Unmaking Race: Part One

A guide for the perplexed

This is the first of a series postings explaining my perspective on race—a position that I call race abolitionism. It is a position that I share with my spouse, the philosopher Subrena Smith, and a small but growing minority of thinkers scattered across several different disciplines.

A lot of our colleagues think that our position is strange, implausible, or offensive. We’ve been accused of playing “parlor games,” being confused, or sucking up to racist bigots. Obviously, we reject these accusations. So, I’ve decided to use this platform to set the record straight; to explain our position as clearly as possible, and to address the objections that are most commonly leveled against it.

But first a little background.

As readers of this newsletter are aware, I am a dehumanization scholar. And any dehumanization scholar worth their salt has got to address basic questions about race, because there is an intimate bond between the attitude that others are less than human and the belief that they belong to an alien and subordinate race. As I explain in my most recent book, groups of people are typically racialized—that is, believed to be and treated as an inferior, alien race—as a prelude to their dehumanization, I have been researching dehumanization for nearly two decades now, and in consequence have come to focus more and more on racial ideology and its horrific consequences.

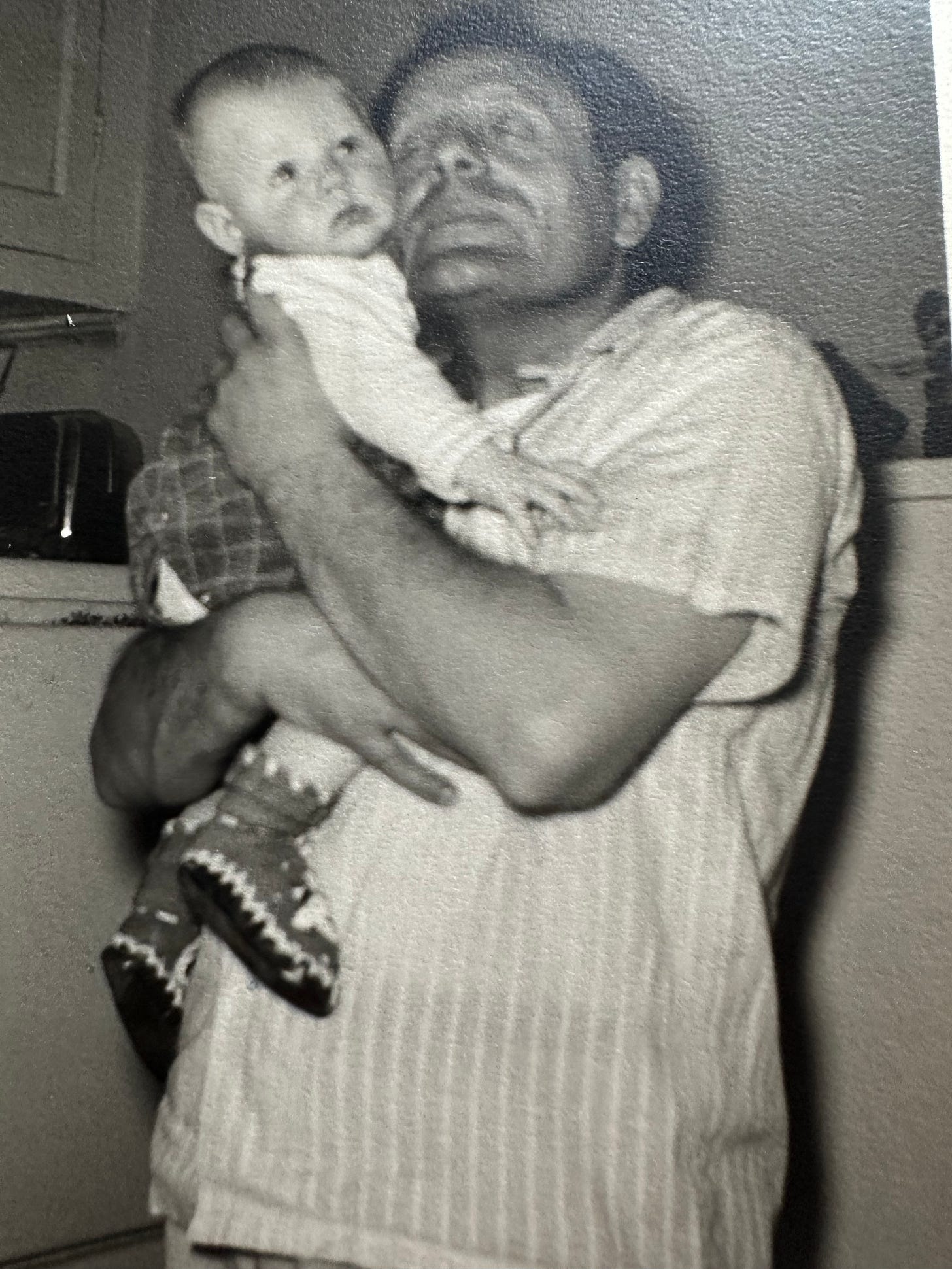

My engagement with race also has an autobiographical component. I grew up in the deep south in the 1950s and 60s. My family had moved from Brooklyn to Fort Myers, Florida, where where horrific racial oppression was a palpable. In fact, two African-American teenagers had been lynched there a little over thirty years before our arrival there.

Forget about subtleties such as dog-whistles or micro-aggressions; the anti-Black racism in small-town Florida was blatant, explicit, and utterly shameless—an everyday feature of everyday life.

My maternal grandparents, Bertha and Chiam (anglicized as Herman) were Jewish refugees from Eastern Europe. Both of them told stories of anti-Semitic violence. Even as a child, I was aware that these acts were racially motivated. My grandparents were non-observant atheists. My mother Rose was also a non-observant Jew, but nevertheless encountered overt, racial anti-Semitism in Florida (for example, she was told by an employer, “A Jew’s just a n*****r turned inside-out”).

My spouse, Subrena, is a philosopher of science. She was born and raised in Jamaica, and is a woman of unmistakably West African appearance. Growing up in Jamaica, race was not a salient category. Of course, people used terms like “Black” and “White,” but these labels were not burdened with the baggage that the same words carry in the US. They were mostly used as superficial descriptors—analogous to terms like “tall,” “short,” “blond,” and “brunette.”

Subrena often says, “I only became Black when I moved to the United States,” and then adds, in seeming contradiction, “I am not Black.” The seeming contradiction is resolved by a fuller explanation. A racial identity as “Black” was ascribed to Subrena when she came to this country, but she never subscribed to it. “Blackness” was not part of her identity—her sense of herself—and people’s insistence on attributing it to her felt, and continues to feel, like an assault on her humanity.

Race was not initially one of Subrena’s research interests. She is best known for her critique of evolutionary psychology and her work on the nature of organisms. However, the degree to which Americans are marinated in racial ideology rendered her turn to race all but inevitable.

I’ve boiled down the race abolitionist position into six main points.

Human races do not exist biologically. This is pretty uncontroversial among people who study race. “Race” just isn’t a meaningful biological category. The response that race must be real because some groups of people look different from others conflates race with biological variation. This is a mistake.

Races are “socially constructed,” but fictional. Most people who agree that race is not a biological reality assert that race is races are “socially constructed.” I use scare quotes here, because this expression is ambiguous. Sometimes social constructions are taken to be things that are brought into existence and sustained by social practices and beliefs. Money, marriage, and professions all fall into that category. But some social constructions are fictional. These are not brought into existence by social convention, and there is nothing in the world—the real world—corresponding to them. The “great replacement,” adrenochrome harvesting, angels, and Bigfoot are examples. As socially constructed fictions, races more like Bigfoot than they are like money.

Every statement attributing properties like “Whiteness” and “Blackness” to people is false. If races don’t exist either socially or biologically, racial properties don’t exist either. Filtering the world through such concepts sustains a distorted picture of reality.

Race is an ideology, by which I mean a system of beliefs, representations, and practices that has the function of oppressing others.1 Therefore….

Racism is real, even though race isn’t. Race abolitionism does not entail the denial or minimization of racism. Quite the opposite. To paraphrase Edouardo Bonilla-Silva, there is racism without race.

We should oppose racial categorization. We should destabilize it rather than affirm it. The ideological fiction of race is an evil, responsible for violence and injustice on a scale that beggars the imagination. And what good uses it has been put to—primarily, fostering solidarity among its victims—should be seen against this backdrop. The ideology of race has ravaged the world. The evil that it has wrought is staggering, and it behooves us all to take a stand against it.

Unless something more pressing occurs I’ll begin to unpack these points in my next posting. So, no matter whether you agree or not, if you’re interested, stay tuned.

For a detailed account, see Chapter 9 of my Making Monsters: The Uncanny Power of Dehumanization.

Excellent. Agree with every word.

I came across your idea from the "Philosophy or Our Times" podcast and became intrigued. Something I am trying to make sense of in this framework is how we make sense of the racialized experiences that are a fact of our history if we are to rid ourselves of the notion of race? Are we going to say that people with more melanin who live in Boston are more likely to be arrested than those with less melanin pigments in their skin? Surely racism can exist without race, but how do we rectify racism without referencing race (real or not). Ultimately, I'm curious about your thoughts on how we reconcile this framework with efforts of affirmative action?