Killing

Why the act of killing is at the heart of both morality and dehumanization

As I write this, the United States is reeling from yet another mass shooting. This time, a man armed with a high-powered weapon strode into a Texas shopping center and mowed down eight people, including three children. His vest was decorated with the letters RWDS, standing for Right Wing Death Squad, an acronym that is increasingly popular among White supremacists. The carnage only ended when he was shot dead by a police officer. According to the Guardian newspaper:

Police have identified the gunman in the shooting as Mauricio Garcia, a 33-year-old whose activity on a Russian social networking site reveals a fascination with white supremacy and mass shootings, which he described as sport. Photos he posted showed large Nazi tattoos on his arm and torso, including a swastika and the SS lightning bolt logo of Hitler’s paramilitary forces.

There must be very few Americans who were not horrified by this event and others like it. Ask a random person “What’s the worst thing that anyone can do?” and you will likely be told “Killing others.” Press them further by asking about particular kinds of killing, their attitude toward killing in self-defense, killing in warfare, euthanasia, abortion, and capital punishment, and the responses will be more varied. It is rare for people to object to killing others tout court. The worst thing that anyone can do is to kill illegitimately, that is, commit an act of murder.

The idea that some kinds of killing are legitimate but others are not is rooted in cultural and religious traditions. The specific criteria vary from culture to culture, and from time to time.

The Bible is full of accounts of legitimate killing, including killing at the deity’s behest. Theologian Raymond Schwager points out in his book Must There Be Scapegoats? Violence and Redemption in the Bible, that:

The passages are numerous where God explicitly commands someone to kill. Aside from the approximately one thousand verses in which Yahweh himself appears as the direct executioner of violent punishments, and the many texts in which the Lord delivers the criminal to the punisher’s sword, in over one hundred other passages Yahweh expressly gives the command to kill people. These passages do not have God himself do the killing; he keeps somewhat aloof. Yet it is he who gives the order to destroy human life.

These include injunctions to commit genocide (“…do not leave alive anything that breaths. Completely destroy them…as the Lord your God has commanded you”1 ) and the celebration of infanticide (“Happy is he who repays you for what you have done to us – he who seizes your infants and dashes them against the rocks”2)

These considerations invite a raft of questions. Why is it that the distinction between legitimate and illegitimate killing is found in every human society? Why are some kinds of killing deemed legitimate, excusable, or even obligatory and others regarded as the ultimate moral offense? Why do all human societies everywhere and as far as is known at all times strictly regulate the act of killing? And bound up with these, why is dehumanization such an effective tool for overcoming our resistances to killing?

I have explored these questions in my most recent books On Inhumanity: Dehumanization and How to Resist It and Making Monsters: The Uncanny Power of Dehumanization. Here, I want to pull together some of the main strands of my argument, and add a little bit more that’s new.

Homo sapiens are the most social of mammals. No other mammalian species comes anywhere near to our extraordinary level of gregariousness. It is a truism that social animals must suppress aggression within their communities. It follows that all social animals must be equipped with mechanisms with the function of regulating aggression against fellow community members, whether learned or in some sense innate.

Sociality depends on the existence and effectiveness of such mechanisms. In some social animals, such as ants, they operate by producing and consuming chemical signals. Fellow colony-members are stamped with an olfactory passport that protects them aggression, and distinguishes them from outsiders that can be killed. In other social animals, such as chimpanzees, cognitive mechanisms involving memory and recognition do the same job.

Obviously, we’re more like chimpanzees than we are like ants. But we’re even more like bonobos.

A chimpanzee community, where aggression is inhibited, is just the local breeding group. But outsiders are fair game for lethal violence. Brian Hare and Vanessa Woods write in Survival of the Frendliest: Understanding Our Origins and Rediscovering Our Common Humanity that, in stark contrast to their chimpanzee cousins, “neighboring groups of bonobos are just as likely to travel together, share food, and interact amicably, as to show any hostility.” Like bonobos, human beings cooperate between groups, not just within them. Archeological evidence shows that early human groups engaged in trade relations, sometimes over long distances, hundreds of thousands of years ago.

Rivers of ink have flowed in speculations about the evolutionary foundation for why chimps and bonobos behave so differently, as well as well as speculations about the behavioral continuity or discontinuity between these species and are own. Those who think that human nature is more akin to chimpanzee nature would baulk at my claim that we are most similar to bonobos. To see why, consider these remarks from the same passage by Hare and Woods that I cited in the preceding paragraph. Unlike chimpanzees, they write:

No male bonobo has ever been seen to kill a baby. Male bonobos do not form gangs to patrol their border or commit lethal aggression against their neighbors. No bonobo in captivity or in the wild has ever been observed to kill another bonobo.

Of course, we Homo sapiens do all these things too, and we also perpetrate acts that are far worse. So, anyone studying human aggression is confronted with what seems to be a paradox: we are an ultrasocial species equipped with powerful inhibitions against violence that also commits acts of violence that are unparalleled in their cruelty and destructiveness.

This seeming paradox is not difficult to unravel. As ultrasocial primates, we’re inclined to cooperate with other members of our species and to inhibit aggression against them. But as big-brained primates that are capable of sophisticated instrumental thinking, we are also able to recognize that acts of violence can be advantageous to ourselves and our immediate community. By exterminating or enslaving our neighbors we can appropriate their resources and exploit their labor for our own advantage.

But a question remains: how do we manage to overcome the inhibitions against violence that are central to human life? Here it is culture that does the heavy lifting. Over the millennia, we have crated cultural practices that have the function of selectively disabling inhibitions against same-species violence. We have culturally engineered ourselves to be capable of performing acts that would otherwise be very difficult, or even impossible, for most of us to do.

The use of psychotropic drugs, including alcohol, is one such technique (see, for example, Edward B. Westermann’s book Drunk on Genocide: Alcohol and Mass Murder in Nazi Germany, which describes the use of alcohol as a lubricant for atrocity in meticulous detail). The use of mind-altering rituals, often with rhythmic chanting and drumming, to prepare men for battle is another. Dehumanization is a third, very potent tool. It has the power to liberate (and also fuel) violence precisely because of the force of the idea that killing other humans is wrong, but if the victim is subhuman, then the act of killing is not an act of murder.

All this raises two further questions. What exactly does it mean to say that some beings are subhuman? And why does regarding others as less than human legitimate harming them?

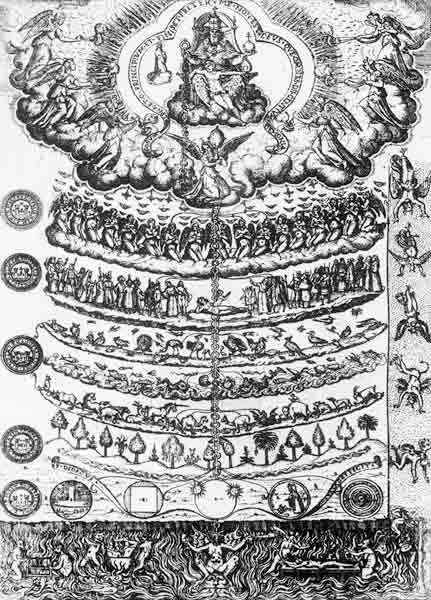

With regard to the first question, the notion of subhumanity implies a background notion of hierarchy—the idea that some kinds of beings are in some sense “higher” or “lower” than others. This framework is not merely descriptive. It is heavily normative, and immense carries moral heft. The higher we rank a being, the greater intrinsic value we endow it with. And conversely, he lower we situate a being on the scale, the less its life matters, and the freer we are to use it as we will—for amusement, for labor, for sport, for food.

Historians call this conception of the universe the Great Chain of Being. Arthur O. Lovejoy, who authored the main text on this subject, described the Great Chain as a model that began its career in Greco-Roman antiquity, persisted for centuries, and then disappeared towards the end of the 18th century. But this isn’t true. The hierarchical conception of the cosmos, although not universal, is vastly more ancient and pervasive than Lovejoy would have it. And it has not vanished in the wake of the growth of the scientific image of the biosphere (it’s still acceptable to swat a fly because it’s “just a fly”). Notions of hierarchy continue to infuse the way we conceive our place in the natural world, and our relationships with other kinds of organisms, even when we reject them intellectually.

Now, on to the second question.

Here is a fact about animal existence: life feeds upon life. To survive, animals must kill or dismember other living things. Even herbivores do violence to the plants that they consume, a point that’s been made all the more poignant by the recent discovery that plants “scream” when they are injured. Only frugivores are exempt from nature’s cycle of violence and destruction.

Unlike other animals, we humans are able and driven to reflect on our behavior, and thereby fashion reasons to justify it. Our very existence—our profoundly social existence—demands that we make a moral distinction between ourselves and those other organisms that we kill and exploit.

I call this “the problem of killing.”

I think that the idea of the Great Chain of Being got traction and has been so robust, because it provides a solution to the problem of killing, and also provides the basis for exterminating other human beings through the process of dehumanization. The lower a creature is on the hierarchy, the less its life matters and therefore the more killable it is. Dehumanization licenses atrocity and mass murder precisely because it demotes other members of our species to the status of subhumans.

Deuteronomy 20:16

Psalm 137: 9

Yes.. this is so vital to our understanding of human nature and how people cope with killing living things - and, ultimately how they cope with executing other humans when they feel that these are “not human”. When I was in the Kalahari, I eventually asked Ragai, a Kua “healer”, to tell stories - essentially origin myths - to the crowd assembled for a dinner in my camp. One of the stories he told was truly amazing as it contained elements of similar stories that Megan Biesele had collected almost a thousand miles away from San speaking other languages. These myths concerned the fate of wives in inter-species marriages, for example. In Ragai’s telling, it was “the buffalo wife” and Megan recorded it as “the elephant wife” but both stories seemed to emphasize the sacred circle of life that demanded reverence for the sacred kinship between living things, and stipulated a prayer of thanks for the role of the one killed - a prayer that indicated that the spirits of the killed and the killer would eventually be reunited in another dimension after death. My recounting his here: https://anthroecologycom.wordpress.com/2018/06/12/when-the-sacred-circle-is-broken/ and I also did it for a recording here at the evening seminar at the Anthropology department in the University College London: https://vimeo.com/703668006

Megan then was asked to do a followup talk, which was recorded too: https://vimeo.com/776639178