One of the core elements of my theory of dehumanization is what I call the problem of killing. Killing has a special moral significance. Ask anyone what they consider to be the most morally heinous act, and they are likely to point to the act of killing.

As far as we know, people everywhere and at all times have considered killing as morally special. In many cultures, the act of killing another person in battle was supposed to contaminate the killer, who was required to undergo rituals of purification before reentering society. And as far as we know, people everywhere and at all times have cared for their dead.

This is not to say that killing others is banned in all circumstances. The person who cites killing as the supremely morally egregious act is likely to accept that killing is not wrong in all circumstances. They might, for instance, believe that it’s acceptable to take the lives of others in just war or self-defense, to execute criminals, or to abort fetuses. But allowable killing is strictly constrained by social rules, whether codified or not. Violations of such rules are punishable, sometimes by death.

Notice that the strict taboo applies only, or almost only, to human beings. Taking the lives of other organisms is generally regarded nowhere near as grave as taking human life. Even those who are horrified at the slaughter of pigs and cattle mostly regard their lives as mattering less than human lives do. Only the most devout Buddhists object to killing insects, and virtually no one has a problem with killing fungi, plants, and bacteria.

For millennia the byproducts of slaughtered animals such as fur and bone have been crucial to human ways of life. We kill other animals not only for food and animal byproducts, but also for protection from predation, and as a consequence of clearing land for agriculture. We also kill plants, although we do not usually think of harvesting vegetables as an act of killing. Homo sapiens cannot subsist on a diet of leaves and fruit. We must kill. As Allen et al. remark in their article “Why humans kill animals and why we cannot avoid it,”

Achieving a no-killing lifestyle is a physical and ecological impossibility because all lifestyles are dependent on multiple forms of accidental or purposeful, indirect or direct, animal killing. For instance, most vegetable and leguminous foods come from crops that are grown on land where animals have been killed or displaced during or have died subsequent to agricultural intervention. Because one cannot kill that which has already been killed, a contemporary no-killing lifestyle might be more accurately termed a post-killing lifestyle.

As human beings, we look for justifications for what we do and what we refrain from doing. What is it that makes some organisms killable and others not? Why is it deemed acceptable to slaughter a pig, or roast a cauliflower, but not to murder your neighbor?

Over time, we have found several ways to grapple with the problem of killing. I’ll discuss three of them here. But first I need to touch on why the taboo on killing humans is so weighty and pervasive, transhistorically and transculturally.

We Homo sapiens are ultrasocial animals. In fact, there is no other mammal that is as intensely social as we are. For most social animals, sociality is confined to the local breeding group, but this is not the case for us. Archeological evidence suggests that humans have been part of far-flung cooperative networks for tens of thousands (maybe hundreds of thousands) of years.

One solution to the problem of killing, found among hunter-gather societies, denies any fundamental distinction between people and animals. For convenience sake, I will call this the “egalitarian solution.”

The egalitarian solution sounds paradoxical. How can a line be drawn between the conditions under which Homo sapiens can be killed and other species can be killed if animals are people? The appearance of contradiction is dispelled by the idea that hunting is a cooperative enterprise between (human) predator and (non-human) prey. As Robert Brightman describes in his book Grateful Prey: Rock Cree Human-Animal Relationships:

The event of killing an animal is not represented as an accident or a contest but as the result of a deliberate decision of the animal or another being to permit the killing to occur. The dream events that Crees say prefigure successful kills are sometimes talked about as signs that this permission has been given. In waking experience, the decision finds culmination when the animal enters a trap or exhibits its body to the hunter for a killing shot. Since the soul survives the killing to be reborn or regenerated, the animal does not fear or resent the death….[T]he role of the hunter-eater is not that of passive recipient only, and the animals themselves stand to gain from the exchange. Having received the gift of the animal's body, the hunter reciprocates. Animal souls are conceived to participate as honored guests at feasts where food, speeches, music, tobacco, and manufactured goods are generously given over to them.

In short, the prey animal wants to be killed and benefits from being killed, so killing is an act of reciprocity rather than an act of violence.

This kind of solution may have been common prior to the advent of agriculture, in foraging societies without rigid patterns of social stratification. It’s understandable that such societies would also adopt an egalitarian attitude towards other animals, and given that such societies require animals as a protein source, it’s only natural that they would adopt the view that prey offer themselves to the hunter, in a dance of give and take.

I think it likely (although admittedly speculative) that this attitude changed with the advent of agriculture and the domestication of livestock. Anthropologists tell us that rigid patterns of social stratification emerged with agriculture. People were socially ranked on a hierarchy, with the ruler or ruling class at the top and laborers or slaves at the bottom. We can see this sort of stratification very clearly in the social structure of bronze age civilizations like that of ancient Egypt, where the pharaohs were deified.

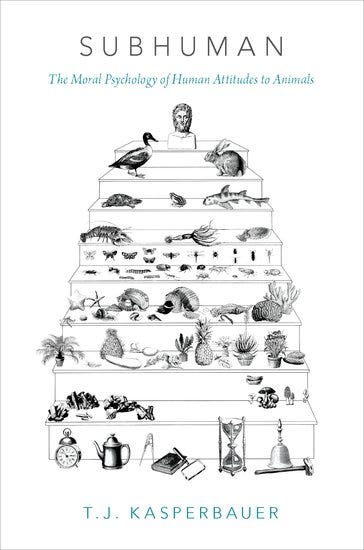

Perhaps it was when we transitioned from foraging to agriculture that we also transitioned to a different solution to the problem of killing. We began to project hierarchies onto the cosmos. Just as the social order was divided between the rulers and the ruled, the cosmos itself was divided between gods, humans, and lesser, nonhuman beings. Over time, this metaphysical framework expanded into an elaborate ideology known as the Great Chain of Being.1 I’ll call it the “hierarchical solution.”

The hierarchical solution assigns every kind of being to a rank. In Christian versions of it, like the one illustrated above, God is at the top, followed by archangels, angels, humans, various strata of animals, plants, and lifeless minerals at the bottom (demons are beneath the Chain, rather than on it because they are deviant, unnatural beings). The higher a being is ranked, the greater its intrinsic value (the value that it has in and of itself). Anything ranked below the human is literally subhuman, of lesser value than human beings, and can be treated accordingly.

Unlike the egalitarian solution embraced by the Cree, the hierarchical solution draws a sharp distinction between humans and other “lower” organisms. Animals, like plants, belong to a lesser order of being, and can be killed and exploited with impunity. And even though religious ideas infuse many versions of this ideology, it is also compatible with a secular, humanistic outlook (ever since the death of God, we have placed ourselves at the apex of the hierarchy). Thousands of years after its probable inception, and despite the fact that it does not enjoy scientific support, the hierarchical picture of the biosphere is still firmly cemented into our moral psychology: it’s OK to swat a mosquito because it’s just a mosquito, or boil a cabbage because it’s just a cabbage.

The hierarchical paradigm also makes dehumanization possible and thereby facilitates violence against other human beings. Dehumanization requires hierarchy because dehumanized people are ranked as less than human. Scroll up to the photograph at the start of this essay. It’s a photograph of the lynching of an African American man named Henry Smith. Smith was accused of raping and murdering a child. He was arrested, tortured, and then burned alive before an eager audience of thousands of men, women, and children. Smith, like other African American men, was described in the press of the day as a subhuman creature, a beast in human form. This way of thinking is only possible within a framework that elevates human beings above all other creatures.

A third approach to the problem of killing proposes that it is unacceptable to kill or otherwise harm sentient beings because they suffer, and the infliction of suffering is morally wrong.2 Call this the “empathic approach” to the problem of killing (for want of a better term). Many, perhaps all, animals are sentient, so it is wrong to kill them.

This way of addressing the problem rejects the notion that there is a categorical difference between Homo sapiens and other animals with respect to their moral status. But it affirms a radical discontinuity between animals and other organisms such as plants and fungi. The latter do not feel pain, so it’s acceptable to take their lives

The empathic approach is far more sophisticated and plausible than the other two solutions to the problem of killing. It rejects the claim that hunted animals want to be killed and the supernatural paraphernalia accompanying it, and it also has no truck—at least explicitly—with the idea that living things are ranked on a moral hierarchy. But this approach doesn’t imply that it’s morally permissible to kill animals painlessly. Sentient beings have interests, and must be alive to pursue their interests. Preventing a being from pursuing its interests is wrong, so killing animals is wrong, even if the killing is painless.

The empathic solution is underpinned by what philosophers call moral realism, the view that there are facts about moral right and wrong. These facts are supposedly objective. They are independent of our judgments. Killing animals would be wrong even if nobody on earth believed it to be wrong.

This invites a question: “Why is causing animals to suffer, or make them unable to pursue their interests, morally wrong?” A common and attractive response is “It’s just wrong. That’s a fact. There’s no further justification required.” And to the question, “How do you know that it’s wrong?” the likely response is “My moral intuition tells me that it’s wrong.”

Moral anti-realists—people who reject the claim that there are moral facts3—can also disapprove of killing animals, but they don’t justify their disapproval by citing putative moral facts. Anti-realists can perfectly well say, “I think that killing animals is wrong because I don’t want to live in a world where animals are killed, and I do not want you to want to live in such a world either.”

Whatever their position on the morality of killing animals, anti-realists should take the realists’ intuitions seriously. They probably have the same intuition. The idea that suffering, or preventing a being from pursuing it’s interests exerts a very powerful pull on our hearts and minds, at least for certain sectors of the population. Anti-realists are not immune to this pull, but they can’t accept that intuitions that give us a hot line to moral truth.

The empathic approach is a normative ethical framework. It sets out a view of the attitude that we should have towards killing animals. But the nature of moral intuitions—their sources and mechanisms— is an empirical matter. So, the question of why killing animals seems intuitively wrong demands an empirical answer.

Here’s one possibility. Perhaps we feel that it is wrong to kill creatures that feel pain and have interests because feeling pain and having interests shows that other animals resemble us. I suffer and the pig suffers. The pig’s suffering is evidence that it resembles me. It’s wrong to kill human beings, so, derivatively, it’s wrong to kill pigs. And perhaps we are comfortable killing plants and fungi, not because they don’t feel pain, but rather because in not feeling pain they seem very different from ourselves.

Moral intuitions are as they are because an anthropocentric bias creeps through the mind’s back door. T. J. Kasperbauer summarizes some of the research in Subhuman: The Moral Psychology of Human Attitudes Towards Animals. For instance:

In an interesting experiment by Sarah Batt (2009), participants were presented with pictures of 40 different species and were asked to rank how much they liked each species in comparison to all the others. Batt also created a ranking of each species according to its biological similarity to humans (using a combination of behavioral, ecological, and anatomical information about each species). She then mapped people’s preferences for each species’ biological similarity to humans. The correlation between the two was moderately high…indicating that biological similarity did influence general preferences.

The problem of killing is at the heart of moral psychology, but has not been given the attention that it deserves. Maybe the problem has a solution, or maybe it is intractable, but understanding it is crucial for addressing our relations with other organisms as well the violence that we inflict on dehumanized human beings.

In his classic work The Great Chain of Being: A Study of the History of an Idea, Arthur O. Lovejoy argued that the Chain was a distinctively European idea derived from Greek philosophy, and that it died out by the early 19th century. I disagree. The idea of a cosmic hierarchy is considerably more ancient and widely distributed than Lovejoy claimed. And it has not disappeared.

It’s usually assumed that hums suffer more intensely than other animals, and that the simpler an animal is, the less pain its feels. That’s why some people who are loath to eat mammals have no problem consuming crustaceans. But it might be that this is wrong, and that the simpler the animal, the more pain it feels.

Full transparency: I’m a moral anti-realist.