that is, as hostile and destructive—but equally certainly, they regarded them as hyper-competent, albeit in the service of evil ends.

The counter-argument that these conceptions do better at capturing other, uncontroversial examples (for instance, the dehumanization of African Americans) is unavailing. An acceptable notion of what dehumanization should be consistent with all such examples, not just a fraction of them.

A second objection that I raise in the article concerns theories, rather than conceptions, of dehumanization. Social psychological approaches home in on what goes on in people’s heads when they dehumanize others, but mostly pay scant attention to the social and political milieux in which dehumanizers dwell. For example, Nazi antisemitism is simply unintelligible unless one gives explanatory weight to centuries-long history of German antisemitic ideology, the particular social and economic conditions in Germany in the aftermath of the First World War, and Hitler’s rhetorical gifts. To do this effectively one must give a general account of how political forces impact on the human mind, including a theory of ideology and an analysis of propaganda. At best, mainstream psychological theorizing pays only lip service to these crucial issues.

My third and (for now) final objection concerns psychologists neglect of psychological theory when trying to explain dehumanization. Each of the three major accounts proposes that dehumanization comes in degrees. According to this story, attributions of humanness are “graded” (i.e., come in degrees). We regard others as human to the extent that they possess certain distinctively human traits, and subhuman to the extent that they lack them. This entails that when we dehumanize others we think of them as less human than ourselves, but not necessarily as less than human1.

I am very skeptical of this perspective. I believe that the weight of evidence suggests that attributing humanness is an all-or-nothing affair. People are either seen as human or as not, with no grey area in between. Furthermore, it’s clear that one can manifest all of the typically or even uniquely human attributes and yet still be regarded as less than human. Again, Nazi anti-Semitism provides a good illustration: no matter how human Jewish people appeared on the “outside”—no matter how many human traits they displayed—they were nonetheless regarded as essentially subhuman.

The disjunction between appearance and reality—between how people seem and what they really are is, in my view indispensable for making sense of the phenomenology dehumanization. I’ve argued at length in my books and articles that the absolute distinction between the categories “human” and “subhuman” is scientifically underwritten by the now immense literature on psychological essentialism, and it is this essentialist bias that explains why dehumanization is so intimately tied to race (yet another topic that is largely neglected in the social psychological corpus).

I think that my own conception of dehumanization, and my detailed causal theory of how dehumanization works, both psychologically and ideologically, succeeds in surmounting all of these difficulties. But of course, I’m biased. This is something that’s up to you, and the future, to decide.

Another shortcoming of the social psychological accounts is that they don’t address the implicitly hierarchical nature of dehumanization. There is an important explanatory distinction between a quantitative notion of possessing a greater of fewer number of “human” attributes, and the normative notions of superiority and inferiority that must be at the core of any adequate analysis of dehumanization.

![враг рода человеческого [Arch-enemy] враг рода человеческого [Arch-enemy]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!dLmx!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fc29b5319-c253-4770-bd1e-47448cc254d4_1478x2000.jpeg)