Pseudo-Philosophy

Caveat emptor!

There has been a sea-change in professional philosophy over the past decade or so. Philosophy has a reputation for being aloof from the concerns of non-philosophers, addressing at great length, using esoteric language, and in excruciating detail, topics that only philosophers care about (or at least, pretend to care about).

But times have changed. Philosophers are more and more willing to leave the seminar room for the street, communicating their thoughts about topics that matter to non-specialists in ways that non-specialists can understand, via accessible media such as YouTube and Substack in a movement called “public philosophy.” Goodbye esoterica. Hello relevance.

I think that this change is long overdue, and I applaud it. But it also has an evil twin. The internet has created a space for work that has all of the trappings of philosophy but none of its methodological rigor or substance. I call it pseudo-philosophy.

Pseudo-philosophy looks just like philosophy to people with little or no education in real philosophy. But in reality it is the very opposite. It is intellectually and morally corrupt, and very, very seductive.

So, what is pseudo-philosophy?

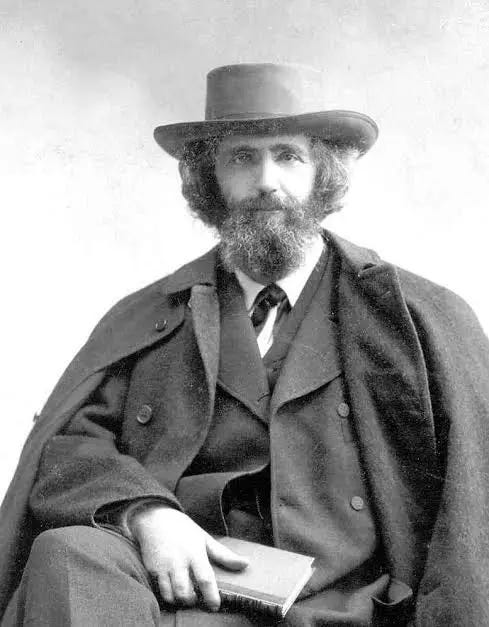

The term is modeled on “pseudo-science,” which was a key concept in the work of the influential philosopher of science Karl Popper, from which it entered the vernacular. Popper was interested in what’s called the “demarcation problem”—the problem of distinguishing science from other sorts of activities. The scalpel that he used to make this conceptual cut was the principle of falsifiability.

Popper’s idea is easy to understand. What makes a claim scientific is not its truth. Looking back at the history of science, there’s no shortage of claims that turned out to be false, but are nonetheless scientific. If truth were the criterion for science, then Newtonian physics (to name just one) wouldn’t count as science.

Science is defined methodologically. To count as scientific, a claim has got to be testable. And for Popper, testability boils down to falsifiability—the possibility of a conjecture being false. Popper argued that science isn’t in the proof business, its in the disproof business. He argued that we shouldn’t say that conjectures that survive testing are “proven” or “true”—only that they are corroborated.

Some systems of thought have all the trappings of science but none of the substance. It’s these that he labeled pseudo-science.

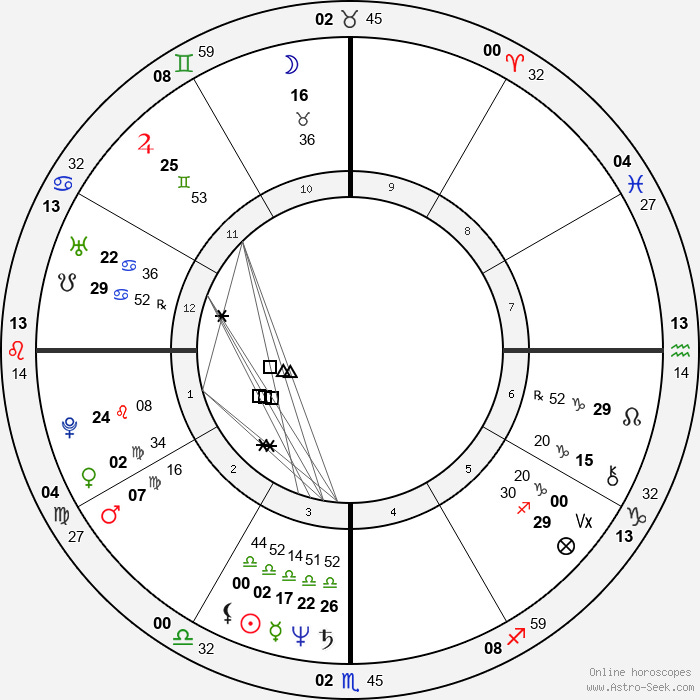

Popper offered three main examples of pseudoscience—astrology, Marxism, and psychoanalysis. I practiced astrology in my teens and early twenties, so I have an insiders’ perspective. It certainly seemed scientific to me, as well as others who took it seriously. But it isn’t science. The rules for interpreting horoscopes are vague and can’t be tested because there’s always plenty of wriggle-room for explaining away inaccuracies.

So, what’s pseudo-philosophy?

It’s not the same as bad philosophy or philosophy that one disapproves of. Ever since Socrates, philosophers have not been coy about disparaging those with whom they disagree. The seventeen-year-old Sigmund Freud, then a student at the University of Vienna, wrote to a friend about a meeting with his philosophy professor Franz Brentano. In it, he described how Brentano trashed members of the philosophical pantheon as intellectual crooks. The letter makes for hilarious reading.

Spinoza indulged in pure sophisms, he was to be trusted least of all…. Kant…did not deserve the great reputation that he enjoys; he was full of sophisms and was an intolerable pedant, childishly delighted whenever he could divide anything into three or four parts, which explains the inventions and fictions in his schemata….[W]hat makes Kant important is his successors, Shelling, Fichte, and Hegel, whom Brentano dismisses as swindlers.

He continued:

“And so you want to let us off reading them?” I asked. [Brentano replied] More than that, I want to warn you against reading them; do not set out on these slippery paths of reason—you might fare like doctors at insane asylums, who start out thinking people there are quite mad, but later get used to it and not infrequently pick up a bit of dottiness themselves.1

Brentano may have thought that Spinoza, Hegel, and the rest were pseudo-philosophers, but I doubt it. It’s more likely that he considered these men’s work as seriously flawed, but as genuinely philosophical (although I admit that the remarks about “sophisms” and “swindlers” might support a different interpretation). Brentano thought that these guys did bad philosophy, but he didn’t claim that they were mere simulacra of philosophers.

For the purpose of this essay, I reserve the term “pseudo-philosophy” for fake philosophers circulating their views in the public sphere. Many of them are YouTubers with massive followings. Just as pseudo-science isn’t the same as false science, pseudo-philosophy isn’t the same as false philosophy. Having a degree in philosophy is no guarantee that an internet guru isn’t a pseudo-philosopher (there are pseudo-philosophers with PhDs in philosophy from reputable universities) and, conversely, there are people who philosophize competently without the benefit of an academic qualification in philosophy.

At bottom, pseudo-philosophers are bullshitters, in Harry Frankfurt’s sense of the term. Frankfurt distinguishes bullshitters from liars. He regards the former as more corrosive and dangerous than the latter. Liars have got to keep an eye on the truth, because they’ve got to avoid it. But truth is irrelevant to bullshitters, whose discourse is an exercise in impression-management.

Of course, bullshitters claim to pursue truth, and claim to possess it. But that’s just more bullshit. It’s bullshit because pseudo-philosophers don’t honor the methodological core of genuine philosophy: intellectual humility that demands that one be open to objections, and appeals to logic and evidence to justify or question one’s claims.

Luckily for us, Chris Kavanaugh (an anthropologist) and Matt Brown (a psychologist) have compiled a checklist that they call the guruometer. Using the guruometer, Brown and Kavanaugh assign a “guruness” score to various internet personalities (they use “guru” in a pejorative sense). SThe following list is strongly influenced by their analysis.

Pseudo-philosophers promise salvation. Both individuals and the world as a whole will be redeemed by taking their message to heart. They further their ends by exploiting human unhappiness and insecurity.

Pseudo-philosophers are prone to self-aggrandizement. They make grandiose claims, tout their unique perspective, and boast about their influence and the size of their audience, and flatter their audience as an enlightened elite.

Pseudo-philosophers are cultish. They are adept at emotional manipulation and cultivate parasocial relationships with their followers, giving the false impression of friendship or intimacy.

Pseudo-philosophers are more interested in assertion than argumentation. They make striking claims, without setting out their logical and evidential justification.

Pseudo-philosophers have “galaxy brains.” They pretend to knowledge that they do not possess, exaggerate their own accomplishments, are dismissive of genuine expertise, and avoid interactions with real philosophers who might challenge them.

Pseudo-philosophers are disruptive. They disparage the mainstream as wrong or limited, and denigrate established knowledge. They present their ideas as revolutionary, as initiating an epoch-making paradigm.

Pseudo-philosophers play a special kind of language game. Their discourse is easy to process and gives the impression of profundity, but on closer inspection is trite, meaningless, contradictory or tautological. They name-drop to give the impression of erudition.

Pseudo-philosophers are mercenary. They have something to sell—merch, memberships, etc.

This list isn’t comprehensive, but it’s good enough for practical purposes. I plan to use it next semester in my Introduction to Philosophy to show students who are new to philosophy that not everything that looks like philosophy is philosophy. Caveat emptor!

My Substack newsletter is free, because most of the topics that I write about are too urgent to hide behind a paywall. If you think that my work is worth supporting, and want to help support it, I am grateful for paid subscriptions.

According to Freud’s letter, the philosophers that Brentano recommended were Descartes Comte, Locke, Leibniz, and Hume.

David, for those of us who are not professional philosophers, please define, describe, and/or enumerate the criteria for genuine or credible philosophy, as you did for genuine science vs pseudoscience.

Thank you.

I was expecting a few examples of this phenomena.