The evocative term “soul murder” was popularized by the America psychoanalyst Leonard Shengold, who used it to describe the devastating psychological consequences of severe forms of childhood abuse and neglect. But Shengold did not invent the term. He got it from the 1903 book Memoirs of My Nervous Illness (Denkwürdigkeiten eines Nervenkranken), written by Daniel Paul Schreber, a schizophrenic German judge. Like the psychiatrists Morton Schatzman and Zvi Lothane, who also wrote about Schreber and soul murder, Shengold would probably never have encountered the term were it not for Freud’s analysis of Schreber’s memoir, published in 1911 as “Notes upon an autobiographical account of a case of paranoia (dementia paranoides).”

During the early 19th century, the crime of “soul murder” was recognized in the legal code of Saxony, and the legal scholar Paul Johann Anselm Ritter von Feuerbach tried unsuccessfully to have it included in Bavarian law. Half a century later, American abolitionist and sufferagist Paulina Wright Davis alluded to the legal meaning of “soul murder” at the National Woman's Rights Convention in 1870 when she spoke of the “long history of the despotism of repression, which German jurists call 'soul murder'; an unwritten code, universal and cruel…and so subtle that, entering everywhere, they weigh most heavily where least seen." Its next appearance was in August Strindberg 1887 essay on Henrik Ibsen’s play Romersholm and later used by Ibsen himself in the 1896 play John Gabriel Borkman. Strindberg used it to describe the act of depriving a person of their love of life.

Facts about the provenance of “soul murder” that I’ve chronicled above are easy to discover. But there is a much earlier use of the term by the 17th century English cleric Morgan Godwyn that has so far gone unnoticed.

Godwyn was an Anglican clergyman, who studied at Christ Church College, Oxford, with John Locke. He graduated in 1665, and after briefly serving as a chaplain during the Dutch war, sailed to Virginia. He left for Barbados in about 1670, and returned to England approximately ten years later.

Godwyn’s mission in Virginia and Barbados was to baptize Indians and enslaved Africans. During the late 17th century this was dangerous path to tread. Vast profits were being raked in through the exploitation of slave labor. This included profits accrued by the King, Charles II, and his brother James (later King James II) who were in effect the CEOs of English transatlantic slavery, and were also beneficiaries of the tax revenue from goods such as sugar and tobacco produced by enslaved people in the Caribbean and North American colonies.

The issue of baptism was entangled with another factor: the dehumanization of enslaved people. Only those possessing human souls could be Christians, hence it was attractive those who profited from transatlantic slavery to deny that enslaved people possessed human souls (a similar scenario to one played out a century earlier in the debate between Las Casas and Sepúlveda about whether it was permissible for to enslave the indigenous peoples of the Spanish empire).

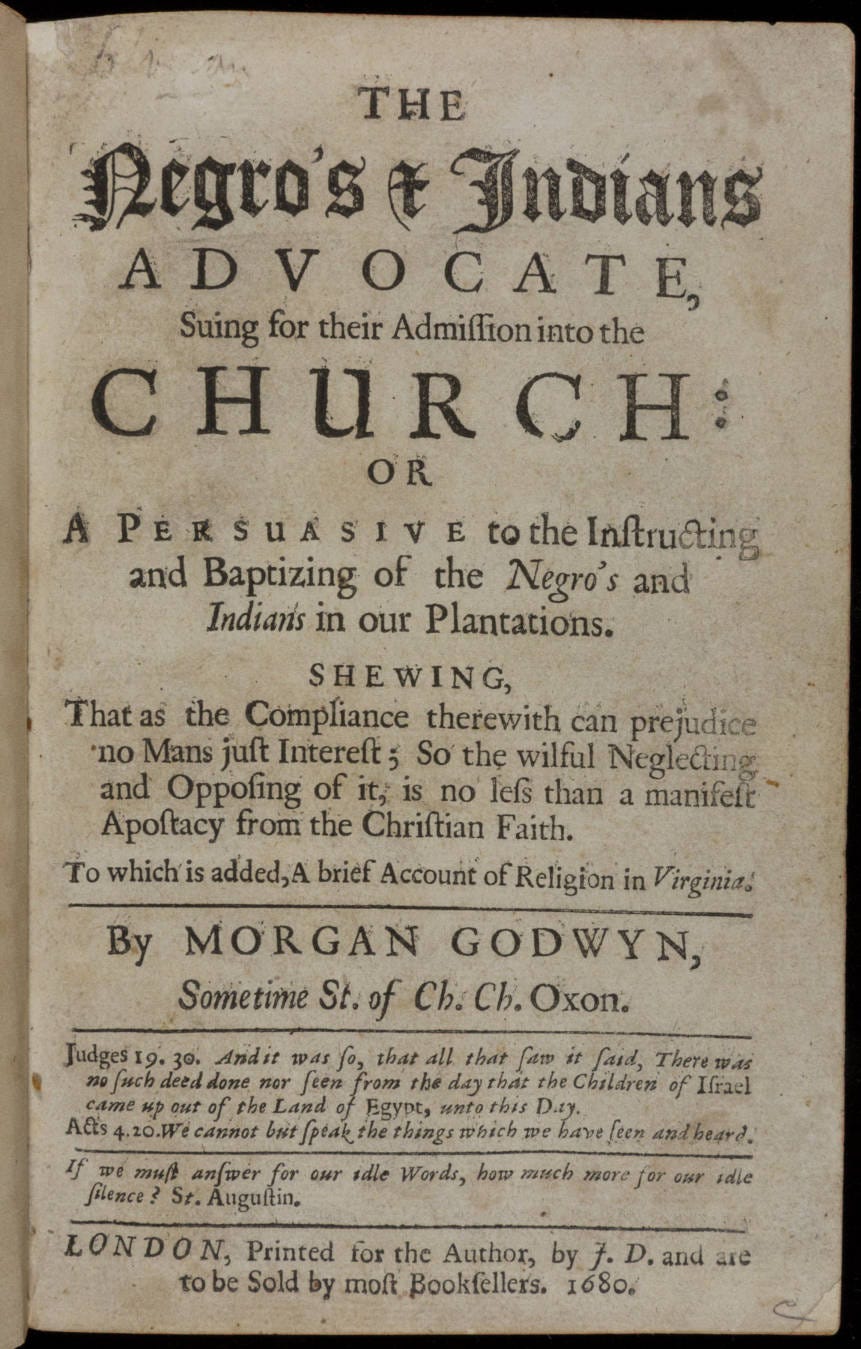

Godwyn’s first book, published in 1680, was titled The Negro’s and Indian’s Advocate. In it, he insists that Black people are human, “because he is endued with a reasonable and immortal Soul, which alone constitutes him a Man” Hence, Black and White people are not fundamentally different.

Herein doth also concur every Man's Sense and Judgment touching other Creatures, nothing doubted (tho Black) to be of the same species, with the Whiter: As is seen of Birds, which do often differ much in the Feather, yet nevertheless are one and the same in kind.

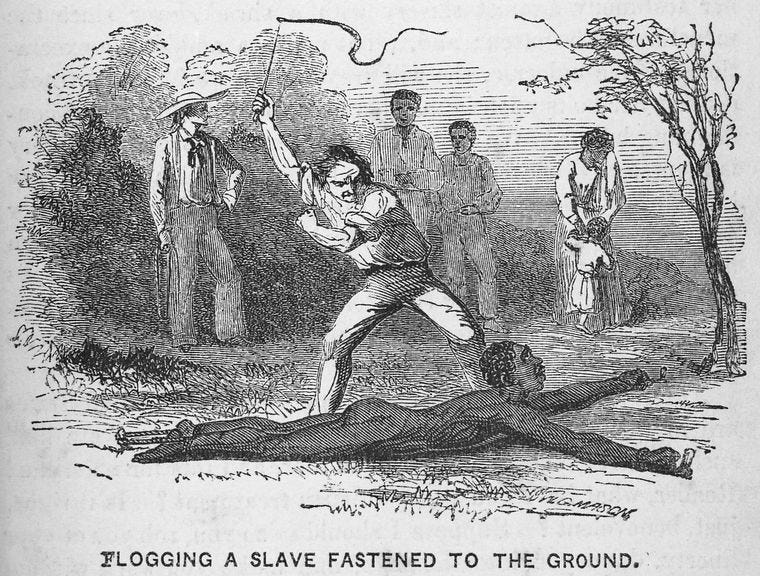

However, he points out, the advocates of slavery deny Africans’ humanity. To justify slavery, “the poor African must be Unman'd and Unsoul'd; accounted, and even ranked with Brutes.” It is in this context that Godwyn introduces the term “soul murder” as a synonym for what is nowadays called “dehumanization,” and details how dehumanization fosters atrocities.

Nor to speak truth, without that of their Negro's brutality, do I see how those other Inhumanities, as their Emasculating and Beheading them, their croping off their Ears (which they usually cause the Wretches to broyl, and then compel to eat them themselves); their Amputations of Legs, and even Dissecting them alive; (this last I cannot say was ever practised, but has been certainly affirmed by some of them, as no less allowable than to a Beast, of which they did not in the least doubt but it was justifiable). Add to this their scant allowance for Clothes, as well as Diet, and (which is often the calamity of the most Innocent and Labourious) their no less working than starving them to Death; all which could never otherwise be so glibly swallowed by them, but upon a persuasion of this, or of the former worse Principle. Both without doubt contrived in Hell, receiving their first impressions in no other than the Devil's Mint, purposely designed for the murthering of Souls.

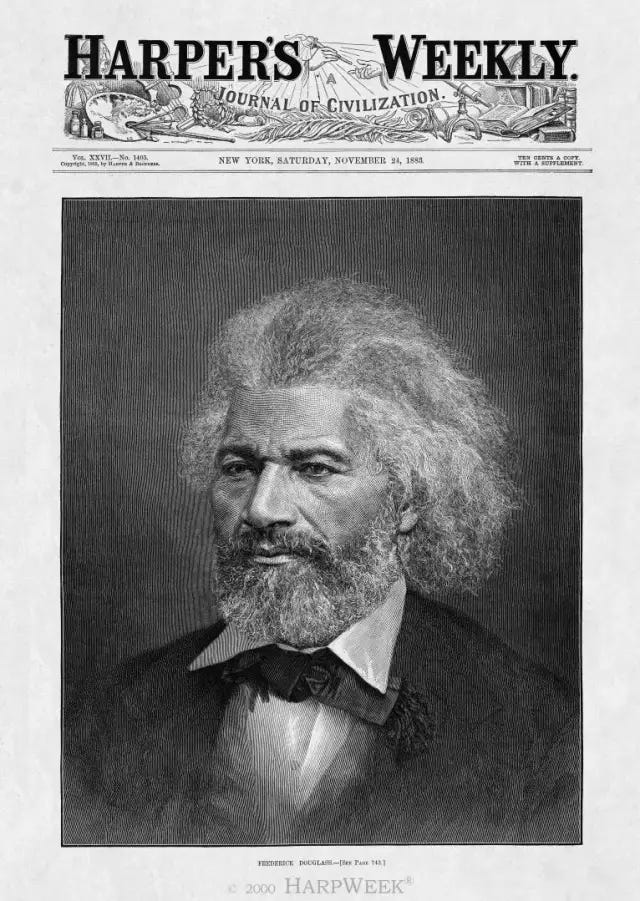

Most scholars think of Godwyn as a proto-abolitionist: a man who did not object to slavery as such, but who railed against the abuse of enslaved people. Frederick Douglass was one such interpreter. On April 16, 1883, speaking to a predominantly African American audience, Douglass described The Negro’s and Indians Advocate as “a literary curiosity and an ethical wonder…. the starting point, the foundation of all the grand concession yet made to the claims, the character, the manhood and the dignity of the Negro.” He made the point that, two hundred years earlier, when Godwyn published his tract, White Christians believed that baptism “could only be properly administered to free and responsible agents, men, who, in all matters of moral conduct, could exercise the sacred right of choice,” but “plainly enough, the Negro did not answer that description. The law of the land did not even know him as a person. He was simply a piece of property, an article of merchandise, marked and branded as such, and no more fitted to be admitted to the fellowship of the saints than horse, sheep or swine.”

Despite his acknowledgement that “In the eyes of the wise and prudent of his times, Dr. Godwin was a dangerous man” and that in “the common law at that time, baptism was made a sufficient basis for a legal claim for emancipation,” Douglas took Godwyn’s explicit claim at face value that he was not opposed to slavery per se.

In contrast, historian Holly Brewer argues in her article “The mysterious disappearance of Morgan Godwyn,” that he wanted to expose and condemn slavery, while also protecting himself from the heavy hand of the state. In support of this view, she sites Roger L’Estrange’s remark in 1663 that “they that write in fear of a law, are forc’d to cover their meaning under Ambiguities and Hints.” She writes, expanding on this point, that Godwyn “shrouded his arguments, particularly at the beginning of each of his four published works, with words that hid their radicalism, that sought to placate the censors (of the press) with reassurances that he would not challenge slavery….Godwyn practiced the fine art of subversion by dissimulation, as he had to do to get anything published and to avoid prosecution for sedition or treason.”

Godwyn had to walk a tightrope, precariously strung between speaking truth to power and plausible deniability because attacking slavery was tantamount to defying and morally condemning the monarchy of the day. Brewer notes:

Since the enslavement of Africans was royal policy, criticizing slavery could be considered sedition or even treason, depending on how explicitly one condemned the king’s or the king’s brother’s actions. Charles II and his brother James put the weight of their legitimacy behind creating slavery in their empire. From the restoration in 1660 (starting that October, months after he regained his crown) Charles II set up the first incarnation of what would later be called the Royal African Company, and gave it monopoly power over the slave trade. He made his brother James its Governor. Charles II consolidated the English ability—but particularly the Royal family’s ability—to engage profitably in the slave trade and to supply their plantations with slaves.

Morgan Godwyn seems to have coined the term “soul murder,” but what did he mean by it? There were two components which to his mind went hand in hand. One was strictly religious. He believed that denying Black people admission to the church consigned their souls to the terrible fate of hell. The other—bound up with the first—was the act of denying that African people had souls. This second sense of “soul murder” is equivalent to what is now called “dehumanization.” The word “dehumanization” was not available in the year 1680. It was only introduced into the English language during the 19th century (Lincoln’s assertion that Stephen Douglas “dishumanized” African Americans is an early instance), but the idea that some people think of other people as subhuman creatures was clearly central to Godwyn’s thinking.

Godwyn’s writings are replete with examples of soul murder as dehumanization. He reported being told that to a slave, baptism was “no more beneficial, than to her black bitch.” Historian Rebecca Ann Goetz explains in her book The Baptism of Early Virginia; How Christianity Created Race, “Applying bestial characteristics to African slaves was a convenient mechanism for Virgina planters to protect their property from baptism—after all, dogs could not be baptized….” Indeed, Godwyn referred to enslaved people being “unsoul’d and unman’d.” He unambiguously asserted that slaveholders “infer their Negro’s Brutality; justifie their reduction of them under bondage…and upon a sudden (with greater speed and cunning than even the nimblest juggler or witch1) transmute them into whatever substance the exigence of their wild reasonings shall drive them to.” He testified that colonists embraced the “disingenuous position” “the Negros, though in their Figure they carry some resemblances of Manhood, they are indeed no men,” and that they advocated “Hellish Principles, vis. that Negroes are creatures destitute of Souls, to be ranked among the Brute Beasts.”

Early in 1685, shortly before Charles II’s death and James II’s succession, Godwyn threw caution to the winds. In a sermon initially delivered in Westminster Abbey, and then repeated elsewhere in London—a sermon with soul murder as its centerpiece.

“We have, as it were conspired with Satan,” he told the congregation, “and entered into a confederacy with Hell it self, . . . We have exceeded the worst of Infidels, by our first enslaving, and then murthering of Mens Souls.” Arguing that all Englishmen are complicit, and turn a blind eye to the atrocities being committed in the colonies, he said “Whilst those abroade are thus acting and carrying on their Butcheries upon the Souls of Men there, how quietly and unconcernedly in the mean time do we sit down here, and take our ease, not once in our thoughts reflecting upon this Calamity.”

Wherefore, since God hath signed this eternal Precept of Blood for Blood, and hath as it were sworn, That he will require the Blood of our Lives, at the Hand of every Man's Brother; yea, and of the very Beasts too;* and hath also in several places no less positively declared, That no satisfaction shall be accepted for the Life of a Murtherer; and that a Land defiled with Blood, cannot be cleansed of it, but by the Blood of him that did shed it; all which is to be referred only to the Body: What Punishment can we suppose answerable to this so much more horrid Crime of murthering of Souls? If Blood for Blood, and Life for Life must go for the one, certainly then Soul for Soul here, is the least that can be required.

Godwyn was all-too-aware aware that speaking out placed him in grave danger. And yet, after preaching this sermon in London, he repeated it elsewhere in England, and even had it published under the title Trade preferr'd before religion and Christ made to give place to Mammon represented in a sermon relating to the plantations: first preached at Westminster-Abbey and afterwards in divers churches in London. As Brewer summarizes:

“For that I have, as it were, put my Life in my hand,” he wrote in the introduction to his sermon, his last surviving text. He felt called, finally, “to oppose those . . who do not cease to pervert the right ways of the Lord…[to speak out] when no body else either durst [dares] or would.” He was willing to become “A fool for Christ’s sake, and conceived that it might better be done by me, than not at all.” He knew that speaking out was suicidal—many told him so—but “I could no longer be silent. . .My heart grew hot within me, and the fire was kindled; and at the last I spake with my Tongue, declaring from the pulpit, as oft as I had opportunity, what I have now delivered from the Press.”

James was crowned king in late April 1685 in Westminster Abbey—the very place where Godwyn had delivered his blistering jeremiad less than two months before the coronation (the text of which was published just over a month later). Brewer suggests that he paid dearly for his candor. “Remember,” she writes, “that…the new King, personally controlled the slave trade.”

James was governor of the Royal African Company (and had been since the inception of the royal monopoly in 1660). Giving and especially publishing this sermon was a profoundly political act. It was sharply critical of the new King's longstanding actions and of all that he legally legitimated and enabled in the new world…. After that Godwyn vanishes from the historical record. He disappeared during the same month—June 1685-- that Monmouth's rebellion against James II both began and ended in the west country. James II afterwards had some 2600 of the participants in that uprising prosecuted in vast trials, presided over by Judges George Jeffries and four other common law judges who held their seats “at his pleasure” meaning he could dismiss them without cause. Jeffries, whom he afterwards promoted to Lord Chancellor, became known in popular legend as the “hanging judge” and these trials as “the bloody assizes.” The trials went on for months, their outcomes publicized in broadsides that listed the executed: On the 18 & 19 of September alone at Taunton castle, 144 were sentenced to be hanged, drawn and quartered (that is they had their guts pulled out and their limbs severed while alive) or burned alive for a total, by one contemporary listing which gave the names by village, of 593 executions. Jeffries condemned at least 900 others to bond servitude in Barbados and some of the remainder to the whip.

We cannot be certain, but it is overwhelmingly likely that Morgan Godwyn paid the ultimate price for his opposition to soul murder—that he was tried, perhaps tortured, and executed for sedition. He deserves recognition and admiration as an early theorist of racial dehumanization, and a campaigner against the horrors that come in its wake.

This prefigures the Barbara J. Fields’ and Karen E. Fields’ notion of “racecraft” as described in their book Racecraft: The Soul of Inequality in American Life.