What Should We Be Talking About When We Talk About Dehumanization?

Why dehumanization studies is such a hot mess

The field of dehumanization studies is a hot mess. Even a casual glance at the research literature reveals that the very same term—“dehumanization”—is used to characterize a very wide range of phenomena, stretching all the way from genocidal ideologies to motorists’ attitudes towards cyclists1.

This situation would be ludicrous if it wasn’t so grave. Dehumanization concerns human well-being, life and death, flourishing and oppression. History teaches that we neglect it at our peril.

I’m a philosopher, and I think that the discipline of philosophy can help us out of the morass of confusion that dehumanization studies is mired in. But to do that, we philosophers need to keep our eyes on the prize. We need to resist the temptation to play the sort of word games that are common and incentivized in academic philosophy, and avoid the trap of incessantly polishing our eyeglasses without ever putting them on.2

Since at least the time of Socrates, philosophical enquiry begins with the question “What the hell are we talking about?” The way that this question gets answered provides a conception of the thing that we are trying to understand.3 It’s only after settling on a reasonably clear conception of a thing under consideration we’re in a position to theorize it.

Theories are tools for explaining phenomena. It’s only when we know what we are talking about that we can try to identify its causes and effects. There’s an asymmetrical relationship between conceptions and theories. Any conception of a phenomenon is compatible with multiple theories of it. In other words, there’s always more than one way to try to explain anything. But no two (mutually exclusive) conceptions of a phenomenon share a single explanation. It’s pretty obvious why: two different kinds of phenomena can’t have identical kinds of causes and effects.

Once we decide what it is that we’re trying to explain (the conceptual dimension), and have identified some possible explanations for it (the theoretic dimension) we can proceed make observations to test those theoretical conjectures (the empirical dimension). Once again, there’s an asymmetrical relation between theory and data. As the philosopher Han Reichenbach4 famously pointed out, “Theories are underdetermined by data.” Any body of data is logically compatible with more than one theory, but it’s not the case that any theory is compatible with all possible observations. Theories place limits on how the world has to be in order for the theory to be true.

All too often, behavioral scientists don’t pay enough attention to conceptualizing and move too quickly to theorizing and empirical investigation. This is a significant problem when researchers have quite different and even incompatible notions of the thing that they are investigating. Under such circumstances, they are likely talk past one another, tacitly assuming that they are investigating different aspects of the same thing. Researchers may believe that they each have part of a larger, unitary truth—as in the Buddhist parable of the blind men and the elephant—when in fact they are addressing entirely different things.

This invites the question, “How do we choose between rival conceptions?” At the most basic level, one’s conception should do justice to paradigmatic examples of the phenomenon—examples that nearly everyone would consider an example of the thing under consideration. Suppose, for example, that a person (let’s call her Sara) is developing a conception of war, but her conception—her view of what war is—doesn’t apply to World War I. If anything was a war, World War I was, so Sara’s analysis of war is conceptually inadequate.

When I began researching dehumanization, nearly twenty years ago, almost all of the research into it had been done by social psychologists. I soon came to the conclusion that this work is both conceptually inadequate and theoretically flawed. In this posting I’m concerned with conceptual adequacy. I’ll address the theoretical problems further down the road.

There are three major social psychological conceptions dehumanization that dominate the literature. The most influential of these is Nick Haslam's “dual model.” Haslam, a psychologist at the University of Melbourne, conceives of dehumanization as regarding others as less human than oneself. This can take two forms. The dehumanized other is either thought to be machine-like (“mechanistic dehumanization”) or is thought to be animal-like (“animalistic dehumanization”).

Adam Waytz and Nicholas Epley's “mind perception model” has also been very influential. Waytz and Epley conceive of dehumanization as the failure to attribute mental states and processes to others. On their view, dehumanized people are seen as mentally impaired or, at the extreme, as mindless beings.

Finally, Susan Fiske and Lasana Harris’ “stereotype content model” conceives of dehumanization in terms of attributions of diminished interpersonal warmth and competence. Harris and Fiske say that their model “predicts that only extreme out-groups, groups that are both stereotypically hostile and stereotypically incompetent (low warmth, low competence), such as addicts and the homeless, will be dehumanized.”5

Now, let’s evaluate the adequacy of each of these three mainstream psychological accounts by asking (1) how well they comport with a paradigmatic example, and (2) how consistent they are with our best science (spoiler: the results are disappointing).

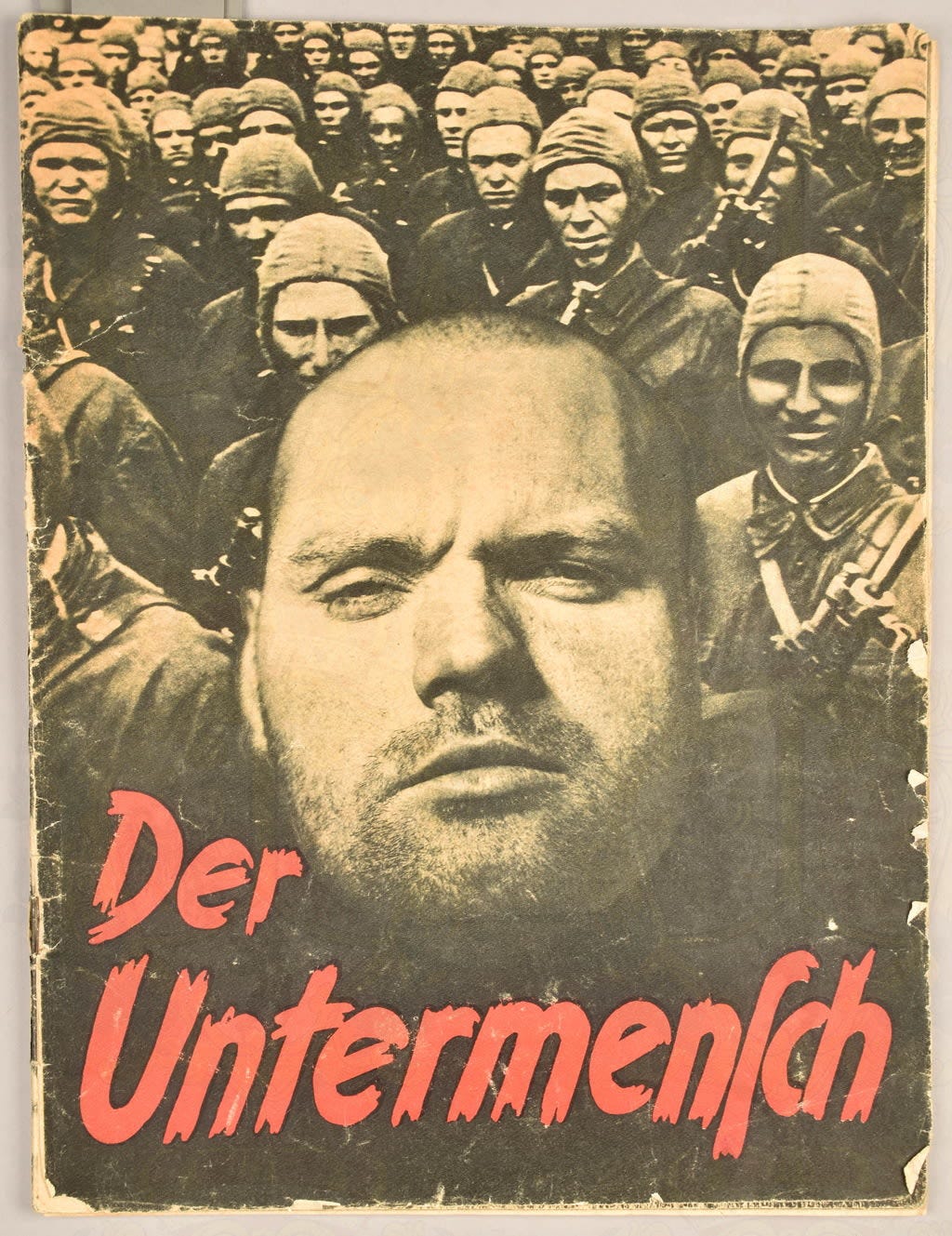

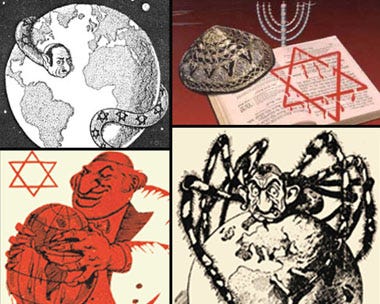

I doubt that any scholar working in this arena would deny that Nazi antisemitism is a paradigmatic example of dehumanization. But if we accept this, then Waytz and Epley's conception of dehumanization fails. Nazis did not believe that Jews are intellectually impaired. They thought of them as diabolically intelligent, and therefore as a formidable enemy. As Adolf Eichmann stated in an interview with Willem Sassan, Jews possess “the most cunning intellect of all the human intellects alive today” and are “intellectually superior to us.”6

As I’ve mentioned, Haslam proposes that there are two forms of dehumanization. We dehumanize others mechanistically when we think of them as lacking traits that distinguish animals from inanimate objects. We dehumanize them animalistically when we think of them as lacking traits that distinguish humans from other animals.

Nazis didn’t regard Jewish people as resembling inanimate objects, as “lacking emotion, warmth, desire, and vitality, and accordingly perceived as cold, inert, passive, and rigid…. as robotic or object-like: mere automatons or instruments.”7 They are represented in Nazi propaganda as sensuous, greedy, lustful beings.

What about animalistic dehumanization? According to Haslam, animalistically dehumanized people are thought to be “unintelligent, irrational, wild, amoral, unrefined, and coarse.8 Nazis often pictured Jews as wild, immoral and coarse, but not as unintelligent and irrational, and actually sometimes as overly refined cosmopolitans (and therefore as decadent). So, Haslam's model doesn’t do justice to Nazi antisemitism.

What about Fiske and Harris' account? According to them, dehumanized people are perceived as hostile and incompetent (low on warmth and low on competence).9 It’s true that Nazis saw Jews as hostile and destructive, but it would be absurd to think that Nazis saw them as incompetent. The Nazis believed that the world was being controlled by an international Jewish conspiracy. As Holocaust historian Jeffrey Herf writes, the Nazis believed that Jews “controlled the course of national and international events from the shadows of the wings…. Goebbels wrote that Germany had become ‘an exploitation colony of international Jewry,’ which controlled its railroads, economy, and currency.”10

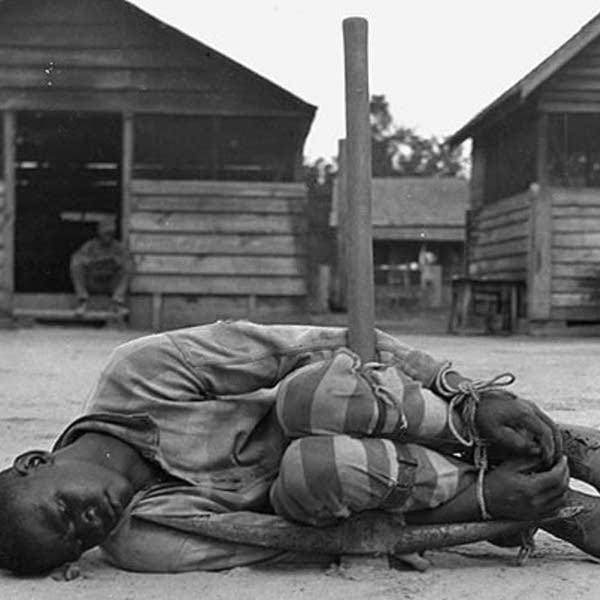

You might want to defend these three accounts by insisting that each of them does justice to a particular kind of example. Haslam’s notion of animalistic dehumanization accords with the dehumanization of Africans. Epley and Waytz’s account captures the dehumanization of cognitively disabled people. And Fiske and Harris’ model works with the dehumanization of homeless people. But to be conceptually adequate, a notion of dehumanization per se has got to apply to all paradigmatic examples, not just to one or a few. None of the existing social psychological accounts succeeds at doing that.11

I kid you not! See, for example, the article “How might advertising campaigns rehumanize” cyclists? https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Nick-Haslam/publication/382786122_How_might_advertising_campaigns_rehumanize_cyclists/links/66b1699d51aa0775f26bdda6/How-might-advertising-campaigns-rehumanize-cyclists.pdf

I owe this bon mot to Sigmund Freud, who used it to characterize those who fetishize methodological rigor.

This posting is largely based on my article “Some conceptual deficits of psychological models of dehumanization,” published in Current Research in Ecological and Social Psychology (Vol. 4, 2023), which can be accessed at https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2666622723000308

Some trivia for psychoanalysis mavens. Like several other logical empiricist philosophers, Reichenbach was deeply interested in psychoanalysis. After emigrating from Germany to the United States (via Instanbul University), he became a founding member of the Los Angeles Psychoanalytic Society.

This statement is not entirely transparent. On the one hand, Fiske seems to be offering a definition of dehumanization (i.e., a conception), but on the other she claims that her account predicts dehumanization, which is a theoretical claim (conceptions don’t “predict” anything). Put differently, it’s not clear whether she is saying that dehumanization is constituted by attributions of low warmth and low competence, or whether dehumanization is a causal consequence of such attributions.

This is quoted in Bettina Stagneth’s Eichmann Before Jerusalem: The Unexamined Life of a Mass Murderer, p. 304

Haslam et. al., (2006). “Dehumanization: an integrative review.” https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1207/s15327957pspr1003_4

Haslam et. al., (2006). “Dehumanization: an integrative review.” https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1207/s15327957pspr1003_4

Harris and Fiske (2006). “Dehumanizing the lowest of the low: neuroimaging responses to extreme outgroups.” https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1111/j.1467-9280.2006.01793.x

Herf (2008). The Jewish Enemy: Nazi Propaganda During World War II and the Holocaust, p. 37.

Alternatively, it might be that there is no unified phenomenon of dehumanization, and “dehumanization” is an umbrella term for a collection of rather different kinds of things. I don’t think that any of the psychologists that I’ve discussed would regard this sort of pluralism as an attractive option, nor would I.