Even people who don’t know much about Freud know that he believed that there is an unconscious part of the mind. Historians of psychology like to debunk Freud’s originality, claiming that the idea of the unconscious mind was commonplace. But pre-Freudian thinkers almost always meant something quite different by the term “unconscious mind” than Freud did. To understand this, we have to go back to Descartes’ influence on the development of psychology during the 19th century.

In my previous essay on Freud, I pointed out that he came to challenge the Cartesian view that body and mind are distinct—that the body is a physical thing and the mind is a non-physical thing—and opted for the view, which was quite radical at the time, that mental states are all states of a physical organ (the brain). It was around the same time, the spring of 1895, that Freud also rejected another core element of the Cartesian package, the view that the mind is transparent to itself. This “transparency thesis” was crucial to the early development of psychology as an empirical science. The first experimental psychologists took it for granted that the best way to investigate how the mind works is through introspection (literally, “looking inside”). Experimental subjects were trained to introspect, exposed to stimuli under laboratory conditions, and asked to report on what they noticed. Perhaps emulating the stunning scientific successes of the chemists and physicists, early psychologists such as Wilhelm Wundt wanted to discover the fundamental building-blocks—the “atoms”— of consciousness. But their hopes were dashed by wildly inconsistent results.

At around the same time, studies of the consequences of brain damage, experiments with hypnosis, and investigations of psychopathology suggested that human behavior can be influenced by unconscious cognition. But if mental states and processes are intrinsically conscious, how could this be? From the mainstream perspective, “unconscious mentation” seemed like an oxymoron. As neuroscientist John Hughlings Jackson wrote in 1887, “I take consciousness and mind to be synonymous terms….Unconscious states of mind are sometimes spoken of, which seems to me to involve a contradiction.”

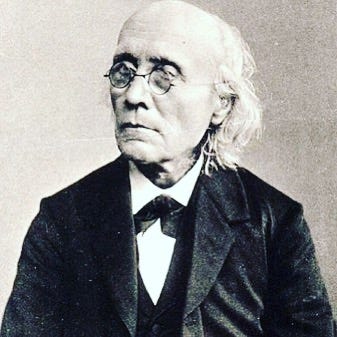

Researchers adopted two strategies for squaring these observations with the Cartesian legacy. One was to claim that the states are unconscious but not mental. Rather they were understood as neurological dispositions for behavior. For example, Gustav Fechner wrote:

Sensations, ideas, have of course, ceased actually to exist in the state of unconsciousness, insofar as we consider them apart from their substructure. Nevertheless something persists within us, i.e., the psychophysical activity of which they are a function, and which makes possible the reappearance of sensation, etc.

The other explanatory strategy was to accept that these states are mental but deny that they are unconscious. The idea here was that the conscious mind can be split into a main consciousness and one or more “sub” consciousnesses.1 Each of these multiple minds is conscious, but none of them has access to the mental states of the others. William James wrote in 1890,

How far this splitting up of the mind into separate consciousnesses may exist in each one of us is a problem…. An hysterical woman abandoned part of her consciousness because she is too weak nervously to hold it together. The abandoned part meanwhile may solidify into a secondary or sub-conscious self.

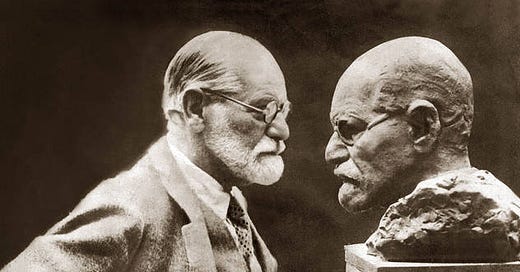

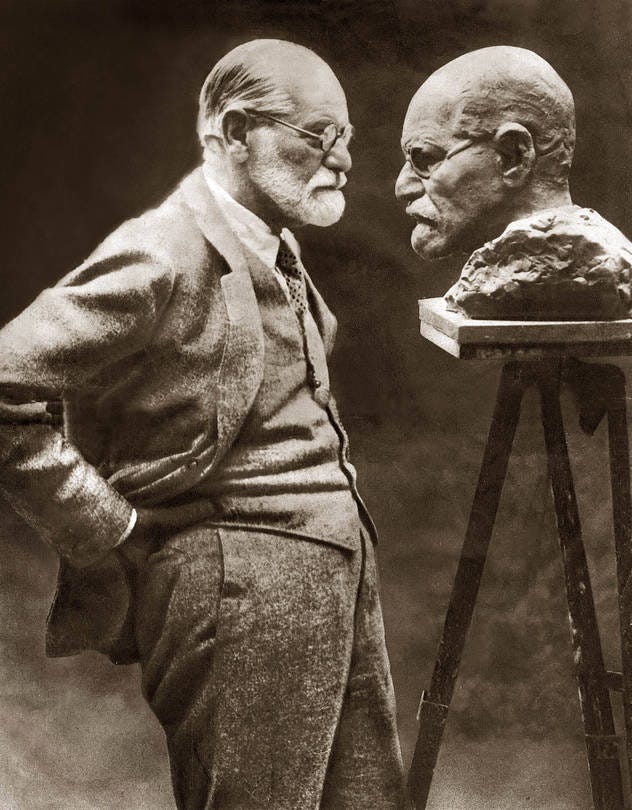

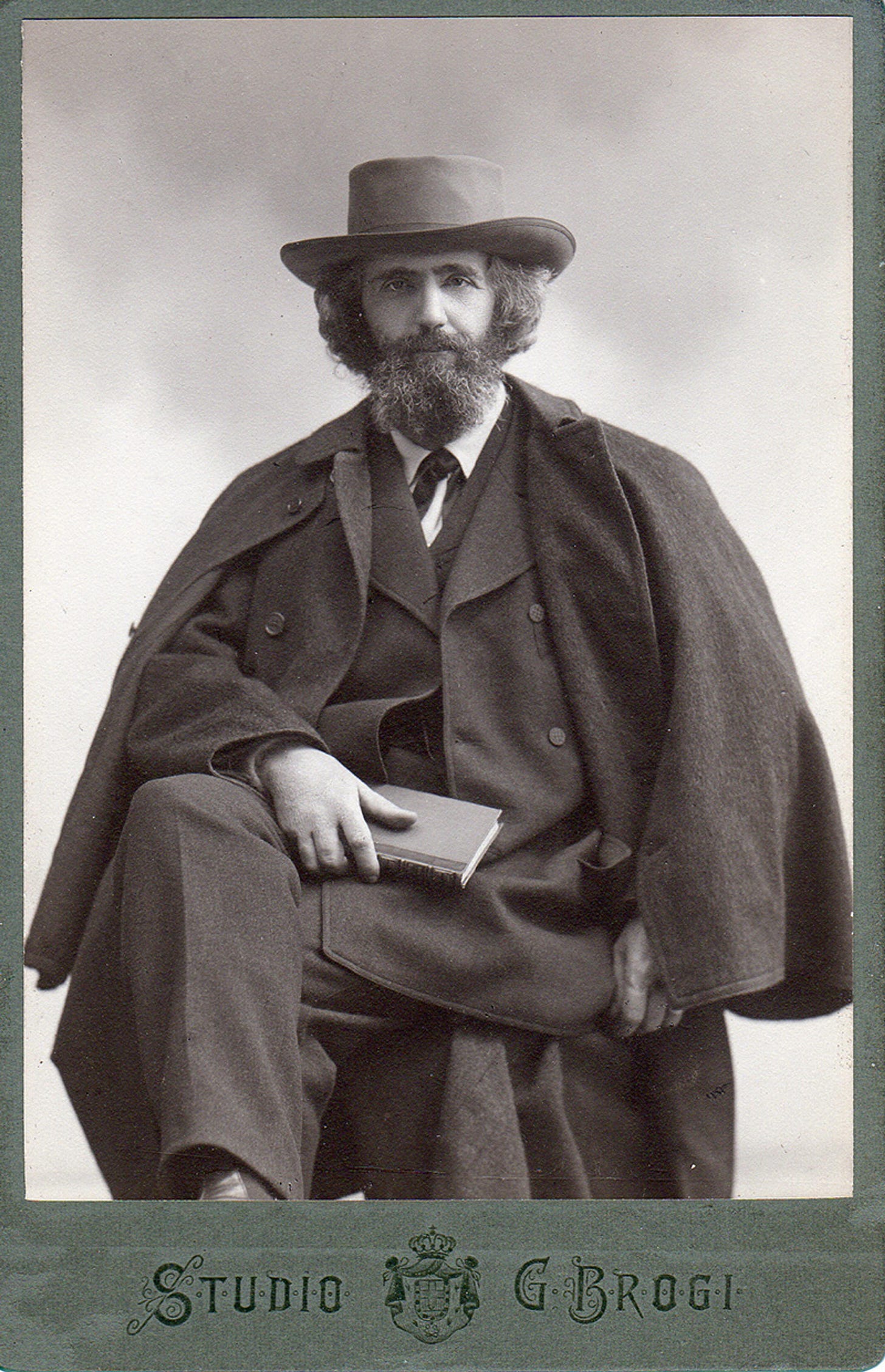

Freud had been exposed to both of these views as a student by his philosophy professor Franz Brentano, who wrote about them in his classic text Psychology from an Empirical Standpoint. Early in his career, Freud flirted with both approaches to ostensibly unconscious mental states, but in 1895—at the very moment that he shifted to the view that mental states are brain states as described in the manuscript titled “Project for a scientific psychology”—he rejected them both in favor of the much more radical view that genuinely cognitive processes can be genuinely unconscious.

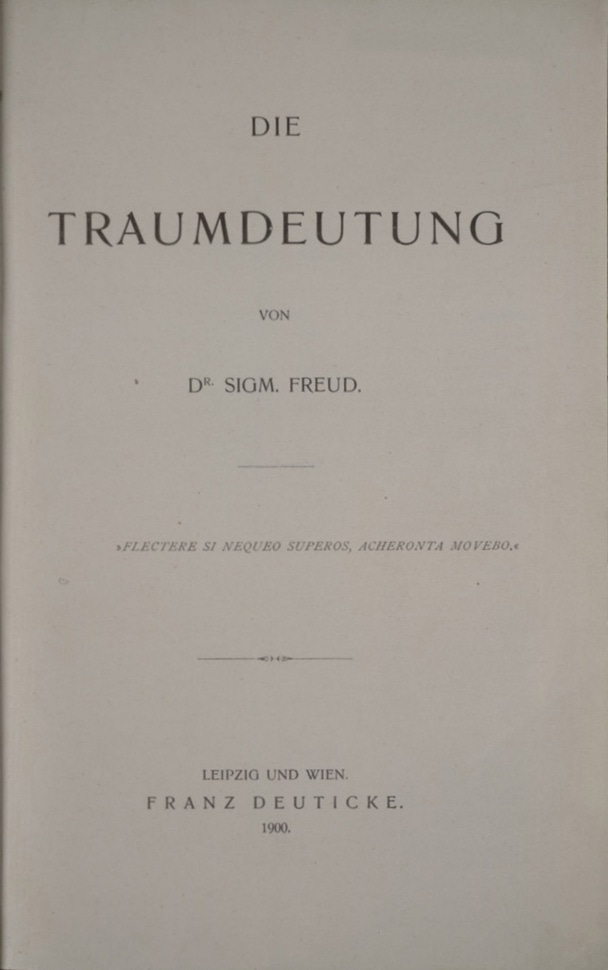

Freud’s settled position was even more radical than this characterization suggests. Most people with even a nodding acquaintance with Freudian thinking believe that Freud held that some of our thinking is conscious and that some is unconscious. But this isn’t correct. Freud came to believe that all cognitive processes occur unconsciously and therefore that there is no such thing as conscious thinking. Thinking never occurs consciously: so-called conscious cognition is the output of the mental processing going on behind the scenes. This is why Freud claimed in The Interpretation of Dreams that ‘the unconscious is the true psychical reality,” and remarked in other publications that “mental processes are in themselves unconscious.” Put a little differently, Freud thought that consciousness is the brain’s way of displaying itself to itself. If he were alive today, he might have used the analogy of a computer monitor, which displays the output of the computer but doesn’t do any of the processing.

If this sounds strange or even incomprehensible, let me ask you a question.

What’s your birthday?

As soon as you read this question, the answer popped into your head. This seems unremarkable. After all, it’s your birthday! But let’s look a little closer. What if I were to ask you how you did what you just did, how you pulled that information from your memory bank. The fact is, you don’t know! It was rather like doing a google search: typing a search term in the field, pressing the “enter” key, and seeing what pops up.

This is totally different from what often happens when we perform actions in the external world. You might be able to explain, step by step, how to make an omelet, cross-punch a heavy bag, build a tree-house, tie your shoelaces, or a million other things. But the processes that are most intimate, the processes within our own minds, are only indirectly accessible, if at all.

Psychologists, who also talk about unconscious mental processes, distance themselves from Freud by insisting that their “cognitive” notion of the unconscious is fundamentally different from Freud’s affective notion of the unconscious.2 But as I’ve explained, Freud’s notion of unconscious mental processing was entirely cognitive. In fact, he held that feelings—bodily sensations— are intrinsically conscious, and that there is no such thing as a repressed feeling.3

Freud avoided the term “subconscious” precisely because it was tied to this theory.

The term “cognitive unconscious” was coined by the developmental psychologist Jean Piaget, in a lecture that he gave to a group of psychoanalysts.

Freud thought that affects have two components: a state of physiological arousal, with accompanying sensations, and a cognitive component, which interprets those sensations. Only the cognitive component can be unconscious. So, one might be in an emotional state but be mistaken about the nature of that state.

Excellent discussion.